Generally speaking, murder mysteries progress along a clearly defined path at the end of which stands the killer. The path to reach him is his motive, a rational explanation for an irrational act. Yet, looking deeper there’s usually something else going on. It’s easy to blame society, or politics, or the economy but all of these things can be mitigating factors when it comes to considering the motives for a crime. Gukoroku – Traces of Sin (愚行録), the debut feature from Kei Ishikawa and an adaptation of a novel by Tokuro Nukui, shows us a world defined by unfairness and injustice, in which there are no good people, only the embittered, the jealous, and the hopelessly broken. Less about the murder of a family than the murder of the family, Gukoroku’s social prognosis is a bleak one which leaves little room for hope in an increasingly unfair society.

Generally speaking, murder mysteries progress along a clearly defined path at the end of which stands the killer. The path to reach him is his motive, a rational explanation for an irrational act. Yet, looking deeper there’s usually something else going on. It’s easy to blame society, or politics, or the economy but all of these things can be mitigating factors when it comes to considering the motives for a crime. Gukoroku – Traces of Sin (愚行録), the debut feature from Kei Ishikawa and an adaptation of a novel by Tokuro Nukui, shows us a world defined by unfairness and injustice, in which there are no good people, only the embittered, the jealous, and the hopelessly broken. Less about the murder of a family than the murder of the family, Gukoroku’s social prognosis is a bleak one which leaves little room for hope in an increasingly unfair society.

When we first meet Tanaka (Satoshi Tsumabuki) he’s riding a bus. Ominous music plays as a happy family gets off but the real drama starts when another passenger irritatedly instructs Tanaka to give up his seat so an elderly lady can sit down. He snorts a little but gets up only to fall down next to the steps to the doors and subsequently walk off with a heavy limp. The man who told him to move looks sheepish and embarrassed, but as soon as the bus passes from view Tanaka starts walking normally, an odd kind of smirk on his face in thought of his petty revenge.

In one sense the fact that Tanaka faked a disability is irrelevant, the man did not consider that Tanaka may himself have needed a seat despite looking like a healthy man approaching early middle age. Perhaps, he’ll think twice about making such assumptions next time – then again appearances and assumptions are the lifeblood of this mysteriously complicated case.

Tanaka has a lot on his plate – his younger sister, Mitsuko (Hikari Mitsushima), has been arrested for neglecting her daughter who remains in intensive care dangerously underweight from starvation. In between meeting with her lawyer and checking on his niece, he’s also working on an in-depth piece of investigative reporting centring on a year old still unsolved case of a brutal family murder. Tanaka begins by interviewing friends of the husband before moving onto the wife who proves much more interesting. Made for each other in many ways, this husband and wife duo had made their share of enemies any of whom might have had good reason for taking bloody vengeance.

The killer’s identity, however, is less important than the light the crime shines on pervasive social inequality. As one character points out, Japan is a hierarchical society, not necessarily a class based one, meaning it is possible to climb the ladder. This proves true in some senses as each of our protagonists manipulates the others, trying to get the best possible outcome for themselves. These are cold and calculating people, always keeping one eye on the way they present themselves and the other on their next move – genuine emotion is a weakness or worse still, a tool to be exploited.

The key lies all the way back in university where rich kids rule the roost and poor ones work themselves to the bone just trying to keep up. There are “insiders” and “outsiders” and whatever anyone might say about it, they all secretly want in to the elite group. Here is where class comes in, no matter how hard you try for acceptance, the snobby rich kids will always look down on those they feel justified in regarding as inferior. They may let you come to their parties, take you out for fancy meals, or invite you to stay over but you’ll never be friends. The irony is that the system only endures because everyone permits it, the elites keep themselves on top by dangling the empty promise that someday you could be an elite too safe in the knowledge that they only hire in-house candidates.

Gradually Tanaka’s twin concerns begin to overlap. The traces of sin extend to his own door as he’s forced to examine the legacy of his own traumatic childhood and fractured family background. The reason the killer targeted the “happy” family is partly vengeance for a series of life ruining wrongs, but also a symbolic gesture stabbing right at the heart of society itself which repeatedly failed to protect them from harm. Betrayed at every turn, there’s only so much someone can take before their rage, pain, and disillusionment send them over the edge.

Despite the predictability of the film’s final twist, Ishikawa maintains tension and intrigue, drip feeding information as Tanaka obtains it though that early bus incident reminds us that even he is not a particularly reliable narrator. Ishikawa breaks with his grim naturalism for a series of expressionistic dream sequences in which hands paw over a woman’s body until they entirely eclipse her, a manifestation of her lifelong misuse which has all but erased her sense of self-worth. There are no good people here, only users and manipulators – even the abused eventually pass their torment on to the next victim whether they mean to or not. Later, Tanaka gets on another bus and gives up his seat willingly in what seems to be the film’s first and only instance of altruism but even this small gesture of resistance can’t shake the all-pervading sense of hopeless loneliness.

Gukoroku – Traces of Sin was screened at the 17th Nippon Connection Japanese film Festival.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

Self disgust is self obsession as the old adage goes. It certainly seems to ring true for the “hero” of Miwa Nishikawa’s latest feature, The Long Excuse (永い言い訳, Nagai Iiwake) , in which she adapts her own Naoki Prize nominated novel. In part inspired by the devastating earthquake which struck Japan in March 2011, The Long Excuse is a tale of grief deferred but also one of redemption and self recognition as this same refusal to grieve forces a self-centred novelist to remember that other people also exist in the world and have their own lives, emotions, and broken futures to dwell on.

Self disgust is self obsession as the old adage goes. It certainly seems to ring true for the “hero” of Miwa Nishikawa’s latest feature, The Long Excuse (永い言い訳, Nagai Iiwake) , in which she adapts her own Naoki Prize nominated novel. In part inspired by the devastating earthquake which struck Japan in March 2011, The Long Excuse is a tale of grief deferred but also one of redemption and self recognition as this same refusal to grieve forces a self-centred novelist to remember that other people also exist in the world and have their own lives, emotions, and broken futures to dwell on.

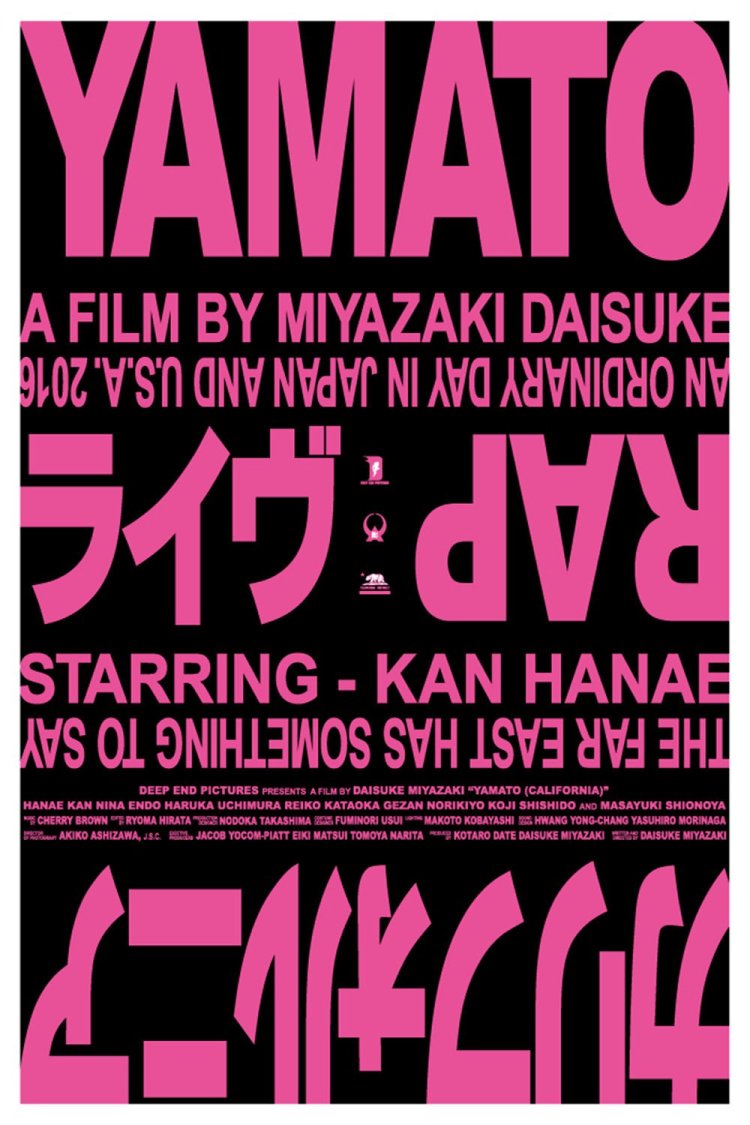

When you think of the American military presence in Japan, your mind naturally turns to Okinawa but the largest mainland US base is actually located not so far from Tokyo in a small Japanese town called Yamato which is also the ancient name for the modern-day country. The US has been a constant presence since the end of the second world war prompting resistance of varying degrees from both left and right either in resentment at perceived complicity in American foreign policy, or the desire to reform the pacifist constitution and rebuild an independent army capable of defending Japan alone. Daisuke Miyazaki’s second feature, Yamato (California) (大和(カリフォルニア) dramatises this long-standing issue through exploring the life of hip-hop enthusiast and Yamato resident Sakura (Hanae Kan) who idolises an art form born of political oppression in a country which she also feels oppresses her as a Japanese citizen living on the other side of the fence from land which technically still belongs to the US government.

When you think of the American military presence in Japan, your mind naturally turns to Okinawa but the largest mainland US base is actually located not so far from Tokyo in a small Japanese town called Yamato which is also the ancient name for the modern-day country. The US has been a constant presence since the end of the second world war prompting resistance of varying degrees from both left and right either in resentment at perceived complicity in American foreign policy, or the desire to reform the pacifist constitution and rebuild an independent army capable of defending Japan alone. Daisuke Miyazaki’s second feature, Yamato (California) (大和(カリフォルニア) dramatises this long-standing issue through exploring the life of hip-hop enthusiast and Yamato resident Sakura (Hanae Kan) who idolises an art form born of political oppression in a country which she also feels oppresses her as a Japanese citizen living on the other side of the fence from land which technically still belongs to the US government. “Memories are what warm you up from the inside. But they’re also what tear you apart” runs the often quoted aphorism from Haruki Murakami. SABU seems to see things the same way and indulges an equally surreal side of himself in the sci-fi tinged Happiness (ハピネス). Memory, as the film would have it, both sustains and ruins – there are terrible things which cannot be forgotten, no matter how hard one tries, while the happiest moments of one’s life get lost among the myriad everyday occurrences. Happiness is the one thing everyone craves even if they don’t quite know what it is, little knowing that they had it once if only for a few seconds, but if the desire to attain “happiness” is itself a reason for living could simply obtaining it by technological means do more harm than good?

“Memories are what warm you up from the inside. But they’re also what tear you apart” runs the often quoted aphorism from Haruki Murakami. SABU seems to see things the same way and indulges an equally surreal side of himself in the sci-fi tinged Happiness (ハピネス). Memory, as the film would have it, both sustains and ruins – there are terrible things which cannot be forgotten, no matter how hard one tries, while the happiest moments of one’s life get lost among the myriad everyday occurrences. Happiness is the one thing everyone craves even if they don’t quite know what it is, little knowing that they had it once if only for a few seconds, but if the desire to attain “happiness” is itself a reason for living could simply obtaining it by technological means do more harm than good?

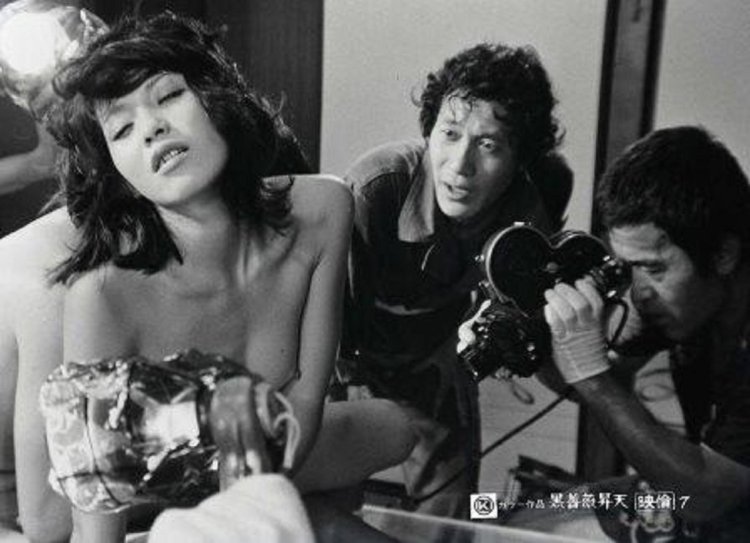

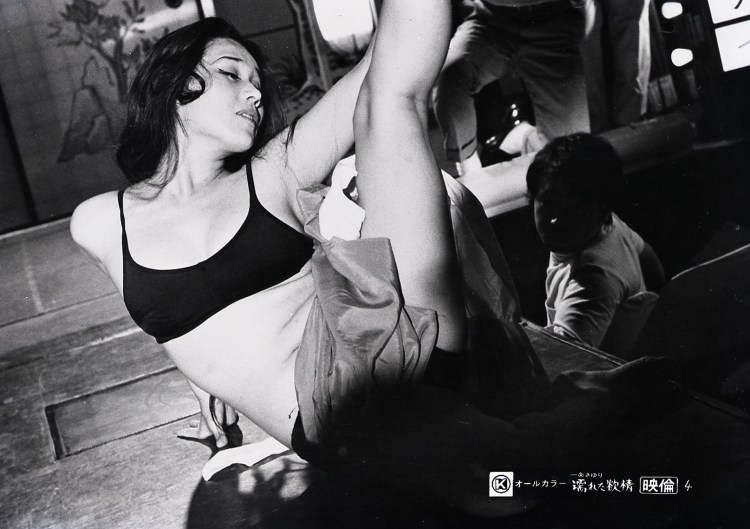

Each year the Nippon Connection film festival runs a retrospective programme alongside its collection of recent indie and mainstream hits. The subject for this year’s strand is Nikkatsu’s Roman Porno. Heading into the 1970s, Japanese cinema was in crisis mode as TV poached cinema audiences who largely stayed away from the successful genres of the 1960s including the previously popular youth, action, and yakuza movies which had been entertaining them for close to 20 years. Daiei, one of the larger studios known for glossy, big budget prestige fare alongside some lower budget genre offerings went bust in 1971, Shochiku kept up its steady stream of melodramas, but Nikkatsu found another solution. Taking inspiration from the “pink film” – a brand of soft core, mainstream pornography shown in specialised cinemas and made to exacting production standards, they created “Roman Porno” which made sex its selling point, but put big studio resources behind it, bringing in better actors and innovative directors to lend an air of legitimacy to its purely populist ethos.

Each year the Nippon Connection film festival runs a retrospective programme alongside its collection of recent indie and mainstream hits. The subject for this year’s strand is Nikkatsu’s Roman Porno. Heading into the 1970s, Japanese cinema was in crisis mode as TV poached cinema audiences who largely stayed away from the successful genres of the 1960s including the previously popular youth, action, and yakuza movies which had been entertaining them for close to 20 years. Daiei, one of the larger studios known for glossy, big budget prestige fare alongside some lower budget genre offerings went bust in 1971, Shochiku kept up its steady stream of melodramas, but Nikkatsu found another solution. Taking inspiration from the “pink film” – a brand of soft core, mainstream pornography shown in specialised cinemas and made to exacting production standards, they created “Roman Porno” which made sex its selling point, but put big studio resources behind it, bringing in better actors and innovative directors to lend an air of legitimacy to its purely populist ethos. Ecstacy of the Black Rose is a more comedic effort than most of Kumashiro’s output and takes an ironic look at the genre as a put upon director gets fed up when his leading actress falls pregnant and becomes obsessed with finding a woman whose moans he overheard at the dentist’s.

Ecstacy of the Black Rose is a more comedic effort than most of Kumashiro’s output and takes an ironic look at the genre as a put upon director gets fed up when his leading actress falls pregnant and becomes obsessed with finding a woman whose moans he overheard at the dentist’s. Following Desire received a Kinema Junpo award for best screenplay as well as the best actress prize for Hiroko Isayama who plays a stripper intent on taking down her rival for the top spot!

Following Desire received a Kinema Junpo award for best screenplay as well as the best actress prize for Hiroko Isayama who plays a stripper intent on taking down her rival for the top spot! Kumashiro’s Tamanoi Street of Joy takes place on the last day of legal prostitution in 1958 and follows the girls as they mark the occasion in their own particular ways.

Kumashiro’s Tamanoi Street of Joy takes place on the last day of legal prostitution in 1958 and follows the girls as they mark the occasion in their own particular ways. Further proving Kumashiro’s critical stature, Twisted Path of Love was among Kinema Junpo’s 1999 list of the greatest Japanese films of the 20th century. The story of a young man who returns to his hometown but attempts to shed his identity, burning a hole in the conventional village life through sex and violence, Twisted Path of Love also displays Kumashiro’s interesting use of common censorship techniques for artistic effect.

Further proving Kumashiro’s critical stature, Twisted Path of Love was among Kinema Junpo’s 1999 list of the greatest Japanese films of the 20th century. The story of a young man who returns to his hometown but attempts to shed his identity, burning a hole in the conventional village life through sex and violence, Twisted Path of Love also displays Kumashiro’s interesting use of common censorship techniques for artistic effect. Often regarded as Kumashiro’s masterpiece, The Woman with the Red Hair picked up a Kinema Junpo best actress award for Junko Miyashita, as well as ranking fourth in their annual best of the year list. The story centres on construction worker Kozo who, along with friend Takao, rapes his boss’ daughter who subsequently becomes pregnant. While she asks Takao to marry her, Kozo embarks on an affair with the mysterious red-haired woman.

Often regarded as Kumashiro’s masterpiece, The Woman with the Red Hair picked up a Kinema Junpo best actress award for Junko Miyashita, as well as ranking fourth in their annual best of the year list. The story centres on construction worker Kozo who, along with friend Takao, rapes his boss’ daughter who subsequently becomes pregnant. While she asks Takao to marry her, Kozo embarks on an affair with the mysterious red-haired woman. Another of Kumashiro’s most well-regarded Roman Porno, The World of the Geisha takes place in a geisha house in 1918 and examines the various tensions which exist between the women themselves and their customers who have come to the house to escape external political concerns. The film again demonstrates Kumashiro’s tendency to ironic commentary as he tampers with intertitles to make a point about censorship.

Another of Kumashiro’s most well-regarded Roman Porno, The World of the Geisha takes place in a geisha house in 1918 and examines the various tensions which exist between the women themselves and their customers who have come to the house to escape external political concerns. The film again demonstrates Kumashiro’s tendency to ironic commentary as he tampers with intertitles to make a point about censorship. Night of the Felines provides the inspiration for Kazuya Shirashi’s reboot Dawn of the Felines and follows the comical adventures of three prostitutes.

Night of the Felines provides the inspiration for Kazuya Shirashi’s reboot Dawn of the Felines and follows the comical adventures of three prostitutes. Stroller in the Attic is among the best known in the Roman Porno canon and adapts an Edogawa Rampo short story about a ’20s boarding house filled with eccentric guests.

Stroller in the Attic is among the best known in the Roman Porno canon and adapts an Edogawa Rampo short story about a ’20s boarding house filled with eccentric guests. Inspired by the same real life case as In the Realm of the Senses, Noburu Tanaka’s Sada and Kichi takes a more lurid look at the strange case of Abe Sada who strangled her lover after a brief affair and then cut off his genitals to wear as a kind of talisman.

Inspired by the same real life case as In the Realm of the Senses, Noburu Tanaka’s Sada and Kichi takes a more lurid look at the strange case of Abe Sada who strangled her lover after a brief affair and then cut off his genitals to wear as a kind of talisman. Nippon Connection aims to showcase all sides of Japanese cinema from the mainstream to arthouse and documentary and this, of course, includes animation.

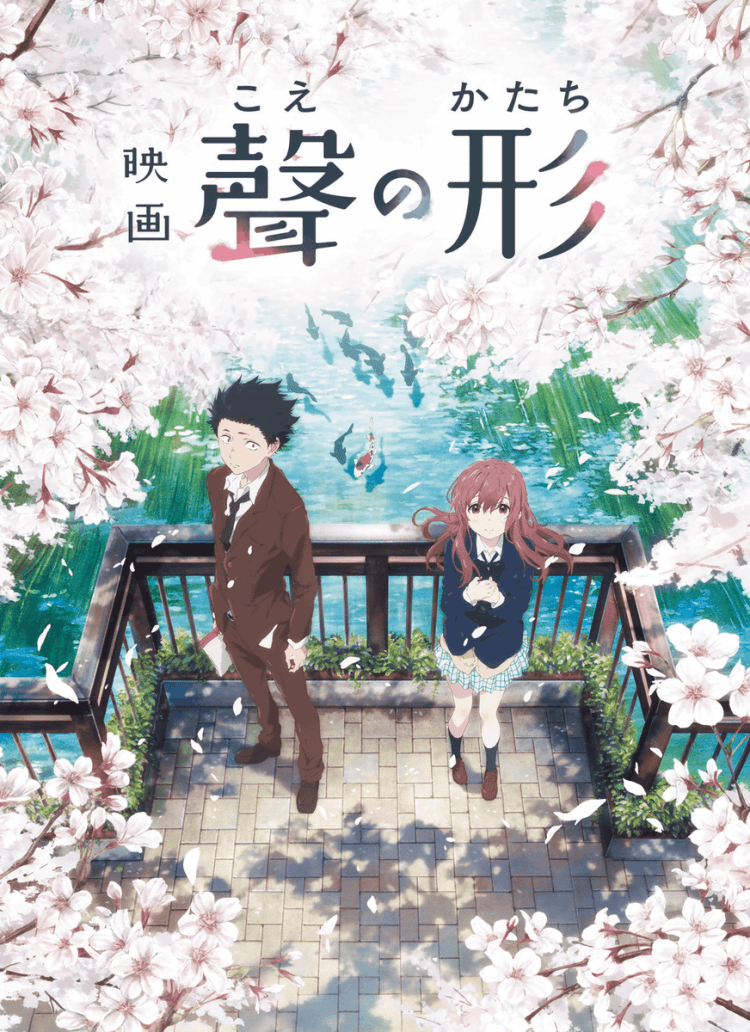

Nippon Connection aims to showcase all sides of Japanese cinema from the mainstream to arthouse and documentary and this, of course, includes animation. A hit at festivals around the world, A Silent Voice is a poignant tale about guilt, redemption, and attitudes to disability.

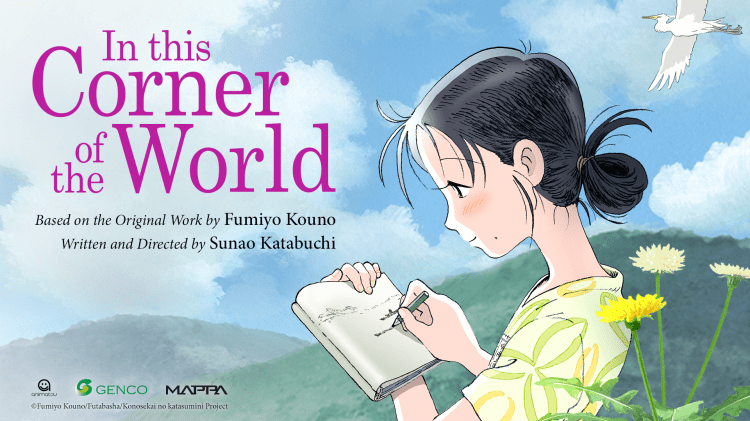

A hit at festivals around the world, A Silent Voice is a poignant tale about guilt, redemption, and attitudes to disability. Mai Mai Miracle’s Sunao Katabuchi returns with the multi-awardwinning In This Corner of the World – a coming of age story set in Hiroshima before and after the atomic bomb.

Mai Mai Miracle’s Sunao Katabuchi returns with the multi-awardwinning In This Corner of the World – a coming of age story set in Hiroshima before and after the atomic bomb. Chieri and Cherry is a charming puppet animation in which Chieri, who has recently lost her father, develops an intense bond with her stuffed toy, Cherry. Travelling to her grandmother’s house for her father’s funeral, Chieri experiences a fantastic adventure which helps her to cope with grief and fear of the future.

Chieri and Cherry is a charming puppet animation in which Chieri, who has recently lost her father, develops an intense bond with her stuffed toy, Cherry. Travelling to her grandmother’s house for her father’s funeral, Chieri experiences a fantastic adventure which helps her to cope with grief and fear of the future. Rudolf the Black Cat stars titular black cat Rudolf from Gifu who ends up accidentally homeless in Tokyo!

Rudolf the Black Cat stars titular black cat Rudolf from Gifu who ends up accidentally homeless in Tokyo! Poetic Landscapes – Recent Gems in Japanese Animation is a selection of some of the best in recent short animated films curated by Catherine Munroe Hotes.

Poetic Landscapes – Recent Gems in Japanese Animation is a selection of some of the best in recent short animated films curated by Catherine Munroe Hotes. Tokyo University of the Arts: Animation – a selection of animated graduation films from Tokyo University of the Arts.

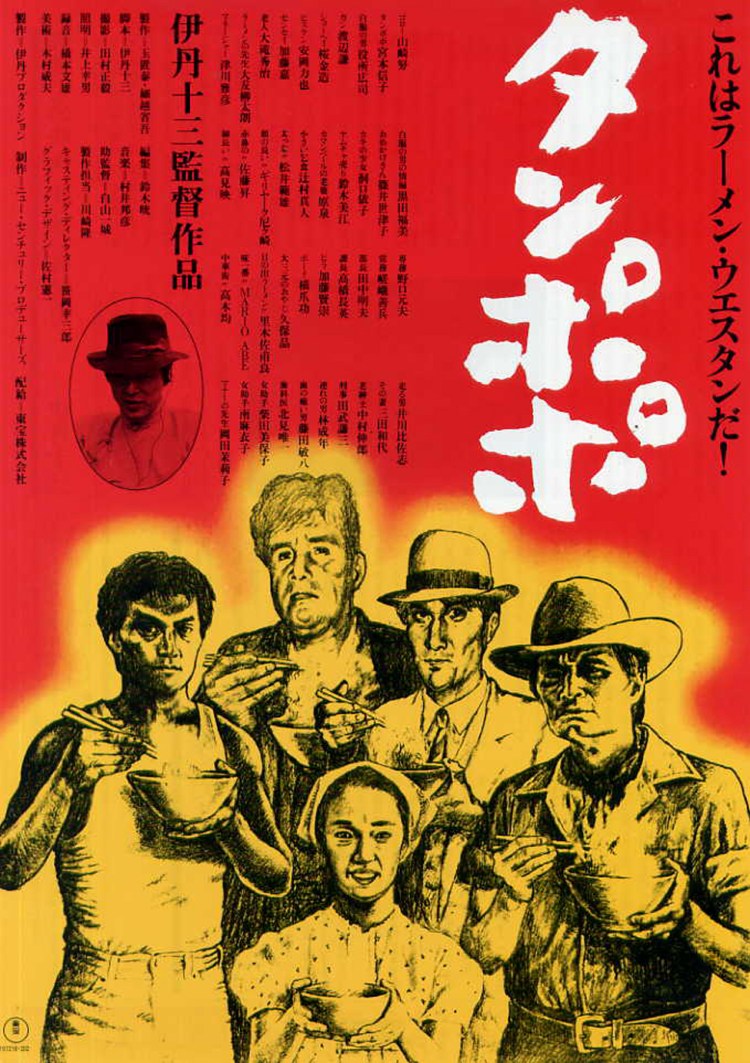

Tokyo University of the Arts: Animation – a selection of animated graduation films from Tokyo University of the Arts. Some people love ramen so much that the idea of a “bad” bowl hardly occurs to them – all ramen is, at least, ramen. Then again, some love ramen so much that it’s almost a religious experience, bound up with ritual and the need to do things properly. A brief vignette at the beginning of Juzo Itami’s Tampopo (タンポポ) introduces us to one such ramen expert who runs through the proper way of enjoying a bowl of noodle soup which involves a lot of talking to your food whilst caressing it gently before finally consuming it with the utmost respect. Ramen is serious business, but for widowed mother Tampopo it’s a case of the watched pot never boiling. Thanks to a cowboy loner and a few other waifs and strays who eventually become friends and allies, Tampopo is about to get some schooling in the quest for the perfect noodle whilst the world goes on around her. Food becomes something used and misused but remains, ultimately, the source of all life and the thing which unites all living things.

Some people love ramen so much that the idea of a “bad” bowl hardly occurs to them – all ramen is, at least, ramen. Then again, some love ramen so much that it’s almost a religious experience, bound up with ritual and the need to do things properly. A brief vignette at the beginning of Juzo Itami’s Tampopo (タンポポ) introduces us to one such ramen expert who runs through the proper way of enjoying a bowl of noodle soup which involves a lot of talking to your food whilst caressing it gently before finally consuming it with the utmost respect. Ramen is serious business, but for widowed mother Tampopo it’s a case of the watched pot never boiling. Thanks to a cowboy loner and a few other waifs and strays who eventually become friends and allies, Tampopo is about to get some schooling in the quest for the perfect noodle whilst the world goes on around her. Food becomes something used and misused but remains, ultimately, the source of all life and the thing which unites all living things. Nippon Connection returns for 2017 in just under a week’s time and to whet your appetite for all the amazing films about to shown in Frankfurt from May 23 – 28, the festival has re-launched its very own

Nippon Connection returns for 2017 in just under a week’s time and to whet your appetite for all the amazing films about to shown in Frankfurt from May 23 – 28, the festival has re-launched its very own  So,

So,  Japanese-American director Kimi Takesue’s 95 and 6 to Go was filmed over six years during which she travelled to Hawaii following the death of her grandmother to learn more about the history of her family. Talking to her grandfather about his life and her own stalled film project, Takesue neatly weaves the personal and the universal for a meditation on life, love, loss and endurance.

Japanese-American director Kimi Takesue’s 95 and 6 to Go was filmed over six years during which she travelled to Hawaii following the death of her grandmother to learn more about the history of her family. Talking to her grandfather about his life and her own stalled film project, Takesue neatly weaves the personal and the universal for a meditation on life, love, loss and endurance. Produced by Ian Thomas Ash (A2-B-C, -1287) Boys for Sale is the debut feature from Itako and focuses on the world of male prostitution in Tokyo’s Shinjuku 2-chome.

Produced by Ian Thomas Ash (A2-B-C, -1287) Boys for Sale is the debut feature from Itako and focuses on the world of male prostitution in Tokyo’s Shinjuku 2-chome. Come on Home to Sato is the debut feature from Yoshiki Shigee. Filmed over three years, the film follows the social workers and professionals involved with Kodomo no Sato – a safehaven for children of all ages and backgrounds in Osaka’s Nishinari district.

Come on Home to Sato is the debut feature from Yoshiki Shigee. Filmed over three years, the film follows the social workers and professionals involved with Kodomo no Sato – a safehaven for children of all ages and backgrounds in Osaka’s Nishinari district. The intriguingly titled Gui Aiueo:S A Stone From Another Mountain To Polish Your Own Stone is a strange road movie/documentary/performance piece from Go Shibata featuring UFOs, hermits, and sustainable toilets.

The intriguingly titled Gui Aiueo:S A Stone From Another Mountain To Polish Your Own Stone is a strange road movie/documentary/performance piece from Go Shibata featuring UFOs, hermits, and sustainable toilets. A selection of three short NHK documentaries :

A selection of three short NHK documentaries : Gilles Laurent’s La Terre Abandonée follows the residents of Tomioka who refused to obey the evacuation order after the meltdown of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant.

Gilles Laurent’s La Terre Abandonée follows the residents of Tomioka who refused to obey the evacuation order after the meltdown of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant. Steven Okazaki’s Mifune: The Last Samurai is an attempt to chart the legendary actor’s career as it intersects with the history of samurai cinema.

Steven Okazaki’s Mifune: The Last Samurai is an attempt to chart the legendary actor’s career as it intersects with the history of samurai cinema. Atsushi Funahashi’s Raise Your Arms and Twist! Documentary of NMB48 follows the aspiring idol stars as they go about their tightly controlled lives in one of the most controversial sectors of the Japanese entertainment industry.

Atsushi Funahashi’s Raise Your Arms and Twist! Documentary of NMB48 follows the aspiring idol stars as they go about their tightly controlled lives in one of the most controversial sectors of the Japanese entertainment industry. Start Line charts deaf filmmaker Ayako Imamura’s bicycle journey through Japan.

Start Line charts deaf filmmaker Ayako Imamura’s bicycle journey through Japan. Masked wrestling provides a ray of hope for a directionless little boy in Kohei Taniguchi’s Dynamite Wolf. Sponsored by the Dotonbori Pro Wrestling League.

Masked wrestling provides a ray of hope for a directionless little boy in Kohei Taniguchi’s Dynamite Wolf. Sponsored by the Dotonbori Pro Wrestling League. Ayako Fujimura’s charming family drama Eriko, Pretended follows its aspiring actress protagonist as she travels home for the funeral of her older sister. Having pretended to be much more successful than she really was, Eriko makes the abrupt decision to stay behind in her hometown, look after her sister’s orphaned son and take over her job as a professional mourner.

Ayako Fujimura’s charming family drama Eriko, Pretended follows its aspiring actress protagonist as she travels home for the funeral of her older sister. Having pretended to be much more successful than she really was, Eriko makes the abrupt decision to stay behind in her hometown, look after her sister’s orphaned son and take over her job as a professional mourner. Boxing trainer Asahi plans to marry his long-term girlfriend Kaori and has found a job for his close childhood friend, Hiroto, to bring him to Tokyo. Everything seems fine but Hiroto has fallen victim to a scammer and needs Asahi’s help. His first instinct is to postpone the wedding and help his friend whom he regards as a “brother” as they grew up in the same orphanage but Kaori wants her elderly grandmother to come so it needs to be as soon as possible. Going the Distance is the debut feature from director Masahiro Umeda who is expected to attend the festival in person to present his film.

Boxing trainer Asahi plans to marry his long-term girlfriend Kaori and has found a job for his close childhood friend, Hiroto, to bring him to Tokyo. Everything seems fine but Hiroto has fallen victim to a scammer and needs Asahi’s help. His first instinct is to postpone the wedding and help his friend whom he regards as a “brother” as they grew up in the same orphanage but Kaori wants her elderly grandmother to come so it needs to be as soon as possible. Going the Distance is the debut feature from director Masahiro Umeda who is expected to attend the festival in person to present his film. Tamaki and Kaori just can’t say Good/Bye in Izumi Matsuno’s nuanced drama. Despite having “broken up” the pair continue to share their apartment, marking their individual territories with coloured tape but new romantic possibilities force them to re-examine their peculiar relationship.

Tamaki and Kaori just can’t say Good/Bye in Izumi Matsuno’s nuanced drama. Despite having “broken up” the pair continue to share their apartment, marking their individual territories with coloured tape but new romantic possibilities force them to re-examine their peculiar relationship. Hirokazu Kai’s hard-hitting coming of age drama

Hirokazu Kai’s hard-hitting coming of age drama  Another technically broken up but still living together drama, Shingo Matsumura’s Love and Goodbye and Hawaii presents its heroine Rinko with a problem when she realises her ex Isamu might have found someone else.

Another technically broken up but still living together drama, Shingo Matsumura’s Love and Goodbye and Hawaii presents its heroine Rinko with a problem when she realises her ex Isamu might have found someone else. Set in Inokashira Park, Natsuki Seta’s Parks stars Ai Hashimoto as a college student who teams up with Shota Sometani and Mei Nagano to recreate the missing portions of a mysterious love song.

Set in Inokashira Park, Natsuki Seta’s Parks stars Ai Hashimoto as a college student who teams up with Shota Sometani and Mei Nagano to recreate the missing portions of a mysterious love song. The latest film from Hirobumi Watanabe, Poolsideman won the Japanese Cinema Splash Award at the Tokyo International Film Festival 2016 and focuses on the dull and lonely life of a lifeguard whose existence changes when he’s sent to a different pool.

The latest film from Hirobumi Watanabe, Poolsideman won the Japanese Cinema Splash Award at the Tokyo International Film Festival 2016 and focuses on the dull and lonely life of a lifeguard whose existence changes when he’s sent to a different pool. Yusuke Takeuchi won the best director award at the Thessaloniki International Film Festival for The Sower. Dealing with guilt and atonement, this sombre film follows Mitsuo as he returns from three years in a mental institution and bonds with his two nieces only for his fragile happiness to be disrupted by unexpected tragedy.

Yusuke Takeuchi won the best director award at the Thessaloniki International Film Festival for The Sower. Dealing with guilt and atonement, this sombre film follows Mitsuo as he returns from three years in a mental institution and bonds with his two nieces only for his fragile happiness to be disrupted by unexpected tragedy. The latest film from Yuya Ishii, The Tokyo Night Sky Is Always the Densest Shade of Blue stars Shizuka Ishibashi and Sosuke Ikematsu in an exploration of youthful alienation.

The latest film from Yuya Ishii, The Tokyo Night Sky Is Always the Densest Shade of Blue stars Shizuka Ishibashi and Sosuke Ikematsu in an exploration of youthful alienation. Daisuke Miyazaki’s Yamato California explores themes of cross cultural pollination through the story of teenager Sakura who lives near the biggest American military base in Japan and dreams of becoming a rapper. When she meets the Japanese-American daughter of her mother’s boyfriend, she finally finds an ally in an otherwise alienating place.

Daisuke Miyazaki’s Yamato California explores themes of cross cultural pollination through the story of teenager Sakura who lives near the biggest American military base in Japan and dreams of becoming a rapper. When she meets the Japanese-American daughter of her mother’s boyfriend, she finally finds an ally in an otherwise alienating place. Skip City Shorts includes four of the short films created for the Skip City International D-Cinema Festival in Saitama.

Skip City Shorts includes four of the short films created for the Skip City International D-Cinema Festival in Saitama. Six young filmmakers show different sides of Tokyo in the TKY2015 Short Film Series.

Six young filmmakers show different sides of Tokyo in the TKY2015 Short Film Series. Two shorts made by students of the Graduate School for Film and New Media at Tokyo University of the Arts.

Two shorts made by students of the Graduate School for Film and New Media at Tokyo University of the Arts.