“No one can stray from the path paved by fate.” a policewoman gasps while interrogating The Master (Gordon Lam Ka-Tung), a man whose mind was already strained even before he walked in on the murder of a woman he’d been trying to save only to end up losing to destiny. A noticeably lighter affair than his previous film Limbo, Mad Fate (命案) sees Soi Cheang (AKA Cheang Pou-soi) step into the Milky Way orbit directing a screenplay by Yau Nai-hoi produced by Johnnie To and very much bound up with the kinds of cosmic coincidences the studio is known for.

It’s Fate or maybe God that The Master is resisting, though what the difference between the two might be is never quite clear save for the implication that it’s God who is master of Fate which is otherwise without will. The Master insists that “Fate can be changed,” but he resolutely fails to do so. In the opening sequence, he’s in the middle of burying a woman, May, alive as part of a ritual to stave off a forthcoming “calamity” only he’s unable to complete it in part because of the woman’s understandable anxiety that it’s The Master who’s going to end up killing her, and in part because it starts raining which puts out the paper clothing that should have been burnt to change her fate. May runs off and climbs in a taxi home where she is accosted by a serial killer who has been targeting sex workers. The Master follows her but arrives just too late while the police later chase the killer but are unable to catch him.

The Master sees his attempts frustrated but also does not consider that the rain itself was a manifestation of Fate or sign that in the end nothing can be changed. In an effort to atone for his inability to save May, The Master ends up taking under his wing a strange young man who also stumbled on the murder by coincidence while working as a delivery driver but is fascinated rather than repulsed by the bloody scene. Obsessed with knives and killing, Siu-tung (Lokman Yeung) is already known to the policeman investigating (Berg Ng Ting-Yip) because he arrested him for killing a cat in his teens. According to The Master’s reading of his fate, Siu-tung will eventually kill someone and end up in prison for 20 years. He doesn’t much like the sound of that so he ends up going along with The Master’s zany plans to make him a nicer person and save two lives in the process.

Ironically most of The Master’s suggestions still involve Siu-tung being imprisoned in some way. To get him out of his “unlucky” flat, he rents him another place that very much feels like a prison cell and later does actually lock him up inside a shed fearing that he’s about to kill. As he explains, it can help to preemptively accept your fate so moving in somewhere that is “like” a prison can stop you going there for real, but it doesn’t do much to alleviate Siu-tung’s desire to kill and most particularly to kill the policeman who has been following him most of his life because he’s “sure” that he’s going to commit a serious crime. Repeatedly describing him as “vermin”, the policeman has no confidence that Siu-tung could “change” and thinks he’s already past redemption while The Master quite reasonably asks if it’s fair to persecute him in this way just because he happened to be born different.

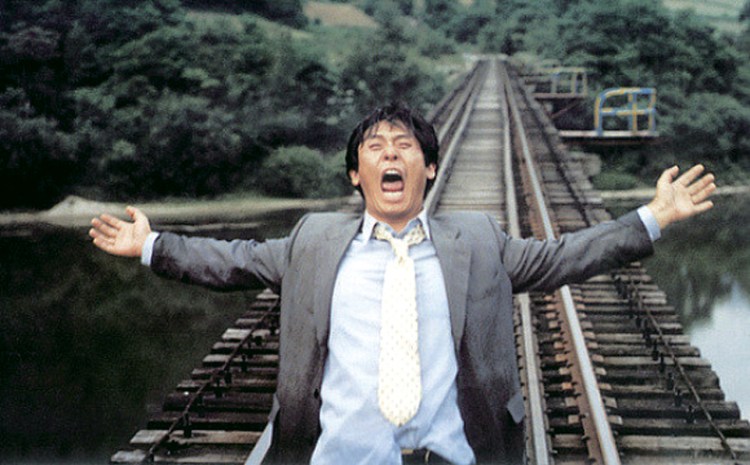

The Master’s question provokes another about free will and responsibility and if anything is really anyone’s fault if it’s all down to Fate in which case the role of the policeman becomes almost moot. He is also resisting his own fate in his intense fear of mental illness which he worries he will inherit from his parents each of whom suffered from some kind of mental distress. This fear has caused him retreat from life and it seems may have contributed another’s suicide while his divination has an otherwise manic quality as he finds himself constantly trying to outwit Fate. The two men soon find themselves in a battle with the skies, remarking that God is striking back every time they make a move to try and change their destiny.

Eventually The Master rationalises that a plant must wither before it fruits, allowing himself to slip into “madness” as means of rejecting his fate. His strategies become wilder and finally seem as if they might lead him to kill which would certainly be one way of altering Siu-tung’s destiny if ironically, while conversely something does indeed seem to change for Siu-tung who is understandably concerned by The Master’s increasingly erratic behaviour but has escaped his desire to kill. Then again, could this all not be Fate too, how would you know if you’d overcome it? As The Master comes to accept, the path maybe set but the way you walk it is up to you. Only by accepting his Fate can he free himself from it. There may be a more subversive reading to found in Cheang’s depiction of Hong Kong as a rain-soaked prison in which lives are largely defined by forces outside of their control, but he does at least suggest that his heroes have more power than they think even if it relies on a contradiction in the active choice to embrace one’s fate.

Mad Fate screens July 22 as part of this year’s New York Asian Film Festival.

Original trailer (Traditional Chinese / English subtitles)

Images: © MakerVille Company Limited and Noble Castle Asia Limited