The Udine Far East Film Festival returns for its 24th edition 22nd – 30th April in a hybrid format with the complete programme screening at the Teatro Nuovo Giovanni da Udine and a selection also available to stream online in Italy and in many cases beyond (geographical restrictions noted below). While most films are available to stream for the entire festival, those marked “Gala” stream once only with a four hour window to view. This year’s recipient of the Golden Mulberry Award for Lifetime Achievement is Takeshi Kitano whose 1993 film Sonatine screens in the Restored Classics strand.

Cambodia

- White Building – A young man contemplates the loss of home and history as the building he’s lived in all his life faces demolition in Kavich Neang’s ethereal coming-of-age drama. Review.

China

- Hi, Mom – a young woman is transported back to 1981 and gets to know her mother as a young woman in a comedy directed by and starring comedian Jia Ling.

- I Am What I Am – CGI animation revolving around three village boys trying to master the traditional lion dance.

- The Italian Recipe – romance in which a spoilt pop star travels to Rome for a reality show and falls for a girl who wants to become a chef.

- Manchurian Tiger – black comedy starring Zhang Yu in which a truck driver, his wife, his girlfriend, and a poet recovering from mental illness are caught up in a bizarre series of events. Online Italy only.

- Nice View – dramedy from Wen Muye (Dying to Survive) in which a young man takes a chance on a risky business venture to pay for his sister’s medical treatment.

- Return to Dust – rural romance in which a couple who met through an arranged marriage come to trust and respect one another.

- Too Cool to Kill – Chinese remake of Koki Mitani’s movie set comedy The Magic Hour. Online Italy Only

- Streetwise – gritty drama in which a 21-year-old man becomes a debt collector to pay his father’s medical bills.

Hong Kong

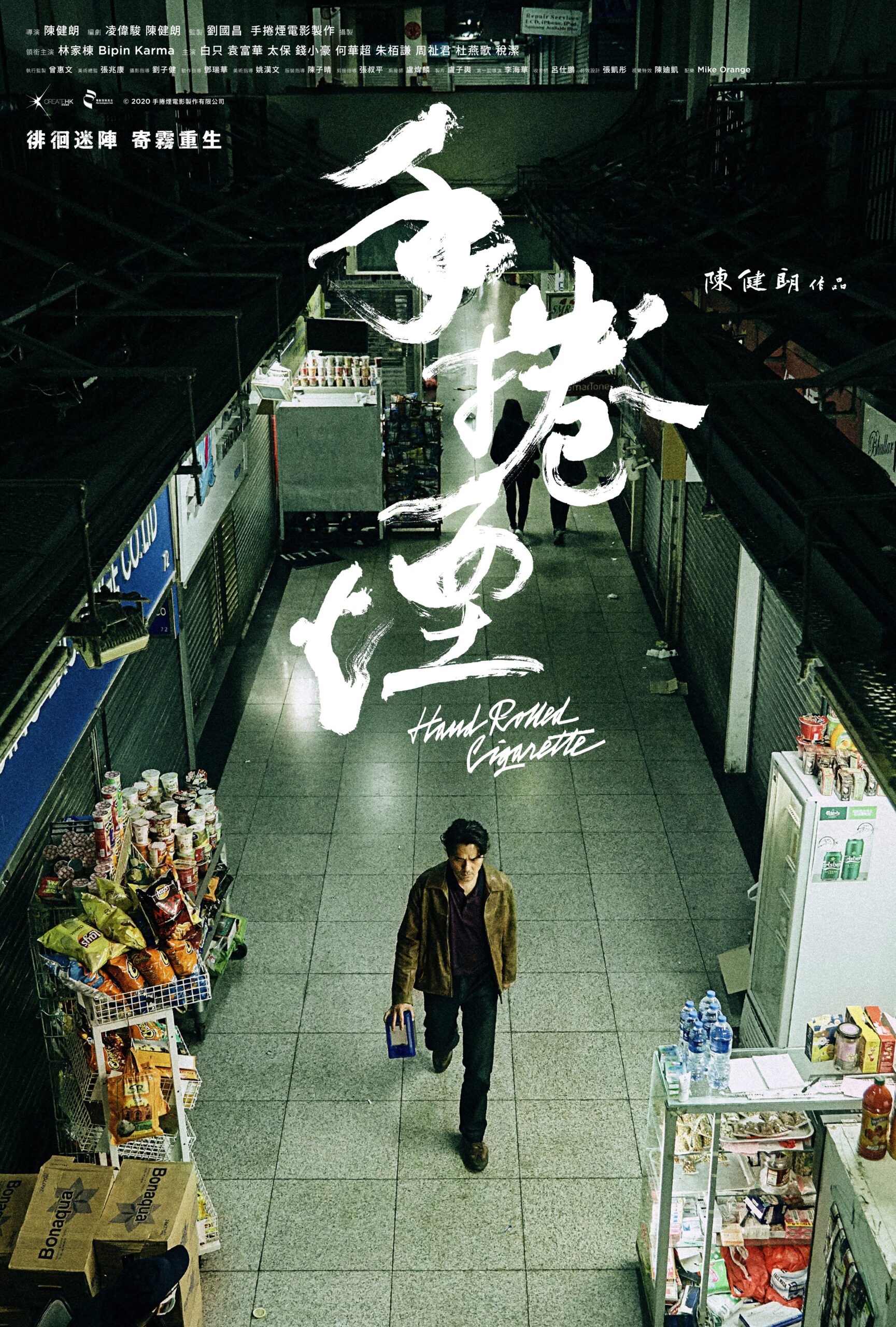

- Caught in Time – crime drama inspired by real life criminal Zhang Jun. Online Italy Only

- Far Far Away – An introverted IT guy (Kaki Sham) gets a crash course in romance when he ends up dating a series of women from the far flung corners of Hong Kong in Amos Why’s charming romantic comedy. Review.

- The First Girl I Loved – A young woman begins to re-evaluate her teenage romance when her first love asks her to be maid of honour at her wedding in Yeung Chiu-Hoi & Candy Ng Wing-Shan’s youth nostalgia romance. Review. Online Worldwide (Except Asia)

- Legendary in Action! – wuxia from Justin Cheung.

- Schemes in Antiques – mystery adventure from Derek Kwok in which a drunken antiques expert must find a priceless Buddhist head. Online Italy Only.

- Table for Six – anarchic comedy from Men on the Dragon’s Sunny Chan in which a crisis erupts at a family dinner when one of the guests arrives with the host’s old flame.

- Tales from the Occult – horror anthology featuring entries from Fruit Chan, Fung Chih-chiang, and Wesley Hoi

- Twelve Days – marital drama starring Stephy Tang and Edward Ma

- Sunshine of My Life – autobiographical drama about the sometimes difficult relationship between a daughter and her parents each of whom are blind.

Indonesia

- Yuni – A young woman decides she wants more out of life but finds herself trapped by the oppressive social codes of her conservative hometown in Kamila Andini’s bleak social drama. Review. Online Italy Only

Japan

- Just Remembering – bittersweet love story from Daigo Matsui inspired by Jim Jarmusch’s Night on Earth.

- Love Nonetheless – erotic comedy from Jojo Hideo. Online Worldwide.

- Missing – darkly comic thriller in which a young girl searches for her father who went missing after saying he was going to claim the bounty on a serial killer he spotted in town.

- My Small Land – a young woman who came to Japan as refugee when she was a child finds her life upended when her family’s refugee status is revoked.

- Noise – drama from Ryuichi Hiroki in which three childhood friends attempt to cover up a murder. Online Europe Only.

- One Day, You Will Reach the Sea – powerful drama from Ryutaro Nakagawa in which a young woman struggles to come to terms with the loss of a friend who went missing in the 2011 tsunami. Online Italy Only

- Popran – outlandish comedy from Shinichiro Ueda in which an arrogant CEO’s genitals decide to leave him and he has to find them within six days or lose them forever. Online Italy only [Gala]

- What to Do with the Dead Kaiju? – satire from Satoshi Miki in which bureaucrats must try to decide how to dispose of the corpse of a defeated kaiju.

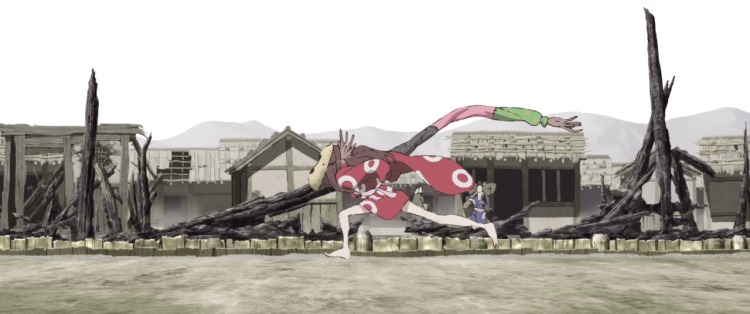

- INU-OH – a blind Biwa player and a cursed young man exorcise the spirits of the Heike through musical expression in Masaaki Yuasa’s stunning prog rock anime. Review.

Malaysia

- The Assistant – thriller in which a man unjustly imprisoned plots revenge

- The Devil’s Deception – horror in which a pregnant woman haunted by her brother’s death begins to have strange visions while staying at a remote mansion

The Philippines

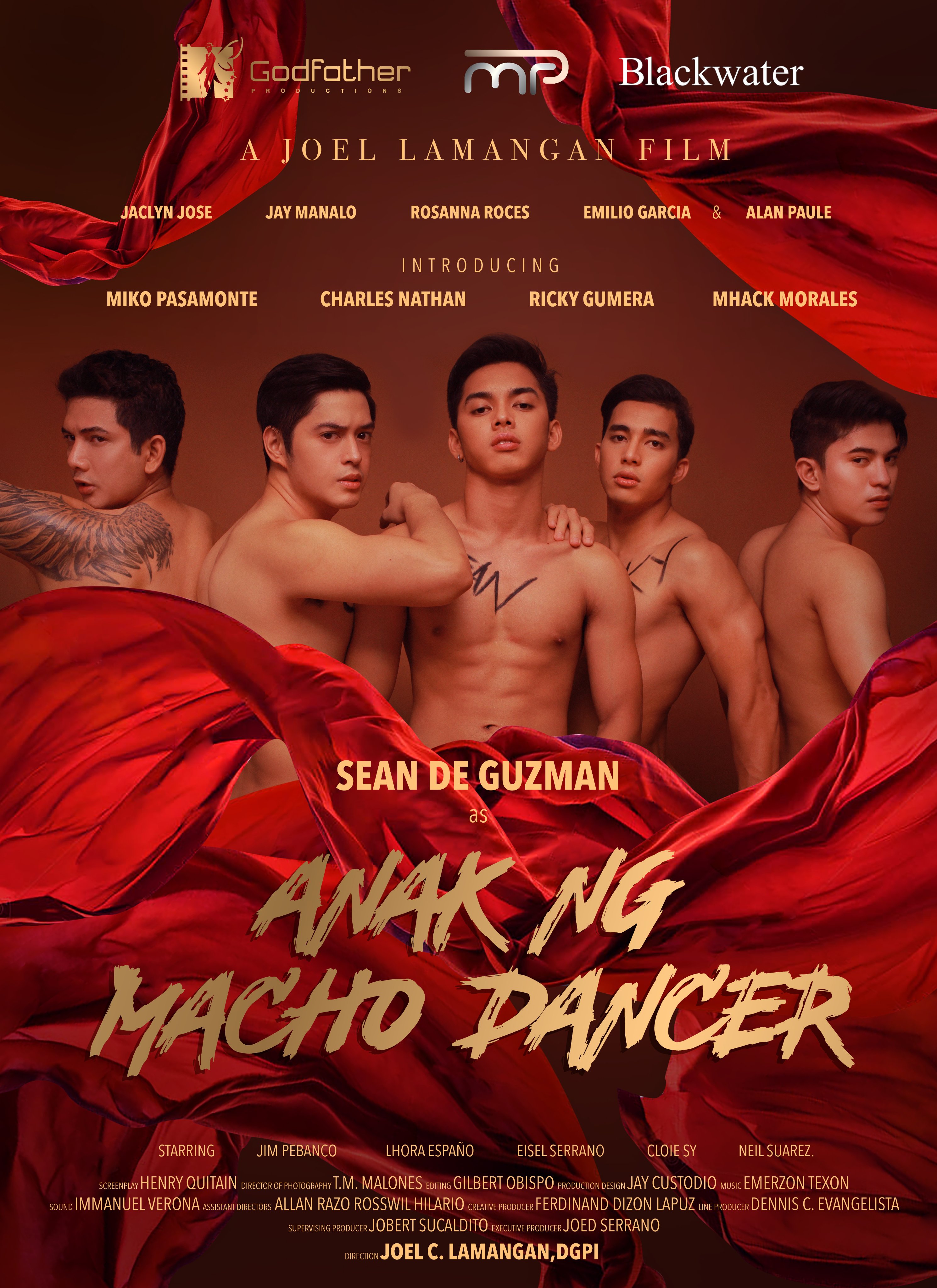

- Leonor Will Never Die – cineliterate meta comedy in which a formerly successful filmmaker now struggling to make ends meet is thrown into an unfinished script after being knocked out by a TV set. Online Italy Only [Gala]

- Rabid – pandemic-era horror anthology from Erik Matti. Online Worldwide.

- Reroute – horror in which a couple end up in a sinister place when their car breaks down while taking the scenic route home. Online Worldwide.

- On the Job: The Missing 8 – sequel to On the Job in which a corrupt reporter begins an investigation when his colleagues disappear while a hitman imprisoned for a crime he didn’t commit plots escape.

South Korea

- The Apartment with Two Women – familial drama in which the already strained relationship between a mother and daughter declines when one runs the other over.

- Confession – mystery drama in which a man is accused of a locked room murder

- Hostage: Missing Celebrity – remake of Saving Mr Wu in which actor Hwang Jung-min is kidnapped and must try to escape. Online Worldwide.

- The Killer – a former hitman is charged with babysitting a friend’s daughter only for her to be kidnapped by thugs

- Kingmaker – political drama revolving around an idealistic politician and his campaign strategists. Online Italy Only

- Miracle: Letters to the President – ’80s-set drama in which a small rural town comes together to build a railway station

- Perhaps Love – romantic drama in which a blocked writer bonds with an aspiring author. Online Worldwide

- Special Delivery – action drama starring Park So-dam as a delivery driver who is drawn into intrigue when a child gets into her car. Online Worldwide.

- Thunderbird – a taxi driver tries to get back a car his brother pawned which is filled with his gambling winnings but nothing goes to plan.

- Tomb of the River – gangster drama in which rival gangs go to war over the building of a lucrative resort. Online Worldwide [Gala]

- Escape from Mogadishu – North & South Korean diplomats are forced to set ideology aside to escape the increasing violence of the Somali Civil War in Ryoo Seung-wan’s intense action drama. Review.

Taiwan

- Incantation – interactive found footage horror movie in which a mother tries to cure her daughter of a curse

- Mama Boy – romantic drama in which a young man falls for a single mother working at a love hotel

- Terrorizers – drama revolving around an angry young man who goes on a public slashing attack

Thailand

- Cracked– horror in which a prominent painter’s suicide provokes a series of bizarre events. Online Worldwide.

- One for the Road – a New York club owner returns to Thailand on learning that his friend has been diagnosed with terminal cancer. Online Italy Only.

Documentaries

- Citizen K – Yves Montmayeur’s documentary exploring the career of Takeshi Kitano. Online Worldwide

- Fanatic – documentary focussing on former fans of idols accused of crimes

- Finding Bliss: Fire and Ice – The Directors’ Cut – actors, musicians and artists from Hong Kong go on an Icelandic roadtrip. Online Worldwide

- Kim Jong-boon of Wangshimni – documentary focussing on an ageing Korean street vendor whose daughter was killed during a protest. Online Europe

- Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist – Pascal-Alex Vincent paints an enigmatic picture of the late Perfect Blue director. Review. Online Italy only.

Restored Classics

- Audition – Takashi Miike’s deceptive drama begins as a gentle romcom before edging slowly towards the horrific as a widower (Ryo Ishibashi) takes his his friend’s advice and sets up a fake audition to find the perfect wife but ends up finding something quite different.

- Battle Royale Director’s Cut – Kinji Fukasaku’s millennial classic in which a class of school children is sent to an island and forced to fight to the death

- The Heroic Trio – Anita Mui, Maggie Cheung, and Michelle Yo star in Johnnie To’s 1993 classic

- Executioners – sequel to Heroic Trio

- Initial D – Andrew Lau & Alan Mak’s 2005 adaptation of the Japanese drag race manga

- The Swordsman of All Swordsmen – Joseph Kuo’s 1968 wuxia following a swordsman’s 20-year quest to avenge the death of his parents

- Pale Flower – Masahiro Shinoda’s 1964 noir starring Ryo Ikebe as a recently released yakuza drawn to a self-destructive female gambler

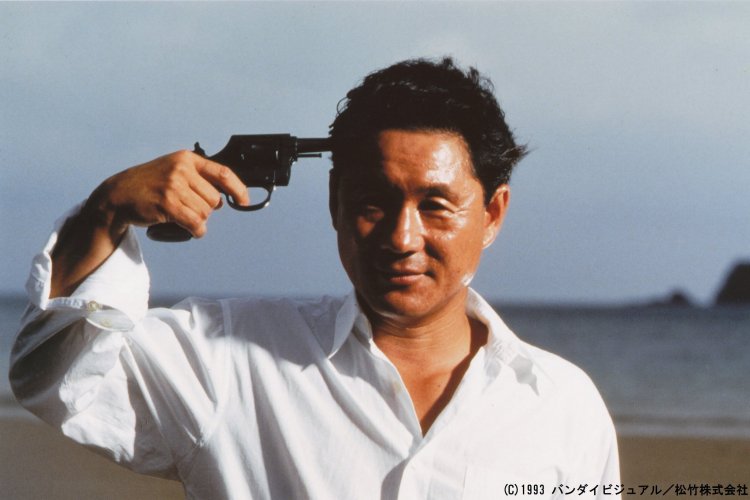

- Sonatine – Tired of the life, a veteran gangster ponders retirement but knows his brief island holiday is only a temporary respite from his nihilistic life of violence in Takeshi Kitano’s 1993 melancholy existential drama. Review.

Visions of Manila in Philippines Movies

- Manila by Night – Ishmael Bernal’s 1980 oddyssey through the nighttime city. Online Worldwide [Gala]

- Manila in the Claws of Light – Lino Brocka’s 1973 drama in which a young man travels to the city in search of his missing girlfriend. Review.

- Metro Manila – Sean Ellis’ 2013 social drama in which a man moves to the city and becomes an armoured truck driver. Online Italy only

- Slingshot – Brillante Mendoza’s 2007 neo-realist noir. Online worldwide

- Neomanila – Mikhail Red’s 2017 bleak extra judicial killing drama. Review. Online Worldwide.

The 24th Udine Far East Film Festival runs online and in person at the Teatro Nuovo Giovanni da Udine 22nd – 30th April. Full details for all the films are available via the official website and you can keep up with all the latest news by following the festival on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, Twitter, and Tumblr.