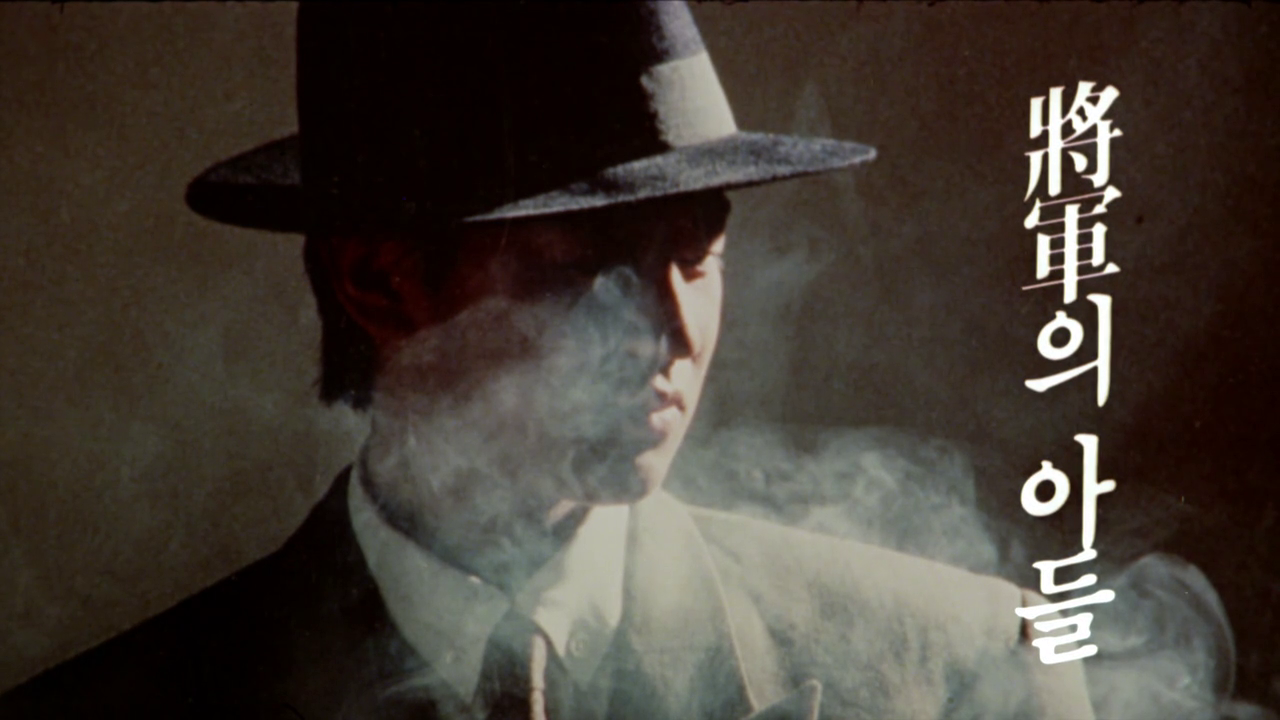

Im Kwon-taek may have been among the first Korean film directors to secure a spot on the international festival circuit, but his long and meandering career began with action cinema which is where his early ‘90s blockbuster trilogy General’s Son (將軍의 아들 / 장군의 아들, Jangguneui Adeul) returns him. Quite clearly influenced by recent Hong Kong martial arts movies, ninkyo eiga yakuza dramas from Japan, and episodic fighting comics, General’s Son creates legend from recent history in further mythologising a real life street king who eventually shifted into politics in the 1950s which might be one shift too far in terms of the film’s complicated politics.

This first instalment in the trilogy opens with Doo-han (Park Sang-min) being released from prison after apparently having been picked up for sneaking into a Japanese cinema and getting into some kind of fight. An orphan, Doo-han has spent his life on the streets as a beggar but also has a deep love of the movies and is determined to get a job at the cinema, eventually landing one as a sandwich board/announcements guy parading through the streets shouting about what’s currently on for which he gets two tickets on top of his pay. The tickets become a bone of contention when some lowlife punks try to cheat him out of them, but Doo-han is a handy boy and so he manages to beat the guys up and get the tickets back despite being stabbed in the thigh. The altercation brings him to the attention of a local gang boss who decides to recruit him because he’s in need of street muscle and even helps him get a job at the cinema which turns out to be a hub for the local organised crime community.

The complication is that this small area of Jongno which is ruled by the gangs is also the last remaining outpost of a “free” Korea where Japanese interference is apparently minimal. There is, however, a Japanese gang presence in the form of traditional yakuza led by the youthful and handsome Hayashi (Shin Hyun-joon), who becomes the central if not direct villain. In typical gangster origin fashion, Doo-han climbs the ranks by using his fists, taking down one big boss after another but, crucially, only while his own guys collectively decide to make way for him. As one after the other is killed or arrested, they each affirm that their era has passed, they’ve been beaten, and it’s all up to Doo-han now. In fact, in this highly ritualised setting, most fights ends with the defeated party solemnly admitting that they have lost and will politely leave Jongno at their earliest opportunity.

As for Doo-han himself, he belongs to the noble brand of gangster and becomes something of a folk hero for his spirited defence of the ordinary man in the face of “Japanese tyranny”. Of course, that ignores all the ways in which the gangsters themselves could be quite oppressive and the film does indeed resist any mention of how they make their money other than a veiled allusion to collecting protection from the market traders in order to keep them safe from harassment by the Japanese.

At the end of the film, Doo-han receives an explanation for all the crytic hints to the film’s title to the effect that he is the son of a legendary general in the Independence Movement. His role is, in effect, to be the general in Jongno holding back the Japanese incursion and saving the soul of Korea from being despoiled by colonisers intent on erasing its essential culture. Just as his father is fighting in Manchuria, Doo-han is “fighting for our liberty” on the streets of Jongno while standing up for the oppressed wherever he finds them, including the gisaeng one of whom he saves from being sold into a Chinese brothel by her father by robbing wealthy Japanese officials to pay her debt. What he’s mostly doing, however, is fighting with fellow gangsters, proving himself in tests of strength which leave his opponents breathing but humiliated and thereafter removing themselves from the game in graceful defeat. It’s unlikely the Japanese will do the same, but Doo-han will be monitoring the streets until they do.