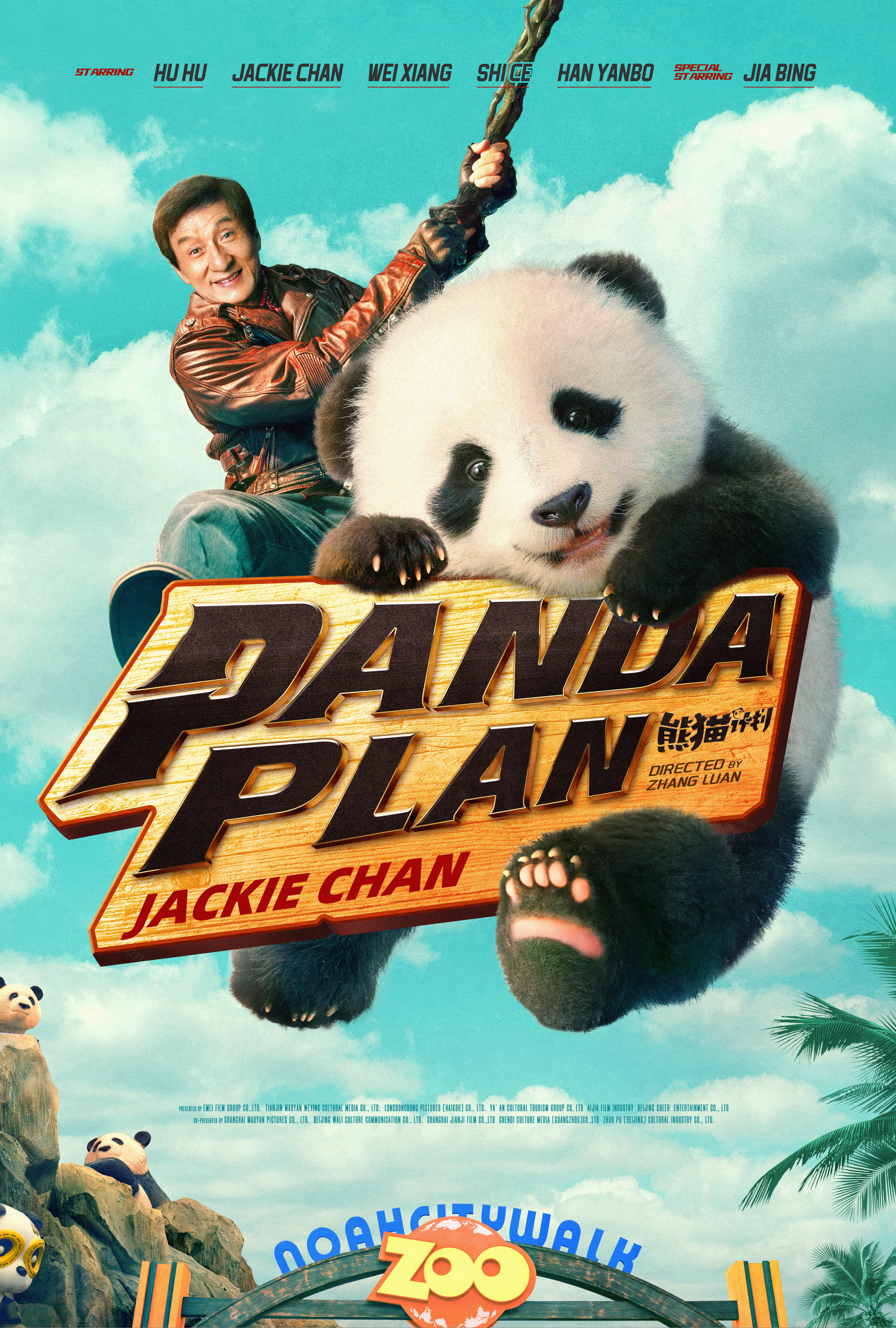

Now 70 years old, Jackie Chan’s later career has mostly seen him trying to find ways to mitigate his age. Often he’s played the role of a mentor figure taking part in a limited number of action scenes while a younger actor does the heavy lifting and takes care of any romantic subplots. Rest assured, there’s no romance in Panda Plan (熊猫计划, xióngmāo jìhuà) but it does otherwise see Chan trying to recapture past glory in seemingly appearing in lengthier action scenes while playing a version of himself.

As the film’s Jackie, he tells young panda nanny Zhuzhu (Shi Ce) that the reason he can’t bring himself to retire is that as soon as someone shouts “action” he can be an all powerful hero rather than a flawed human being that gets sad or tired or beaten down. He even pokes fun at himself with an early scene of Jackie shooting a movie and challenging the director that it’s unrealistic for him to take out all these bad guys all on his own. Though he is apparently sick of doing action, all of the directors future ideas for him sound like they will once again involve quite a lot of fighting.

It is then a bit ironic that Panda Plan’s action scenes are often choppily edited because it’s obvious that they’re cutting back and fore between Chan and a stunt double with quite a lot of CGI filling in the blanks. You can even clearly see the heavy duty knee pads Chan is wearing under his suit, not that he shouldn’t have them, only that more care wasn’t taken to make them less visible considering there’s no situational explanation for why he’d be wearing knee pads to attend this ceremony marking his decision to “adopt” a baby panda at a random zoo in a fictional country where almost everyone speaks Mandarin.

The baby panda has become a viral star because of its “unique” look with one eye patch smaller than the other. A sheik apparently decides he must have this panda and hires a bunch of mercenaries to kidnap it when his attempts to buy it fail. Of course, Jackie can’t let this happen and is determined to protect the baby panda from the international kidnappers. A panda is after all a symbol of China itself which can’t simply be bought by outside powers or the super rich while many of the mercenaries, who it’s implied are probably Eastern European, speak with American accents though in a stroke of luck, the main two turn out to be huge Jackie Chan fans and decide to help him so they aren’t that bad really while the leader actually seems to be Chinese anyway. That said, the guards at the zoo are both American and are shown to be slacking off at their job, eating donuts while remarking that they have an easy day ahead of them. It turns out the sheik had a heartrending reason for wanting the panda which wasn’t about the excesses of the super rich and Jackie’s decision to help him out paints China as generous and compassionate rather than coldhearted and possessive over its pandas.

In any case, despite the mild violence of the action scenes the film appears to be aimed at a family audience and has plenty of farcical humour as Jackie and Zhuzhu try to outsmart the kidnappers and save the panda who is eventually deposited at a panda park in China proper which is to say brought home again, where it belongs. The panda is rendered in unconvincing CGI but as using an actual panda would not be appropriate perhaps that really is the best solution and at least it’s a pretty cute CGI panda even if it’s obvious that it was added afterwards. The panda rescue being so successful, Jackie also gets asked to rescue the late Queen’s kidnapped corgis though it’s quite clear that he already has a very busy social calendar and is really getting fed up with doing action. Even so it has to be said that there’s already a Panda Plan 2 scheduled for release later this year, so he’ll presumably have to do some rescuing again.

Panda Plan is released in the US on Digital, Blu-ray & DVD February 18 courtesy of Well Go USA.

Trailer (English subtitles)