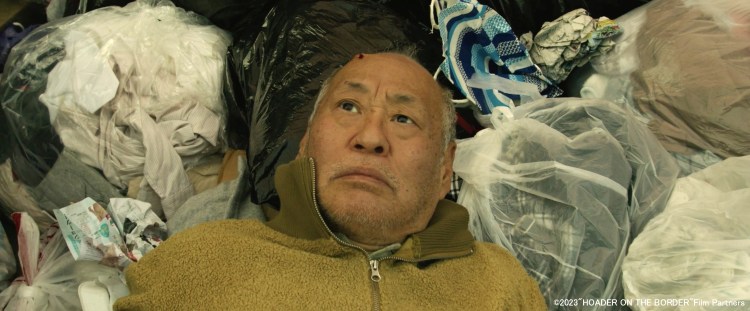

With the 2020 Olympics on the horizon, Japan began looking for ways to tidy up its image expecting an influx of foreign visitors which for obvious reasons never actually materialised. As part of this campaign, leading chains of convenience stores announced that they would stop selling pornographic magazines in order to create a more wholesome environment for children and families along with tourists who might be surprised to see such material openly displayed in an ordinary shop. Then again, given the ease of access to pornography online sales had fast been falling and the Olympics was perhaps merely a convenient excuse and effective PR opportunity to cut a product line that was no longer selling.

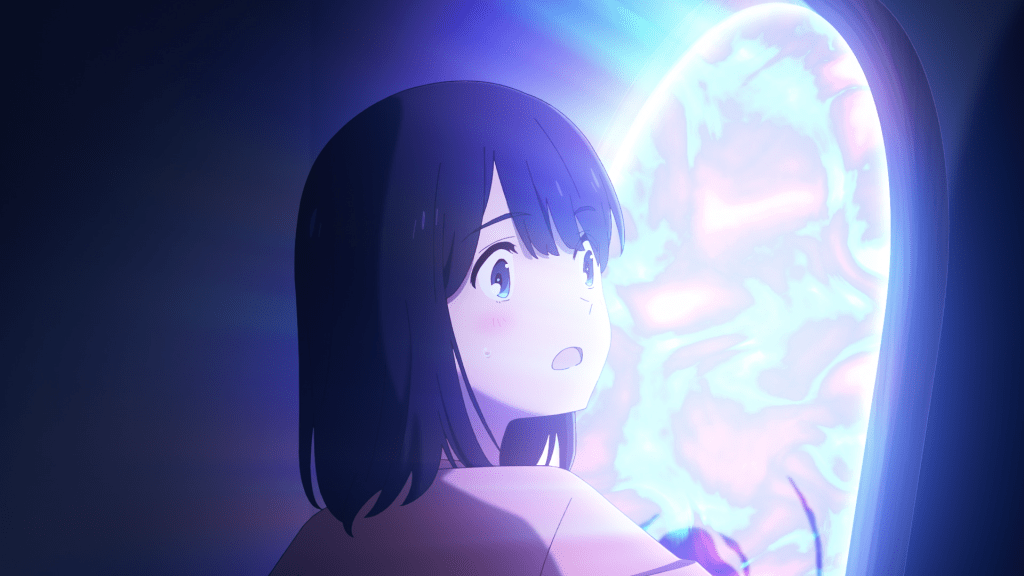

Based on actual events, Shoichi Yokoyama’s Goodbye, Bad Magazines (グッドバイ、バッドマガジンズ) explores the print industry crisis from the inside perspective of the adult magazine division at a major publisher which has just announced the closure of a long running and well respected cultural magazine, Garu. Firstly told they don’t hire right out of college, recent graduate Shiori (Kyoka Shibata) who had dreamed of working in cultural criticism is offered a job working on adult erotica and ends up taking it partly in defiance and encouraged by female editor Sawaki (Seina Kasugai) who tells that if she can make a porn mag she can make anything and be on her way to working on something more suited to her interests with a little experience under her belt.

Her first job, however, consists entirely of shredding voided pages filled with pictures of nude women which is slightly better than the veteran middle-aged man who joined with her after being transferred from Garu who is responsible for adding mosaics to the porn DVDs they give away with the magazines to ensure they conform to Japan’s strict obscenity laws. Later a mistake is made and mosaics are omitted placing the publishing company bosses at risk of arrest and the magazine closure. Aside from being one of two women in an office full of sleazy men and sex toys, Shiori’s main problem is that she struggles to get a handle on the nature of the erotic at least of the kind that has been commodified before eventually falling into a kind of automatic rhythm. “It’s easy when it does’t mean anything” she explains to sex columnist and former porn star Haru (Yura Kano) who is much franker in her expression but perhaps no more certain than Shiori when it comes to the question asked in her column, why people have sex.

Shiori asks her sympathetic colleague Mukai (Yusuke Yamada) for advice and he tells her that what’s erotic to him is relationships, but it seems his work has placed a strain on his marriage while his wife wants a baby and he has trouble separating the simple act of meaningless sex with that which has an explicit purpose such as an expression love or conceiving a child. According to Shiori’s editor Isezaki (Shinsuke Kato), the future of erotica will come from women with their boss finally agreeing to an old idea of Sawaki’s to create an adult magazine aimed at a female audience in the hope of opening a new market while handing a progressive opportunity to Sawaki and Shiori to explore female desire, but at the same time magazines are folding one after the other with major retailers canceling their orders and leaving them to ring elderly customers who’ve been subscribing for 30 years but don’t have the internet to let them know the paper edition is going out of circulation.

The editorial team have an ambivalent attitude to their work, at once proud of what they’ve achieved and viewing it as meaningless and a little embarrassing. Not much more than a few months after working there, Shiori has become a seasoned pro training a new recruit who’s just as nervous and confused as she was but offering little more guidance was than she was given while becoming ever more jaded. When handed evidence that her boss has been embezzling money, she just ignores it though perhaps realising that when he’s found out it means the end for all of them too. Like everyone else, he’d wanted to start his own publishing company but the editor who left to do just that ended up taking his own life when the business failed. Yet, on visiting a small independent family-run convince store near the sea, Shiori hears of an old man who visits specifically to buy the magazines she once published because he can’t get them anywhere else while they have steady trade from fishermen who need paper copies to takes out to sea. The message seems to be there’s a desire and a demand for print media yet, even if it’s not quite enough to satisfy the bottom line. A sympathetic and sometimes humorous take on grim tale of industrial decline, Goodbye, Bad Magazines sees its steely heroine travel from naive idealist to jaded cynic but simultaneously grants her the full freedom of her artistic expression along with solidarity with her similarly burdened colleagues.

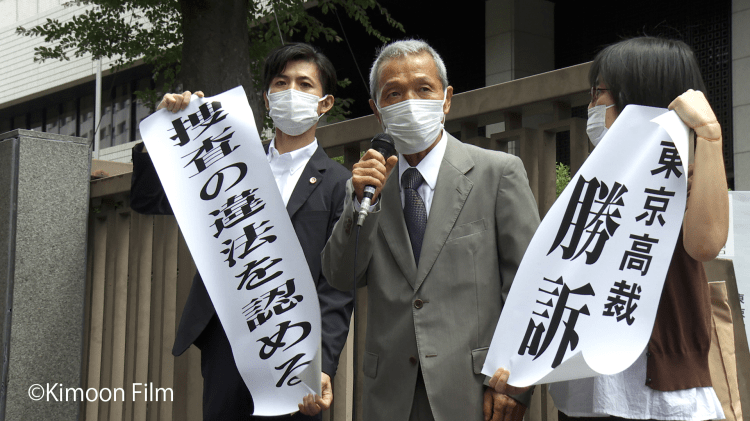

Goodbye, Bad Magazines streamed as part of the 2022 Yubari International Fantastic Film Festival.

Teaser trailer (English subtitles)