Little known outside of Japan, Yoshitaro Nomura is most closely associated with post-war noir and particularly with adaptations of Seicho Matsumoto’s detective novels, yet he had a wide and varied filmography directing in several genres including musicals and period dramas. The son of silent movie director Hotei Nomura, he spent the bulk of his career at Shochiku which had and to some degree still has a strong studio brand which leans towards the wholesome even if his own work was often in someway controversial such as in the shocking child abuse drama The Demon or foregrounding of leprosy in Castle of Sand. Part of the studio’s series of double-length epics, 1964’s Scarlet Camellia (五瓣の椿, Goben no Tsubaki) is nevertheless an unusual entry in Nomura’s filmography, adapting a novel by Shugoro Yamamoto essentially setting a policier in feudal Japan and perhaps consequently shot largely on stage sets rather than on location.

Nomura opens with artifice as Shino (Shima Iwashita) stares daggers at an actor on the stage but later returns to his rooms every inch the giggling fan before finally offing him with her ornate silver hairpin leaving behind only the blood red camellia of the title. The first in a series of killings later branded the Camellia Murders, we later realise that the actor had to die because of his illicit relationship with Shino’s mother whom he brands a “nympho” and as we later discover had several extra-marital lovers. Extremely close to her father who, as we’re told, perished in a fire while resting in the country due to his terminal tuberculosis, Shino is apparently on a quest for revenge against the faithless men who humiliated him though her feelings towards her mother seem far more complex.

Indeed, Shino regards her mother’s carrying on as “dirty” and seems particularly prudish even as she wields her sex appeal as a weapon in her quest for vengeance. Yet it’s not so much the free expression of sexuality which seems to be at fault but excess and irresponsibility. Shino resents her mother primarily for the ways in which she made her father suffer, off having fun with random men while he shouldered the burden of her family business which, Shino might assume, has contributed to his illness. Aoki (Go Kato), the Edo-era policeman to whose narrative perspective the second half turns, advances a similar philosophy in that there’s nothing wrong with having fun, he has fun at times too, but people have or at least should have responsibilities towards each other which the caddish targets of the Camellia Killer have resolutely ignored. He can’t say that he condones the killer’s actions, but neither can he condemn them because her motivations are in a sense morally justifiable.

Realising the end is near, Shino indulges in a very modern serial killer trope in leaving a note for Aoki alongside one of her camellias in which she claims that she is exacting vengeance for “crimes not punishable by law”. There was nothing legally wrong in the way these men treated her mother or any other woman, but it is in a sense a moral crime. “You’re a woman and I’m a woman too” she later tells another scorned lover, a mistress thrown over by her patron with two small children after he tired of her, as she hands over a large sum of money and encourages her to return to her family in the country. Shino’s quest is essentially feminist, directed against a cruel and patriarchal society in which the use and abuse of women is entirely normalised, yet it is also slightly problematic in her characterisation of her mother as monstrous in her corrupted femininity for daring to embrace her sexuality in exactly the same way as her male counterparts though they, ironically, mainly seem to have been after her money rather than her body.

Shino’s mother’s death is indeed regarded as “punishment from heaven” presumably for her sexual transgressions and neglect of her family, rejecting both the roles of wife and mother in a ceaseless quest for pleasure. Yet even in her resentment, Shino’s ire is directed firmly at the men taking the last of her targets to task when he justifies himself that women enjoy sex too and are therefore equally complicit by reminding him that he gets his moment of pleasure for free but the woman may pay for it for the rest of her life. Just as Shino’s mother neglected her family, the men harm not only their wives in their illicit affairs but cause concurrent damage to the mistresses they may later disown and the illegitimate children they leave behind. Abandoning the naturalism of his contemporary crime dramas for something much more akin to a ghost film with his eerie lighting transitions and grim tableaux of the skewered victims, Nomura crafts a melancholy morality tale in which the wronged heroine turns the symbol of constrained femininity back on the forces of oppression but is eventually undone by the unintended consequences of her quest for vengeance even as she condemns the architect of her misfortune to madness and ruin.

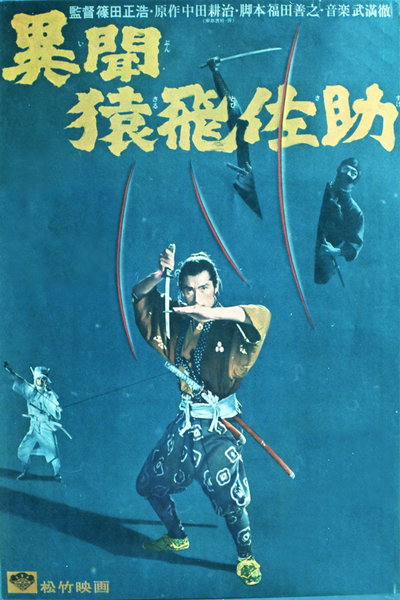

Nothing is certain these days, so say the protagonists at the centre of Masahiro Shinoda’s whirlwind of intrigue, Samurai Spy (異聞猿飛佐助, Ibun Sarutobi Sasuke). Set 14 years after the battle of Sekigahara which ushered in a long period of peace under the banner of the Tokugawa Shogunate, Samurai Spy effectively imports its contemporary cold war atmosphere to feudal Japan in which warring states continue to vie for power through the use of covert spy networks run from Edo and Osaka respectively. Sides are switched, friends are betrayed, innocents are murdered. The peace is fragile, but is it worth preserving even at such mounting cost?

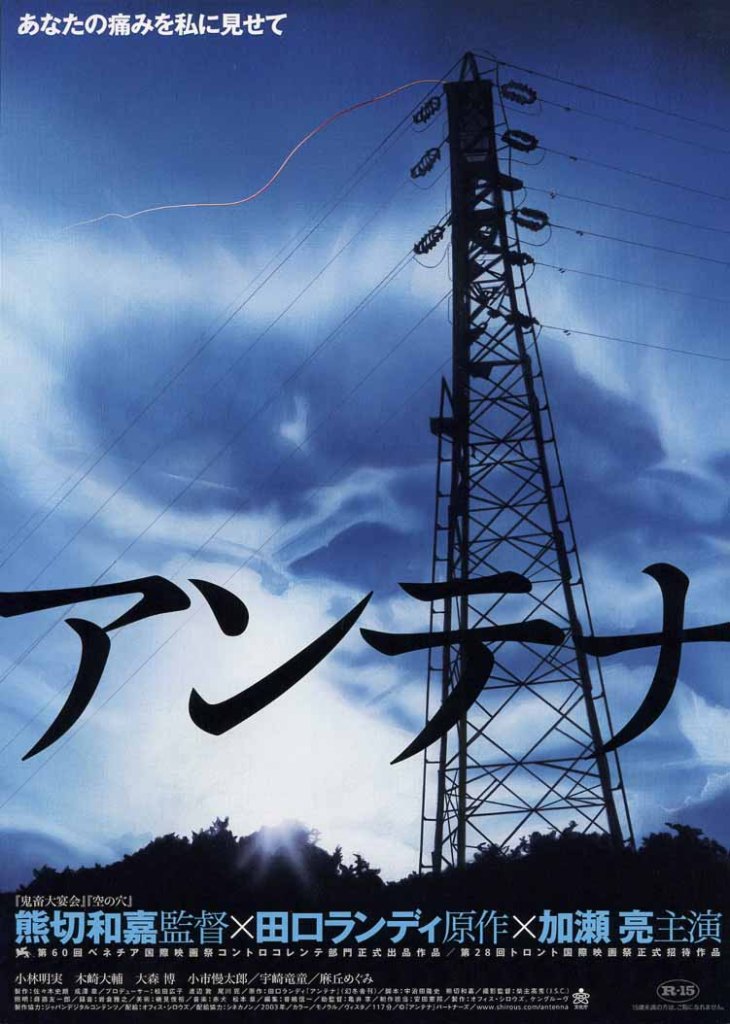

Nothing is certain these days, so say the protagonists at the centre of Masahiro Shinoda’s whirlwind of intrigue, Samurai Spy (異聞猿飛佐助, Ibun Sarutobi Sasuke). Set 14 years after the battle of Sekigahara which ushered in a long period of peace under the banner of the Tokugawa Shogunate, Samurai Spy effectively imports its contemporary cold war atmosphere to feudal Japan in which warring states continue to vie for power through the use of covert spy networks run from Edo and Osaka respectively. Sides are switched, friends are betrayed, innocents are murdered. The peace is fragile, but is it worth preserving even at such mounting cost? Scarring, both literal and mental, is at the heart of Kazuyoshi Kumakiri’s third feature, Antenna (アンテナ). Though it’s ironic that indentation should be the focus of a film whose title refers to a sensitive protuberance, Kumakiri’s adaptation of a novel by Randy Taguchi is indeed about feeling a way through. Anchored by a standout performance from Ryo Kase, Antenna is a surreal portrait of grief and repressed guilt as a family tragedy threatens to consume all of those left behind.

Scarring, both literal and mental, is at the heart of Kazuyoshi Kumakiri’s third feature, Antenna (アンテナ). Though it’s ironic that indentation should be the focus of a film whose title refers to a sensitive protuberance, Kumakiri’s adaptation of a novel by Randy Taguchi is indeed about feeling a way through. Anchored by a standout performance from Ryo Kase, Antenna is a surreal portrait of grief and repressed guilt as a family tragedy threatens to consume all of those left behind.