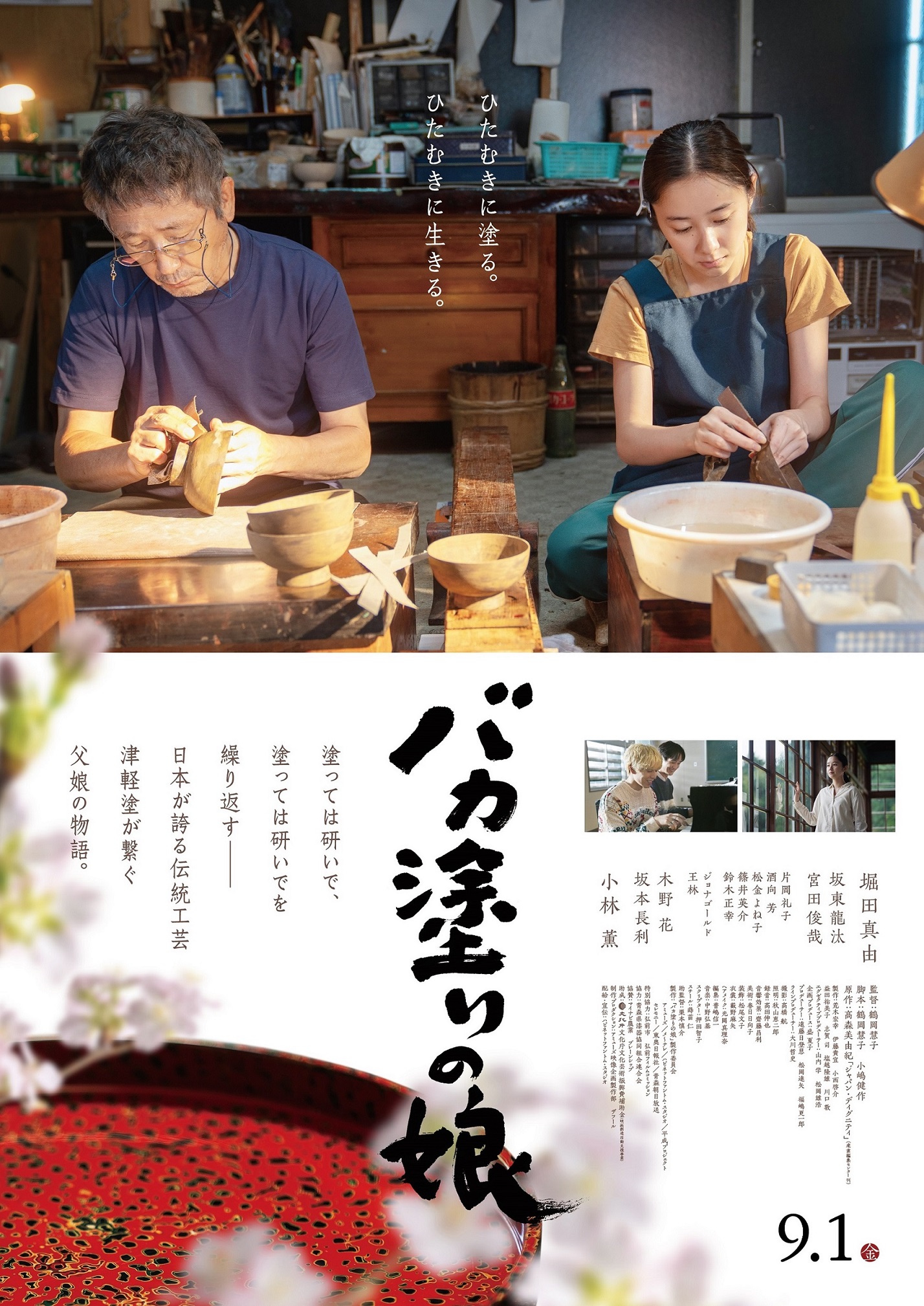

Which traditions should we keep and which should we lose? A young woman finds herself frustrated by outdated gender norms in her desire to take over the family lacquerware business in Keiko Tsuruoka’s gentle rural drama, Tsugaru Lacquer Girl (バカ塗りの娘, Bakanuri no Musume). While her family, save older brother Yu (Ryota Bando) who has already rejected lacquerware, do nothing but run her down and claim she’ll never be a success at anything all she wants to do is devote her life to a traditional craft her father no longer believes has any kind of future.

Even so, Seishiro (Kaoru Kobayashi) is dead set on Yu taking over the business to the point that they have become semi-estranged. He calls Miyako (Mayu Hotta) “clumsy” and complains that she has no aptitude for anything unlike Yu who was always good at anything he tried. Miyako too later suggests that she was her brother’s opposite, while he was cheerful and outgoing she is shy and melancholy but then perhaps it’s hard to be cheerful when everyone’s always telling you you’re useless and doing everything wrong. In an interesting parallel, Yu is also trapped by outdated social codes in that he is gay and he and his partner have decided to move to London where they can legally get married and live their life out and proud in a way they feel they cannot do in contemporary Japan.

Lacking other direction in her life, Miyako has been working a part-time job in a local supermarket which she hates while her father occasionally allows her to help him finish big orders though it’s clear her salary is now their main source of financial support. A local inn keeper who is a good customer of theirs explains to some of his guests that craftsmen rarely construct large pieces such as tables because they are no longer cost effective while fewer young people are willing to take up apprenticeships leaving the traditional art in danger of dying out despite the frequent remarks that everything tastes better out of a lacquerware bowl which is after all in the modern parlance “sustainable” in that it will last for many decades and can easily be repaired if damaged.

Seishiro doesn’t seem to have a reason for rejecting the idea that Miyako might take over aside from basic sexism in preferring to hand the business over to his first born son. It might be tempting to think that he dissuades her because he thinks there isn’t a future in lacquerware, but if that were the case he could simply retire. Her mother (Reiko Kataoka), who left the family some years ago in part it seems because of her own animosity towards lacquerware and its lack of financial promise, seems to feel much the same comparing Miyako to a more successful cousin who has kids and a high powered job at an international trading firm, telling her that she should be settling down and getting married suggesting that she is simply incapable of becoming a successful lacquerware artist and should at best keep it as a hobby.

Her mother had also shut down her desire to learn piano as a child by telling her there was no point because she’d never be good at it. Miyako’s decision to prove herself by re-laquering an abandoned piano in her disused school is then an act of rebellion against both parents showing them what she can and will achieve along with the direction she has chosen for her life. Not everyone respects it even if her father begins to come around but really it doesn’t matter because the decision is hers alone whatever anyone else might have said. Far from being insular, the embrace of traditional culture gives Miyako new opportunities and allows her to grow in confidence until she’s finally ready to set off along her own path. Even so, it seems there are some traditions she thinks it would be better to lose, such as her father’s sexism and the homophobia that has forced her brother to emigrate in order to live a happy life just as he is. They call it “fools lacquer” because no one but a fool would go to all this trouble to make a bowl but in many ways that’s the point. Miyako pours all of herself in to the lacquer, piling layer on layer dotted by handfuls of thrown rice that give it its pattern much as she herself is slowly tempered by the world around her.

Tsugaru Lacquer Girl screened as part of this year’s Camera Japan.

Original trailer (English subtitles)