The Fantasia International Film Festival returns to cinemas for its 26th edition taking place once again in Montreal from July 14 to Aug. 3. With the full programme announced later this month here’s a look at the East Asian titles so far confirmed amid an impressive lineup of global genre cinema.

Japan

- Anime Supremacy – adaptation of the novel by Mizuki Tsujimura following three women in the anime industry.

- Baby Assassins – a pair of mismatched high school girls raised as elite assassins get swept into gangland conflict while forced to live together to learn how integrate into society in Yugo Sakamoto’s deadpan slacker comedy. Review.

- Convenience Story – comedy from Satoshi Miki in which a failed comedian encounters a mysterious woman at a convenience store.

- Girl from the Other Side – dark anime adaptation of the manga by Nagabe in which a little girl lost in the forest bonds with a mysterious beast.

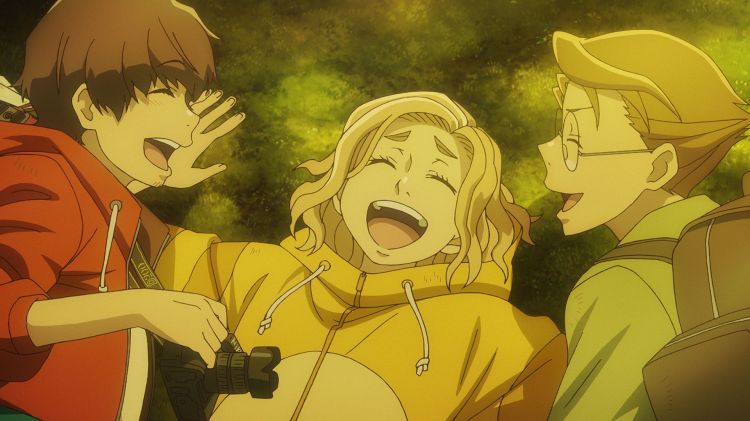

- Goodbye, Donglees! – animation in which two boys head off into the woods after being falsely accused of starting a fire.

- Just Remembering – bittersweet love story from Daigo Matsui inspired by Jim Jarmusch’s Night on Earth.

- Inu-Oh – a blind Biwa player and a cursed young man exorcise the spirits of the Heike through musical expression in Masaaki Yuasa’s stunning prog rock anime. Review.

- Kappei – quirky comedy in which a collection of adults raised for an apocalypse that never happened must try to live normal lives.

- Missing – darkly comic thriller in which a young girl searches for her father who went missing after saying he was going to claim the bounty on a serial killer he spotted in town.

- The Mole Song: Final – undercover cop Reiji finds himself increasingly conflicted in his mission to take down Todoroki in the final instalment of the comedic trilogy. Review.

- The Pass: Last Days of the Samurai – holding fast to samurai ideals a progressive retainer realises his era is at an end in Takashi Koizumi’s homage to classic samurai cinema. Review.

- Popran – a self-involved CEO gets a course correction when his genitals suddenly decide to leave him in Shinichiro Ueda’s surreal morality tale. Review.

- Shari – experimental film in which a red monster invades the ordinary life of a snowy town.

- Shin Ultraman – big budget adaptation of the classic tokusatsu series directed Shinji Higuchi with a screenplay by Hideaki Anno.

- What to Do with Dead Kaiju – satire from Satoshi Miki in which bureaucrats must try to decide how to dispose of the corpse of a defeated kaiju.

Korea

- Chun Tae-il: The Flame That Lives On – animated biopic of labour activist Chun Tae-il who self-immolated in protest of Korea’s exploitative employment environment.

- Heaven: To the Land of Happiness – a chronically ill thief and a “poetic fugitive” find themselves on the run from a “philosophical gangster” in Im Sang-soo’s playful existential drama. Review.

- Next Door – drama inspired by the life of Kim Dae-jung in which the leader of the opposition tries to battle a government which has installed a surveillance team in the house next door.

- On the Line – a former policeman gets back on the case when his wife is targeted by telephone scammers in Kim Gok & Kim Sun’s steely action thriller. Review.

- The Roundup – sequel to The Outlaws starring Ma Dong-seok as a detective who pursues a vicious killer all the way to Vietnam.

- Stellar – dramedy in which a man comes to understand his father while on the run in his beat up Hyundae Stellar.

Philippines

- Whether the Weather is Fine – Philippine drama in which a mother and son search for missing loved ones in the aftermath of disaster.

Thailand

- Fast and Feel Love – drama in which a world champion sport stacker has to learn to look after himself after his girlfriend dumps him.

- One for the Road – a New York club owner returns to Thailand on learning that his friend has been diagnosed with terminal cancer.

The Fantasia International Film Festival runs in Montreal, Canada, July 14 to Aug 3. Full details for all the films are available via the the official website, and you can also keep up with all the latest news via the festival’s official Facebook page, Twitter account, Instagram, and Vimeo channels.