Film was the primary medium for propaganda and Japan had been pumping out increasingly patriotic fare under the National Policy programme since the late 1930s but what’s interesting about those which appeared towards the war’s end is that they do not try to sugarcoat the situation or pretend that the conflict is going well, rather they use the encroaching sense of desperation as an additional motivator to get all hands on deck. Released on Aug. 5, 1945, Three Women of the North (北の三人, Kita no Sannin) was the last propaganda film to be produced and the only film currently screening when the war ended on Aug. 15. Of course, after that it was swiftly withdrawn by the Occupation forces never to be seen again except perhaps as a historical document.

Like The Most Beautiful, the film skews accidentally feminist in its focus on three female radio operators who seem to be regarded as something of pioneers in the field. After encountering technical issues, a plane with a top secret mission is guided into an airfield in Aomori by nothing more than the voice of radio operator Sumiko (Setsuko Hara) yet on landing the pilot expresses surprise apparently stunned that a young woman would be able to perform such a stellar job. The sexist attitudes seem almost set up so they can be shot down, the pilot is quickly corrected by the ground control chief (Takashi Shimura) who explains “nowadays women can become excellent radio operators.”

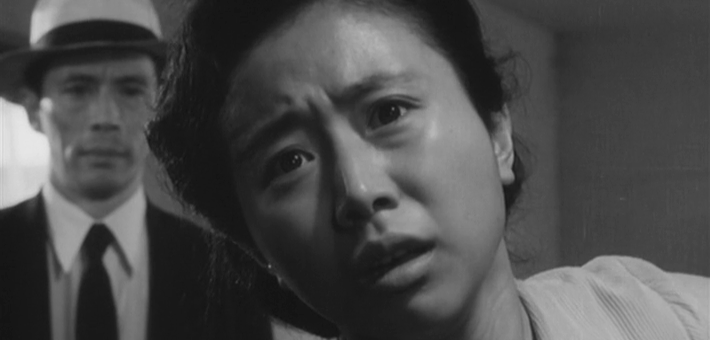

Of course, this is born of necessity seeing as at this late stage there is a huge untapped resource of young and widowed middle-aged women previously discouraged from getting directly involved with the war effort. In earlier propaganda films, the most important thing a woman could do was get married and particularly to a young man who was going to the war, but this time a conflict develops between two of the women, Yoshie (Hideko Takamine) and Sumiko, because Sumiko declined to marry Yoshie’s brother Kazuo before he left because she too wanted to do her bit for the war effort and would not have been able to do so as a married woman. On learning from Yoshie that Kazuo has been killed after volunteering to lead a suicide mission, she breaks down in tears and cries that she should have married him but Yoshie, who has forgiven her on learning of her patriotic reasoning, tells her that she has done the right thing and her brother would be proud of her for serving her country.

Meanwhile, at another airfield even deeper into the frozen north their friend Akiko (Hisako Yamane) has a developed a fondness for a research scientist but their romance is of course frustrated by the war. In a moment of fraught emotion, he tells her that he will be returning after delivering his findings and she should wait for him there which is almost to say that they will be granted their romantic resolution once the war is over. The curious thing is that Hara (Shin Saburi) is a weather scientist whose cloud forecasts have apparently been very useful to the pilots. A slightly strange diversion sees the film try to argue that at this point the greatest threat to the Japanese war effort is the weather, which aside from sounding like a very British excuse makes very little sense even if it is obviously a factor in mission success.

The radio operators obviously can’t do much about the weather, but they can pull together with plucky spirit dedicating themselves to the national good and giving all to the war effort. While Sumiko and Yoshie are having their emotional confrontation they’re interrupted by a trio of young women who were supposed to be getting a radio demonstration from Sumiko but they’ve come to say they can’t make it because one of the other girl’s mothers has been taken ill so they’re walking up the snowy mountain to the observatory in the middle of the night to send her back and take over her shift. When the radio operator on the special flight is taken down by pneumonia (the weather, again), Yoshie volunteers insisting that she’s prepared if the worst should happen but on landing remarks that she couldn’t have got through it without Sumiko and Akiko on the other end of the line resting their success on female solidarity. Though it’s clear the film was made on a shoe string it does feature special effects by none other than Eiji Tsuburaya along with some well conceived action sequences that lend an uncomfortably thrilling note to this extremely late entry into the realms of propaganda filmmaking.