The close relationship between two women is disrupted by the reintroduction of a man in Yasuzo Masumura’s fictionalised account of the rivalry between the wife and mother of pioneering Japanese doctor Seishu Hanaoka. Scripted by Kaneto Shindo and adapted from the novel by Sawako Ariyoshi, the refocusing of the narrative is apparent in its title, not the life of but The Wife of Seishu Hanaoka (華岡青洲の妻, Hanaoka Seishu no Tsuma) less a tale of scientific endeavour than of domestic rivalry born of the inherently patriarchal social codes of the feudal society which cannot but help pit one woman against another while forcing each of them to play a role they may not wish to fulfil in order to secure their status and therefore their survival.

Samurai’s daughter Kae (Ayako Wakao) first catches sight of the beautiful Otsugi (Hideko Takamine) at only eight years old and is instantly captivated by her, a fascination which persists well into adulthood when she is approached to marry into the Hanaoka household as wife to oldest son Seishu (Raizo Ichikawa) away studying to become a doctor like his father. Kae’s father originally objects to the match because of the class difference between the two families, Seishu’s father Naomichi (Yunosuke Ito) being only a humble country doctor of peasant stock whereas they had envisaged a grander station for their only daughter. Yet Kae is already old not to be married and continues to decline prospective suitors and so her mother and nanny (Chieko Naniwa) are minded to put it directly to her discovering that she is in fact more than willing to become a Hanaoka though mostly it seems in order to get close to Otsugi whom she has continued to idolise.

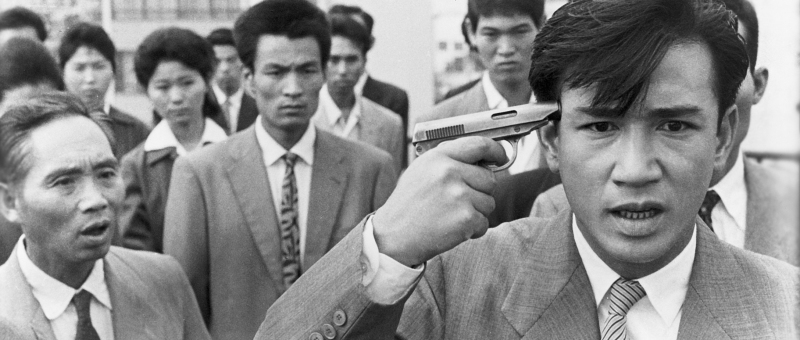

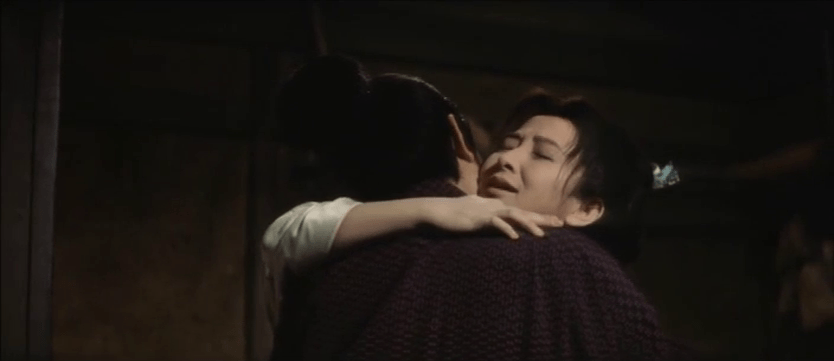

The strange thing is that the wedding is conducted in Seishu’s absence, a medical text standing in for him while Kae in effect marries her mother-in-law Otsugi. These early days are spent in blissful tranquility as Kae does her best to be the ideal daughter-in-law, Otsugi even remarking that she’s come to love her more than a daughter. The two women share a room, Kae often staring longingly at the back of Otsugi’s head, their relationship one of mutual respect and affection that allows them to forget their respective stations but when three years later Seishu finally returns, it forces them apart in reverting to the roles of wife and mother their statuses conferred only by proximity to a man.

Pregnant with her first child and about to become a mother herself, Kae’s resentment towards Otsugi begins to boil over. In an ironic premonition of the way the relationship between Masumura and his muse would eventually break down, she claims to have seen through Otsugi’s beauty and concluded that she is cold and calculating believing that she only brought her into the household as an unpaid servant forcing her to work a loom to raise money for Seishu’s medical training. Alternately jealous and condescending, Otsugi’s resentment is mediated through attempts to undermine her daughter-in-law’s authority finally leading to an ironic and absurdist battle between the two as they attempt to outdo each other volunteering to become test subjects for Seishu’s ongoing experiments to discover a safe anaesthetic in order save patients who require surgery but cannot endure the trauma.

The marriage itself perhaps represents a moment of change in the feudal society, it becoming clear that the samurai are on their way down while skill and knowledge will define success in this new age of enlightenment. While Seishu works on his anaesthetic, the superstitious local community begins to view the Hanaokas with suspicion, believing that the misfortune that befalls them is the result of a curse owing to the large number of cats and dogs which have become casualties of Seishu’s failed experiments while a pedlar brings news of a mysterious disease attributed to the rain which is in fact due to mass malnutrition following a famine caused by the bad weather. When news of Seishu’s prowess as a doctor spreads they are soon overwhelmed with patients, many of whom cannot pay but are seemingly treated anyway.

Seishu’s eventual victory is one of science over superstition, but it also requires faith which is the battleground contested between wife and mother. Having found a successful solution in cats, Seishu needs human test subjects with both instantly volunteering only to become locked into an absurd, internecine contest to prove who is the most self-sacrificing. The competition goes so far that it effectively becomes a game of dare with each determined to be the one to die for Seishu’s discovery but later realising that the stakes are even higher than first assumed because the winner will be dead but the loser saddled with guilt and possible ostracisation as someone who allowed their mother/daughter-in-law to die to in their place.

Even so, the pair of them are described as “wonderful examples of womanhood” in their willingness to risk their lives for their “master’s success”. Kae is reminded that a woman’s job is to give birth to a healthy baby, later weaponising her ability to do so as currency in realising that Otsugi has all the control but the one thing she can’t do is bear Seishu’s child. Ironically enough, the cases Seishu is trying to treat are of aggressive breast cancer, the oft repeated maxim being that a woman’s breasts are her life and to remove them is as good as killing her contributing to the sense that maternity is the only thing that gives a woman’s life meaning. It’s not without irony that the first successful surgery under anaesthesia directly juxtaposes a massive tumour removed from a woman’s breast with a baby being removed from a pregnant Kae who, at this point having lost her sight as a consequence of Seishu’s experiments, must bear the pain with no relief.

Brought together by tragedy, Kae comes to a better understanding of her relationship with her mother-in-law only after she dies learning to see her once again as the kind and beautiful woman she met at eight years old while her unmarried sister-in-law having witnessed their painful war of attrition prays that she won’t be reborn as a woman glad that she was never forced to become a bride nor a mother-in-law. “The struggles of the women in this house were in the end just to bring up one man” she laments, suggesting that Seishu most likely noticed the conflict between the two and used it to his advantage in getting them to participate in his experiments as they desperately tried to prove themselves the better through dying for his love.

Going one step further, it seems that being a woman is an exercise in futility the only source of success lying paradoxically in birth or death alone, the natural affection between Otsugi and Kae neutered by the presence of Seishu who inserts himself as the pole around which they must dance for their survival. Kae becomes a local legend, a woman who sacrificed her sight in service of her husband but now rejects this mischaracterisation of her life along with the implication that it’s somehow a wife’s duty to deplete herself for her husband’s gain retreating entirely from the society of others while Seishu’s practice continues to prosper. Even so Masumura ends on a note of irony in the literal transformation of Kae into the figure of Otsugi recreating the opening scene as she walks among the bright flowers she can no longer see.

Original trailer (no subtitles)