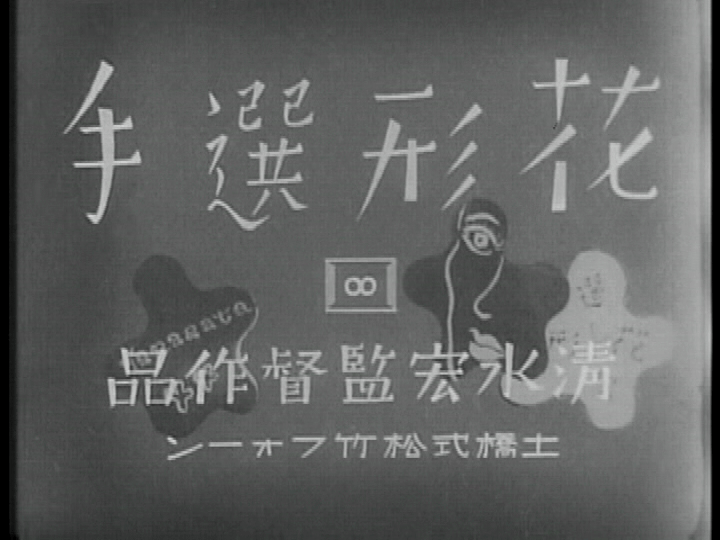

Japan in 1937 – film is propaganda, yet Hiroshi Shimizu once again does what he needs to do in managing to pay mere lip service to his studio’s aims. Star Athlete (花形選手, Hanagata senshu) is, ostensibly, a college comedy in which a group of university students debate the merits of physical vs cerebral strength and the place of the individual within the group yet it resolutely refuses to give in to the prevailing narrative of the day that those who cannot or will not conform must be left behind.

Japan in 1937 – film is propaganda, yet Hiroshi Shimizu once again does what he needs to do in managing to pay mere lip service to his studio’s aims. Star Athlete (花形選手, Hanagata senshu) is, ostensibly, a college comedy in which a group of university students debate the merits of physical vs cerebral strength and the place of the individual within the group yet it resolutely refuses to give in to the prevailing narrative of the day that those who cannot or will not conform must be left behind.

Seki (Shuji Sano) is the star of the athletics club and shares a friendly rivalry with his best friend Tani (Chishu Ryu). Tani likes to train relentlessly but Seki thinks that winning is the most important thing and perhaps it’s better to be adequately rested to compete at full strength. While the two of them are arguing about the best way to be productive, their two friends prefer to settle the matter by sleeping. The bulk of the action takes place as the guys take part in a military training exercise which takes the form of a long country march requiring an overnight stay in a distant town. The interpersonal drama deepens as Seki develops an interest in a local girl who may or may not be a prostitute, casting him into disrepute with his teammates though he’s ultimately saved by Tani (in an unconventional way).

Far from the austere and didactic nature of many similarly themed films, Shimizu allows his work to remain playful and even a little slapsticky towards the end. These are boys playing at war, splashing through lakes and waving guns around but it’s all fun to them. Their NCO maybe taking things much more seriously but none of these men is actively anticipating that this is a real experience meant to prepare them for the battlefield, just a kind of fun camping trip that they’re obliged to go on as part of their studies. The second half of the trip in which the NCO comes up with a scenario that they’re attempting to rout a number of survivors from a previous battle can’t help but seem ridiculous when their “enemies” are just local townspeople trying to go about their regular business but now frightened thinking the students are out for revenge for ruining their fun the night before.

That said, the boys do pick up some female interest in the form of a gaggle of young women who are all very taken with their fine uniforms. The women continue to track them on their way with a little of their interest returned from the young men (who are forbidden to fraternise). Singing propaganda songs as they go, the troupe also inspires a group of young boys hanging about in the village who try to join in, taken in by Tani’s mocking chant of “winning is the best” and forming a mini column of their own. After this (retrospectively) worrying development which points out the easy spread of patriotic militarism, the most overtly pro-military segment comes right at the end with an odd kind of celebration for one of the men who has received his draft card and will presumably be heading out to Manchuria and a situation which will have little in common with the pleasant boy scout antics of the previous few days.

Physical prowess is the ultimate social marker and Seki leads the pack yet, when he gets himself into trouble, his NCO reminds him that “even stars must obey the rules” and threatens to expel him though relents after Tani takes the opportunity to offer a long overdue sock to the jaw which repairs the boys’ friendship and prevents Seki being thrown out of the group. Seki’s individuality is well and truly squashed in favour of group unity though Shimizu spares us a little of his time to also point out the sorrow of the young woman from the inn, left entirely alone, excluded from all groups as the students leave.

Employing the same ghostly, elliptical technique of forward marching dissolves to advance along the roadway that proved so effective during Mr. Thank you, Shimizu makes great use of location shooting to follow the young men on the march. Though the final scene is once again a humorous one as the two sleepyheaded lazybones attempt to keep pace with the front runners, the preceding scene is another of Shimizu’s favourite sequences of people walking along a road and disappearing below a hill, singing as they go. However, rather than the cheerful, hopeful atmosphere this conveyed in Shiinomi School there is a feeling of foreboding in watching these uniformed boys march away singing, never to reappear. Shimizu casts the “training exercise” as a silly adolescent game in which women and children are allowed to mockingly join in, but he also undercuts the irony with a subtle layer of discomfort that speaks of a disquiet about the road that these young men are marching on, headlong towards an uncertain future.

Perhaps best known for his work with children, Hiroshi Shimizu changes tack for his 1937 adaptation of the oft filmed Ozaki Koyo short story The Golden Demon (金色夜叉, Konjiki Yasha) which is notable for featuring none at all – of the literal kind at least. A story of love and money, The Golden Demon has many questions to ask not least among them who is the most selfish when it comes to a frustrated romance.

Perhaps best known for his work with children, Hiroshi Shimizu changes tack for his 1937 adaptation of the oft filmed Ozaki Koyo short story The Golden Demon (金色夜叉, Konjiki Yasha) which is notable for featuring none at all – of the literal kind at least. A story of love and money, The Golden Demon has many questions to ask not least among them who is the most selfish when it comes to a frustrated romance. Sad stories of single mothers forced to work in the world of low entertainment are not exactly rare in pre-war Japanese cinema yet Hiroshi Shimizu’s 1937 entry, Forget Love For Now (Koi mo Wasurete) , puts his on own characteristic spin on things by looking at the situation through the eyes of the young son, Haru (Jun Yokoyama). Frustrated by both social and economic woes, little Haru’s life is blighted by loneliness and resentment culminating in tragedy for all.

Sad stories of single mothers forced to work in the world of low entertainment are not exactly rare in pre-war Japanese cinema yet Hiroshi Shimizu’s 1937 entry, Forget Love For Now (Koi mo Wasurete) , puts his on own characteristic spin on things by looking at the situation through the eyes of the young son, Haru (Jun Yokoyama). Frustrated by both social and economic woes, little Haru’s life is blighted by loneliness and resentment culminating in tragedy for all. Like many other areas of the world in the first half of the 20th century, Japan also found itself at a dividing line of political thought with militarism on the rise from the late 1920s. Despite the onward march of right-wing ideology, the left was not necessarily silent. Ironically, the then voiceless cinema was able to speak for those who were its greatest consumers as an accidental genre was born detailing the everyday hardships faced by those at the bottom end of the ladder. These “proletarian films” or “tendency films” (keiko eiga) were increasingly suppressed as time went on yet, in contrast to the more politically overt cinema of the independent Proletarian Film League of Japan, continued to be produced by mainstream studios. Long thought lost, Shigeyoshi Suzuki’s What Made Her Do It? (何が彼女をそうさせたか, Nani ga Kanojo wo Sousaseta ka) was a major hit on its original release with some press reports even claiming the film provoked riots when audiences were passionately moved by the heroine’s tragic descent into madness and arson after suffering countless cruelties in an unfeeling world.

Like many other areas of the world in the first half of the 20th century, Japan also found itself at a dividing line of political thought with militarism on the rise from the late 1920s. Despite the onward march of right-wing ideology, the left was not necessarily silent. Ironically, the then voiceless cinema was able to speak for those who were its greatest consumers as an accidental genre was born detailing the everyday hardships faced by those at the bottom end of the ladder. These “proletarian films” or “tendency films” (keiko eiga) were increasingly suppressed as time went on yet, in contrast to the more politically overt cinema of the independent Proletarian Film League of Japan, continued to be produced by mainstream studios. Long thought lost, Shigeyoshi Suzuki’s What Made Her Do It? (何が彼女をそうさせたか, Nani ga Kanojo wo Sousaseta ka) was a major hit on its original release with some press reports even claiming the film provoked riots when audiences were passionately moved by the heroine’s tragic descent into madness and arson after suffering countless cruelties in an unfeeling world.

The second of the only three extant films directed by Sadao Yamanaka in his intense yet brief career, Kochiyama Soshun (河内山宗俊, oddly retitled “Preist of Darkness” in its English language release) is not as obviously comic or as desperately bleak as the other two but falls somewhere in between with its meandering tale of a stolen (ceremonial) knife which precedes to carve a deep wound into the lives of everyone connected with it. Once again taking place within the realm of the jidaigeki, Kochiyama Soshun focuses more tightly on the lives of the dispossessed, downtrodden, and criminal who invoke their own downfall by attempting to repurpose and misuse the samurai’s symbol of his power, only to find it hollow and void of protection.

The second of the only three extant films directed by Sadao Yamanaka in his intense yet brief career, Kochiyama Soshun (河内山宗俊, oddly retitled “Preist of Darkness” in its English language release) is not as obviously comic or as desperately bleak as the other two but falls somewhere in between with its meandering tale of a stolen (ceremonial) knife which precedes to carve a deep wound into the lives of everyone connected with it. Once again taking place within the realm of the jidaigeki, Kochiyama Soshun focuses more tightly on the lives of the dispossessed, downtrodden, and criminal who invoke their own downfall by attempting to repurpose and misuse the samurai’s symbol of his power, only to find it hollow and void of protection. Sadao Yamanaka had a meteoric rise in the film industry completing 26 films between 1932 and 1938 after joining the Makino company at only 20 years old. Alongside such masters to be as Ozu, Naruse, and Mizoguchi, Yamanaka became one of the shining lights of the early Japanese cinematic world. Unfortunately, this light went out when Yamanaka was drafted into the army and sent on the Manchurian campaign where he unfortunately died in a field hospital at only 28 years old. Despite the vast respect of his peers, only three of Yamanaka’s 26 films have survived. Tange Sazen: The Million Ryo Pot (丹下左膳余話 百萬両の壺, Tange Sazen Yowa: Hyakuman Ryo no Tsubo) is the earliest of these and though a light hearted effort displays his trademark down to earth humanity.

Sadao Yamanaka had a meteoric rise in the film industry completing 26 films between 1932 and 1938 after joining the Makino company at only 20 years old. Alongside such masters to be as Ozu, Naruse, and Mizoguchi, Yamanaka became one of the shining lights of the early Japanese cinematic world. Unfortunately, this light went out when Yamanaka was drafted into the army and sent on the Manchurian campaign where he unfortunately died in a field hospital at only 28 years old. Despite the vast respect of his peers, only three of Yamanaka’s 26 films have survived. Tange Sazen: The Million Ryo Pot (丹下左膳余話 百萬両の壺, Tange Sazen Yowa: Hyakuman Ryo no Tsubo) is the earliest of these and though a light hearted effort displays his trademark down to earth humanity. Naruse’s final silent movie coincided with his last film made at Shochiku where his down to earth artistry failed to earn him the kind of acclaim that the big hitters like Ozu found with studio head Shiro Kido. Street Without End (限りなき舗道, Kagirinaki Hodo) was a project no one wanted. Adapted from a popular newspaper serial about the life of a modern tea girl in contemporary Tokyo, it smacked a little of low rent melodrama but after being given the firm promise that after churning out this populist piece he could have free reign on his next project, Naruse accepted the compromise. Unfortunately, the agreement was not honoured and Naruse hightailed it to Photo Chemical Laboratories (later Toho) where he spent the next thirty years.

Naruse’s final silent movie coincided with his last film made at Shochiku where his down to earth artistry failed to earn him the kind of acclaim that the big hitters like Ozu found with studio head Shiro Kido. Street Without End (限りなき舗道, Kagirinaki Hodo) was a project no one wanted. Adapted from a popular newspaper serial about the life of a modern tea girl in contemporary Tokyo, it smacked a little of low rent melodrama but after being given the firm promise that after churning out this populist piece he could have free reign on his next project, Naruse accepted the compromise. Unfortunately, the agreement was not honoured and Naruse hightailed it to Photo Chemical Laboratories (later Toho) where he spent the next thirty years. Following on from

Following on from  Naruse’s critical breakthrough came in 1933 with the intriguingly titled Apart From You (君と別れて, Kimi to Wakarete) which made it into the top ten list of the prestigious film magazine Kinema Junpo at the end of the year. The themes are undoubtedly familiar and would come dominate much of Naruse’s later output as he sets out to detail the lives of two ordinary geisha and their struggles with their often unpleasant line of work, society at large, and with their own families.

Naruse’s critical breakthrough came in 1933 with the intriguingly titled Apart From You (君と別れて, Kimi to Wakarete) which made it into the top ten list of the prestigious film magazine Kinema Junpo at the end of the year. The themes are undoubtedly familiar and would come dominate much of Naruse’s later output as he sets out to detail the lives of two ordinary geisha and their struggles with their often unpleasant line of work, society at large, and with their own families.