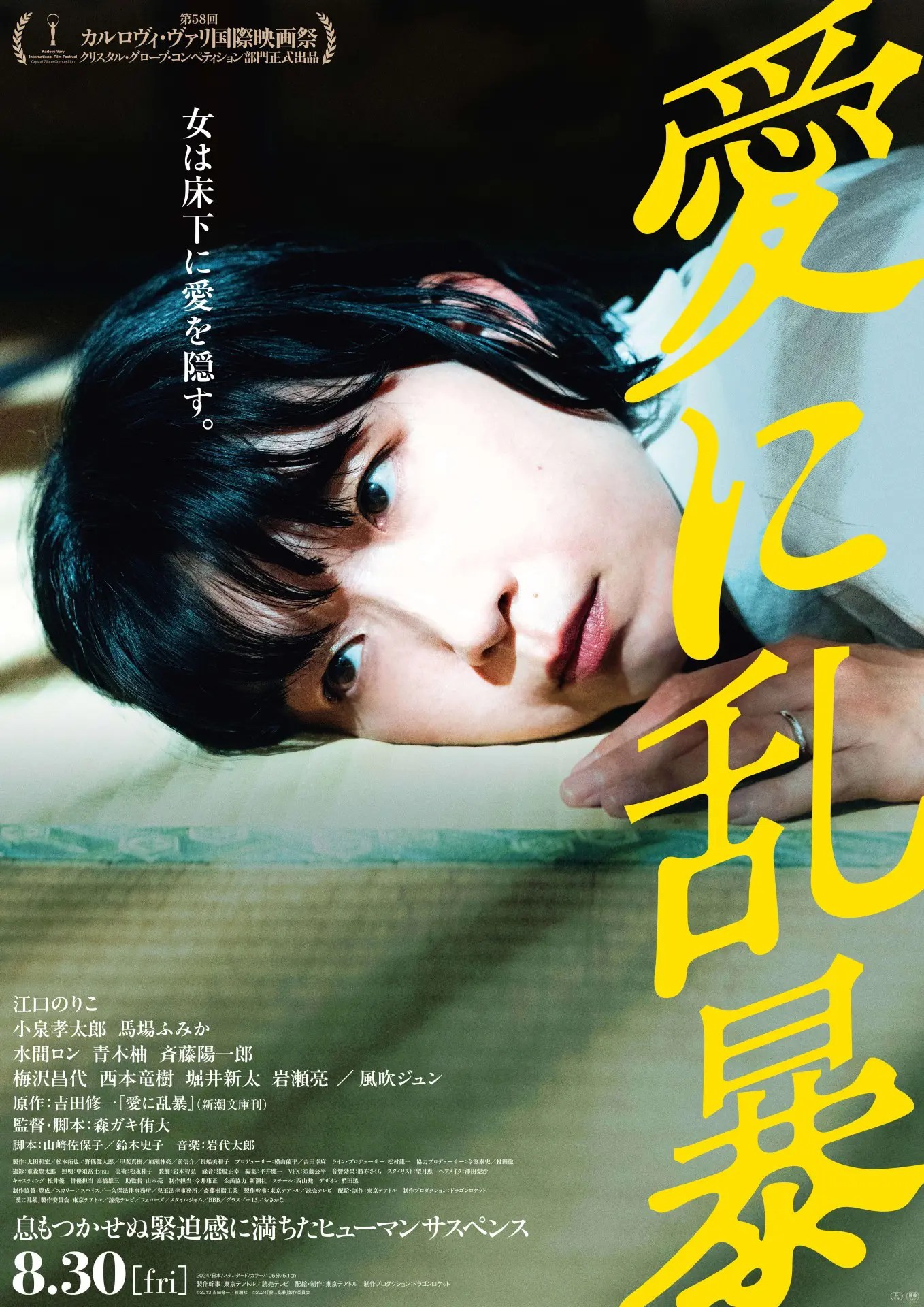

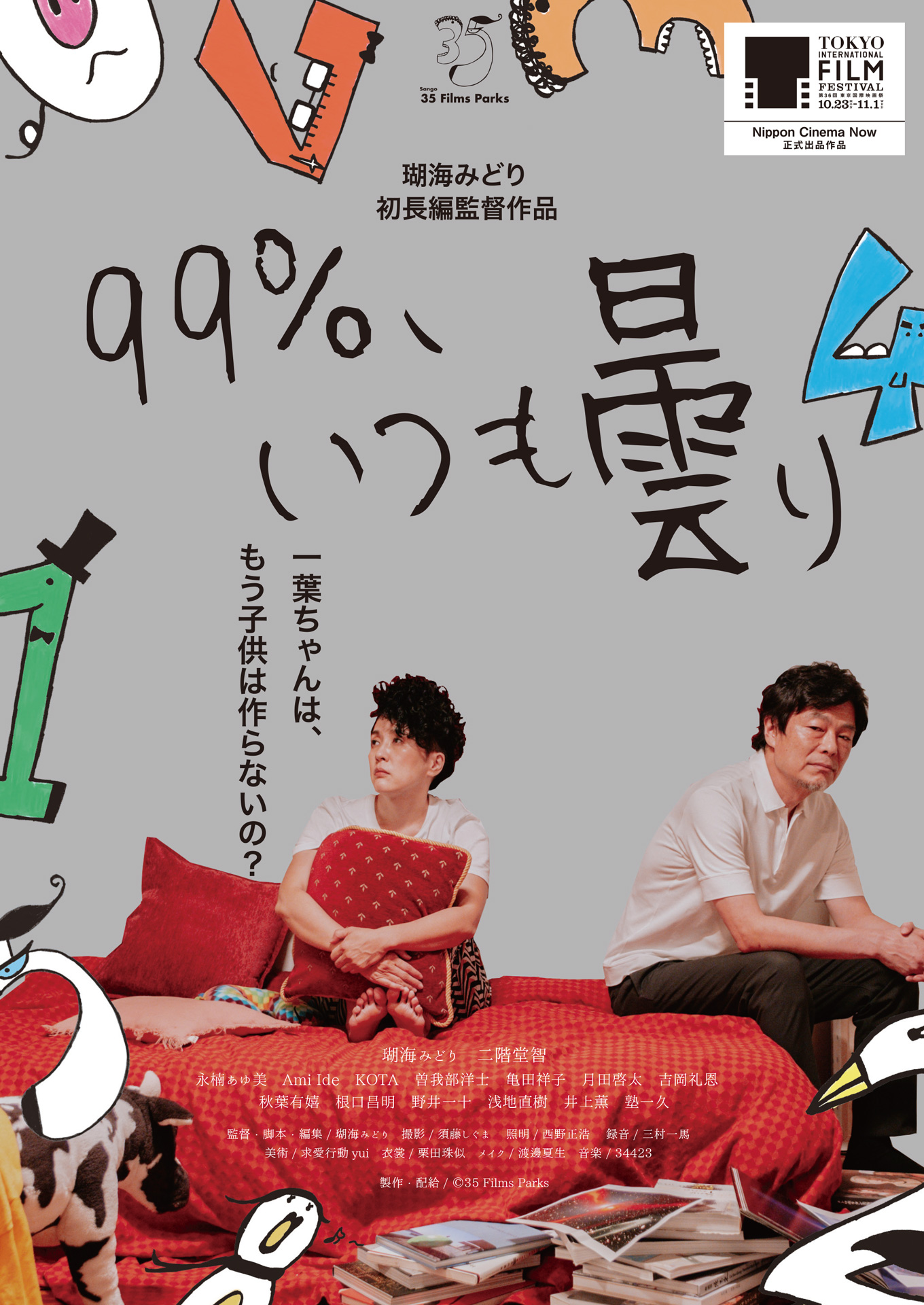

Why do some people feel themselves entitled to ask insensitive questions at emotionally delicate moments? Kazuha (Midori Sangoumi) may have a point when she calls her oblivious uncle a bully when a lays into her about having no children at the first memorial of her mother’s passing, but still his words seem to wound her and provoke a moment of crisis in what otherwise seems to be a happy and supportive marriage.

Kazuha is a very upfront person and fond of directly telling people that she thinks she has stopped menstruating so she doesn’t think she could have a child now even if she wanted one. One of the other relatives, however, suggests that her husband, Daichi (Satoshi Nikaido), may feel differently which somewhat alarms her. The questioning had made her angry and offended, not least by the implication that a woman’s life is deemed a success only through motherhood and that those who produce no children are somehow “unproductive”, but it was all the more insensitive of her uncle to bring it up given that Kazuha had suffered a miscarriage some years previously.

The miscarriage itself appears to have resulted in some lingering trauma that’s left Kazuha with ambiguous feelings towards motherhood. Having been bullied and excluded as a child because she is autistic, Kazuha is reluctant to bring a child of her own into the world in case they too are autistic and encounter the same kind of difficulties that she has faced all her life. As the film opens, she’s trying to get in touch with someone about the results of a recent job interview but getting flustered on the phone and asking what may be perceived as too many questions all in one go. She does something similar while trying to enquire at a foster agency about a clarification of their guidelines as to whether she would be eligible to adopt as an autistic woman which she fears she will not be. It just happens that no one is available to talk to her that day as they’re all at an outing leaving only a member of the admin team behind to man the desk while Kazuha repeatedly asks the same question in the hope of a response.

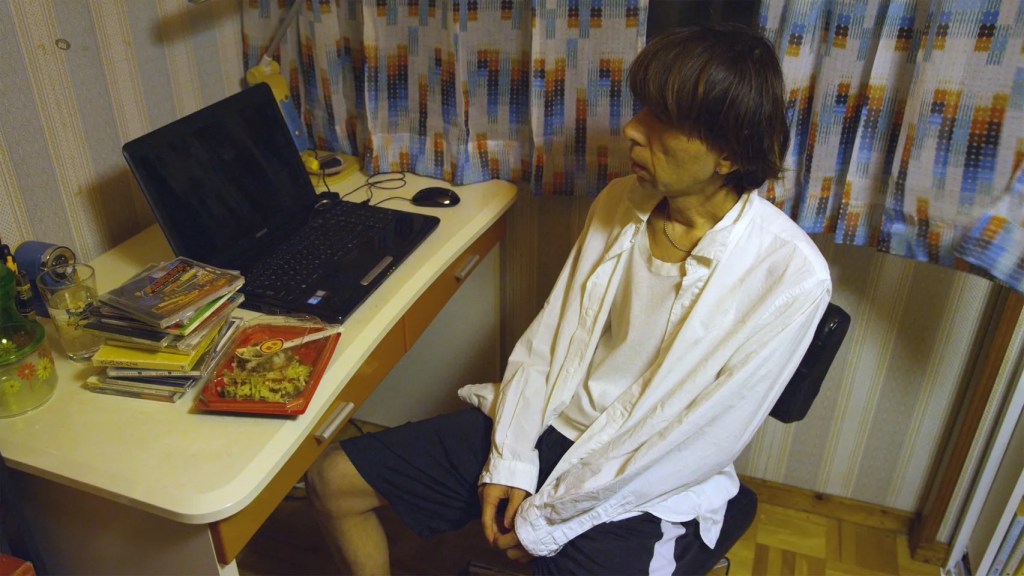

The truth is, Kazuha might have liked to raise a child but not her own while for Daichi it’s the opposite. He may still want to have a biological child but is not particularly interested in raising someone else’s. This question which has reared its head again at a critical moment immediately before it may be too late places a strain on their marriage as they contemplate a potential mismatch in their hopes and desires for the future. Daichi is reminded he has no other remaining family as his younger sister passed away of an illness some years previously and his parents are no longer around either. As he tells a younger woman at work, Kazuha is his only family while others needle them that there’ll be no one there for them in their old age should they remain childless.

Part of the issue is a lack of direct communication as Daichi talks through his relationship issues with a colleague in trying to process Kazuha’s revelation that she felt relieved after the miscarriage given her guilt and anxiety that the baby would also be autistic which is not something that had previously occurred to him nor that he particularly worried about. The film seems to hint that Daichi has the option of moving on, perhaps entering a relationship with his younger colleague, if his desire to have a biological child outweighed that to stay with Kazuha while that is not an option for Kazuha herself who is left only wondering if she should divorce him so he can do exactly that. In flashbacks, we see her reflect on some of her past behaviour and realise that she may have inadvertently hurt someone’s feelings in speaking the truth and been shunned herself because of it. Even so, she has a warm community around her who love her as she is and are in effect an extended family. The accommodation that she finds lies in fulfilling herself through art and building a relationship with her nephew while also helping and supporting those around her. It may be cloudy 99% of the time, but there’s still a glimmer of light and a radiance that surrounds Kazuha as she embraces life as she wants to live it rather than allow herself to be bullied by belligerent uncles and the spectres of social expectation.

99% Cloudy… Always screens as part of this year’s Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme.

Trailer (English subtitles)