Criminally unknown in the Anglophone world, where Tai Kato is remembered at all it’s for his contribution to Toei’s ninkyo eiga series though his best known piece is likely to be post-war take on High Noon made at Shochiku, By a Man’s Face Shall You Know Him in which a jaded doctor finds himself caught in the middle of rising tensions between local Japanese gangsters and Zainichi Koreans. Kato’s distinctive visual style shooting from extreme low angles with a preference for long takes, closeups and deep focus already make him an unusual presence in the Toei roster, but there can be few more unusual entries in the studio’s back catalogue than the wilfully anarchic Sasuke and his Comedians (真田風雲録, Sanada Fuunroku), a bizarre mix of musical comedy, historical chanbara, and ninja movie, loosely satirising the present day student movement and the limits revolutionary idealism.

An opening crawl introduces us to the scene at Sekigahara, a legendary battle of 1600 that brought an end to Japan’s warring states period and ushered in centuries of peace under the Tokugawa. Onscreen text explains that this is the story of the boys of who came of age in such a warlike era, giving way to a small gang of war orphans looting the bodies of fallen soldiers and later teaming up with a 19-year-old former samurai realising that the world as he knew it has come to an end. Soon the gang is introduced to the titular Sasuke who, as he explains, has special powers having been irradiated during a meteor strike as a baby. Recognising him as one of them, the war orphans offer to let Sasuke join their gang, but he declines because he’s convinced they’ll eventually reject him in fear of his awesome capabilities. Flashing forward 15 years, the kids are all grown up and the only girl, Okiri (Misako Watanabe), is still carrying a torch for Sasuke (Kinnosuke Nakamura) who dutifully reappears as the gang find themselves drawn into a revolutionary movement led by Sanada Yukimura (Minoru Chiaki) culminating in the Siege of Osaka in 1614.

Don’t worry, this is not a history lesson though these are obviously extremely well known historical events the target audience will be well familiar with. A parallel is being drawn with the young people of early ‘60s Japan who too came of age in a warlike era and who are now also engaging in minor revolutionary thought most clearly expressed in the mass protests against the ANPO treaty in 1960 which in a sense failed because the treaty was indeed signed in spite of public opinion. Kato’s Sanada Yukimura is a slightly bumbling figure, first introduced banging his head on a low-hanging beam, wandering the land in search of talented ronin to join up with the Toyotomi rebellion against the already repressive Tokugawa regime. His underling sells this to the gang as they overlook a mile long parade of peasants headed to Osaka Castle as a means of bringing about a different future that they can’t quite define but imply will be less feudal and more egalitarian which is how they’ve caught the attention of so many exploited farmers.

Of course, we all already know how the Siege of Osaka worked out (not particularly well for anyone other than the Tokugawa) so we know that this version of the 16th century better world did not come to pass the implication being that the 1960s one won’t either. The nobles are playing their own game, the Toyotomi trying to cut deals but ultimately being betrayed, while the gang fight bravely for their ideals naively believing in the possibility of victory. Sasuke, for his part, is a well known ahistorical figure popular in children’s literature and this post-modern adventure is in essence a kids’ serial aimed at a student audience, filled with humorous anachronisms and silliness while Kato actively mimics manga-style storytelling mixed with kabuki-esque effects. Boasting slightly higher production values than your average Toei programmer, location shooting gives way to obvious stage sets and fantastical set pieces of colour and light which are a far cry from the studio’s grittier fare with which Kato was most closely associated. That might be one reason that the studio was reportedly so unhappy with the film that it almost got Kato fired, but nevertheless its strange mix of musical satire and general craziness remain an enduring cult classic even in its ironic defeatism.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

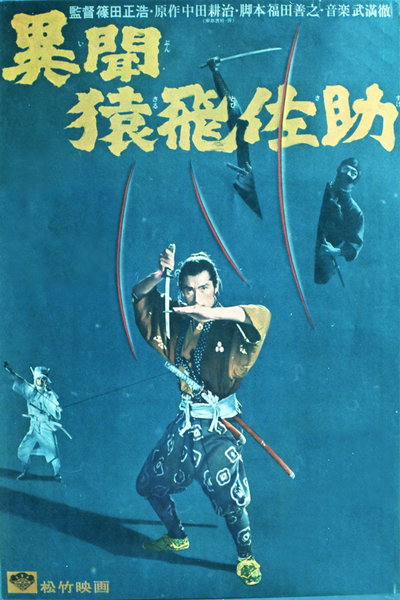

Nothing is certain these days, so say the protagonists at the centre of Masahiro Shinoda’s whirlwind of intrigue, Samurai Spy (異聞猿飛佐助, Ibun Sarutobi Sasuke). Set 14 years after the battle of Sekigahara which ushered in a long period of peace under the banner of the Tokugawa Shogunate, Samurai Spy effectively imports its contemporary cold war atmosphere to feudal Japan in which warring states continue to vie for power through the use of covert spy networks run from Edo and Osaka respectively. Sides are switched, friends are betrayed, innocents are murdered. The peace is fragile, but is it worth preserving even at such mounting cost?

Nothing is certain these days, so say the protagonists at the centre of Masahiro Shinoda’s whirlwind of intrigue, Samurai Spy (異聞猿飛佐助, Ibun Sarutobi Sasuke). Set 14 years after the battle of Sekigahara which ushered in a long period of peace under the banner of the Tokugawa Shogunate, Samurai Spy effectively imports its contemporary cold war atmosphere to feudal Japan in which warring states continue to vie for power through the use of covert spy networks run from Edo and Osaka respectively. Sides are switched, friends are betrayed, innocents are murdered. The peace is fragile, but is it worth preserving even at such mounting cost?