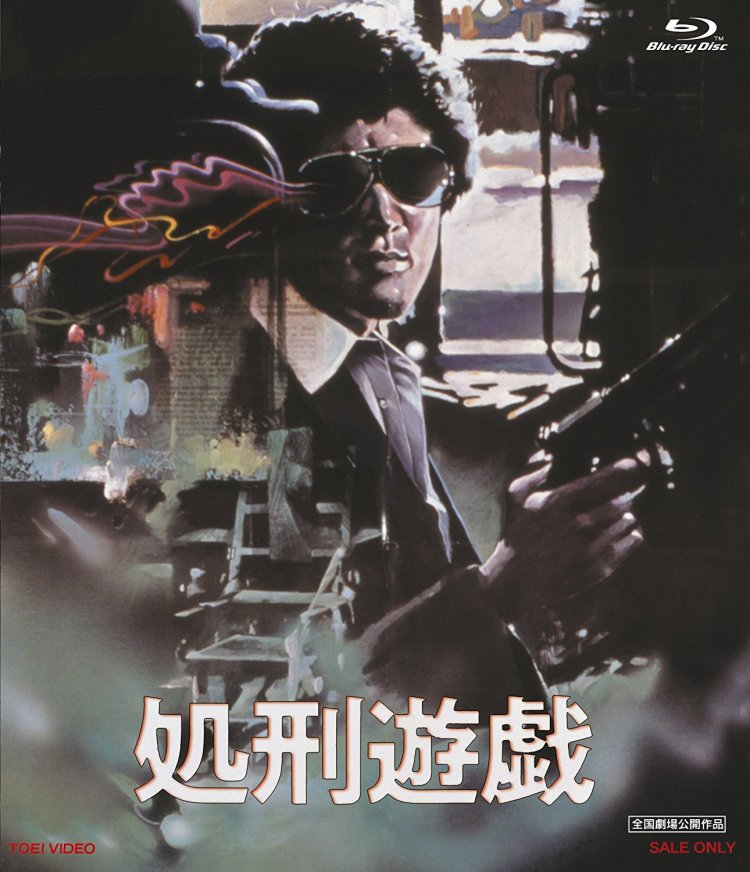

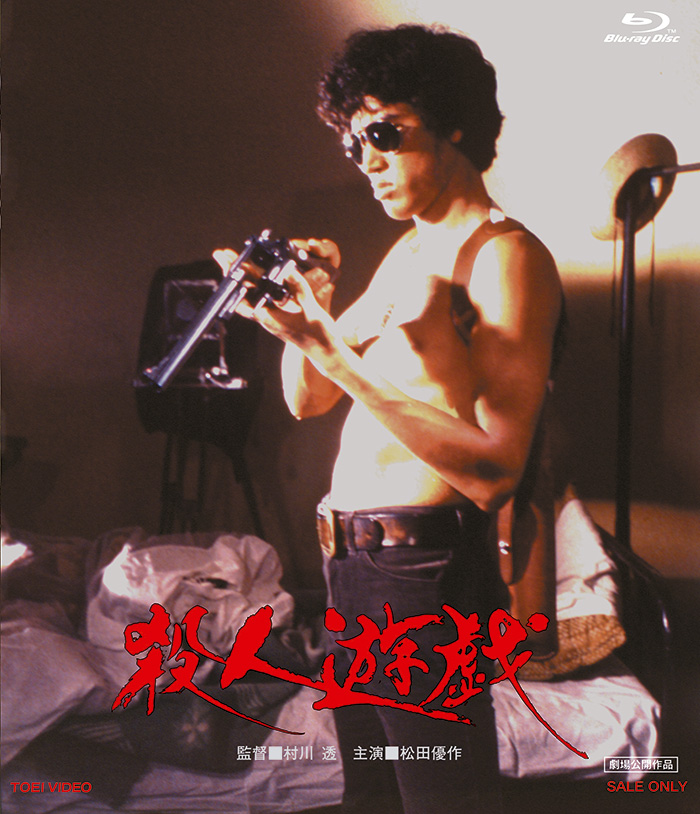

A year on from The Killing Game, Narumi (Yusaku Matsuda) has returned to his old profession, now branded The Execution Game (処刑遊戯, Shokei yugi). Like Killing, Execution is a variation on the themes of The Most Dangerous Game – conspiracy, betrayal, double cross, and corruption, but all in all Narumi’s world hasn’t changed very much even as he seems to become ever more dead to himself as he walks the dark city streets, trench coat, sunshades, and cigarettes blocking out its remaining light and warmth.

A year on from The Killing Game, Narumi (Yusaku Matsuda) has returned to his old profession, now branded The Execution Game (処刑遊戯, Shokei yugi). Like Killing, Execution is a variation on the themes of The Most Dangerous Game – conspiracy, betrayal, double cross, and corruption, but all in all Narumi’s world hasn’t changed very much even as he seems to become ever more dead to himself as he walks the dark city streets, trench coat, sunshades, and cigarettes blocking out its remaining light and warmth.

Unlike Dangerous or Killing, Execution opens indoors as Narumi lies half awake in an empty, dark and dirty room. Coming to, he remembers a girl and a car followed by a bump on the head but not much else. His attempt to escape lands him suspended from the ceiling in another room that’s shifted from green to red, but as he will shortly find out this is all part of a weird job interview. The shady guys who kidnapped him simply wanted to test his skills and, finding them adequate, now intend to force him to take their assignment to knock off their old hitman because he’s become too “weird” and they don’t need him around anymore. Narumi’s not too happy about any of this but then he does quite like getting paid. As usual, his first job leads to a second which has some wider implications involving international espionage.

Following his previous experiences, Narumi’s personal life seems to be less of a disaster but then that might be precisely because he has no personal life. In contrast to his increasingly detached persona, Execution marks the first time in the series in which he appears to enter into an entirely consensual relationship with a woman whom he genuinely seems to care about. Unfortunately she is not all she seems and, in a sense, betrays him. Nevertheless, even if the relationship is “fake” or at least part of an ongoing operation to trap Narumi into working for people he might otherwise avoid, it does provoke a kind of opening up as far as Narumi’s past is concerned. His seaside boyhood (perhaps why he chose the riverside town for his “retirement” in Killing) and longing for the ocean provide a clue to his restless heart as the sound of waves becomes a repeated cue signalling Narumi’s hidden emotional ebb and flow.

Yet externally he’s even more silent and closed off than before. Narumi’s hitman credentials have never been stronger and he pulls of his hits with steely precision. He is fearless in the face of danger, wading into the bloody finale with barely repressed fury, making sure none of these mass manipulators will survive their attempt to turn him into a disposable tool to be destroyed after use. Once again his second job provides him with a motive to get back in shape, making space for yet another training montage, but this time the mirrors are about more than vanity. Narumi’s world has always been dark, born of night and chaos, yet he remains the only point of order despite the illicit, dangerous, and immoral nature of his occupation.

Narumi’s interaction with the young woman who runs the watch repair shop where he tries to get his pocket watched fixed is perhaps the best indicator of his progress over the series. The girl is first very taken with his watch which is rare and expensive, but is also later captivated by his cool exterior. She flirts with him, subtly, but Narumi deflects it. His demeanour towards her becomes paternal, finally he warns her against chasing every shady guy she meets – she doesn’t see the danger. This Narumi, in contrast to his rather pathetic existence in the first two films, is of the world but not in it. He sees himself as occupying a very different space than this young girl, and is resigned to walking a lonely road. The Execution Game is an apt way to describe his life story, yet even as something of him dies something else rises in his self imposed exile and desire for both self preservation and old fashioned nobility even within the bounds of his world weary cynicism.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

Sadao Nakajima had made his name with Toei’s particular brand of violent action movie, but by the early seventies, the classic yakuza flick was going out of fashion. Datsugoku Hiroshima Satsujinshu (脱獄広島殺人囚, AKA The Rapacious Jailbreaker) follows in the wake of seminal genre buster,

Sadao Nakajima had made his name with Toei’s particular brand of violent action movie, but by the early seventies, the classic yakuza flick was going out of fashion. Datsugoku Hiroshima Satsujinshu (脱獄広島殺人囚, AKA The Rapacious Jailbreaker) follows in the wake of seminal genre buster,  Robbing a bank is harder than it looks but if it does all go very wrong, escaping by bus is not an ideal solution. Sadao Nakajima is best known for his gritty yakuza movies but Kurutta Yaju ( 狂った野獣, Crazed Beast/Savage Beast Goes Mad) takes him in a slightly different direction with its strangely comic tale of bus hijacking, counter hijacking, inept police, and fretting mothers. If it can go wrong it will go wrong, and for a busload of people in Kyoto one sunny morning, it’s going to be a very strange day indeed.

Robbing a bank is harder than it looks but if it does all go very wrong, escaping by bus is not an ideal solution. Sadao Nakajima is best known for his gritty yakuza movies but Kurutta Yaju ( 狂った野獣, Crazed Beast/Savage Beast Goes Mad) takes him in a slightly different direction with its strangely comic tale of bus hijacking, counter hijacking, inept police, and fretting mothers. If it can go wrong it will go wrong, and for a busload of people in Kyoto one sunny morning, it’s going to be a very strange day indeed. All things considered, a live pig is a rather insensitive gift to present to your local police station, though any gift at all might be considered in appropriate even if offered by a well meaning colleague keen to help out when a horrific murder may be connected to his missing person case. By 1977 Kinji Fukasaku had made a name for himself through the wildly successful “jitsuroku” or “true record” genre of yakuza movies kickstarted by his own

All things considered, a live pig is a rather insensitive gift to present to your local police station, though any gift at all might be considered in appropriate even if offered by a well meaning colleague keen to help out when a horrific murder may be connected to his missing person case. By 1977 Kinji Fukasaku had made a name for himself through the wildly successful “jitsuroku” or “true record” genre of yakuza movies kickstarted by his own  Cops vs Thugs – a battle fraught with friendly fire. Arising from additional research conducted for the first

Cops vs Thugs – a battle fraught with friendly fire. Arising from additional research conducted for the first  Universal’s Monster series might have a lot to answer for in creating a cinematic canon of ambiguous “heroes” who are by turns both worthy of pity and the embodiment of somehow unnatural evil. Despite the enduring popularity of Dracula, Frankenstein (dropping his “monster” monicker and acceding to his master’s name even if not quite his identity), and even The Mummy, the Wolf Man has, appropriately enough, remained a shadowy figure relegated to a substratum of second-rate classics. Kazuhiko Yamaguchi’s Wolf Guy (ウルフガイ 燃えよ狼男, Wolf Guy: Moero Okami Otoko, AKA Wolfguy: Enraged Lycanthrope) is no exception to this rule and in any case pays little more than lip service to werewolf lore. An adaptation of a popular manga, Wolf Guy is one among dozens of disposable B-movies starring action hero Sonny Chiba which have languished in obscurity save for the attentions of dedicated superfans, but sure as a full moon its time has come again.

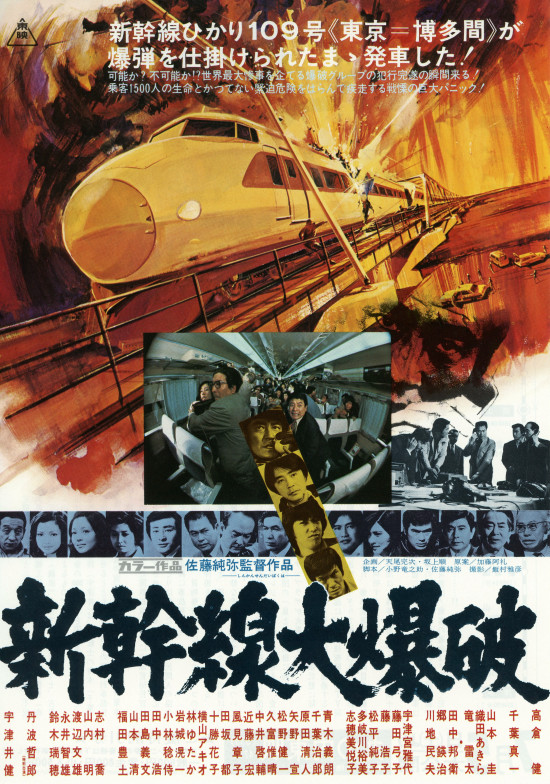

Universal’s Monster series might have a lot to answer for in creating a cinematic canon of ambiguous “heroes” who are by turns both worthy of pity and the embodiment of somehow unnatural evil. Despite the enduring popularity of Dracula, Frankenstein (dropping his “monster” monicker and acceding to his master’s name even if not quite his identity), and even The Mummy, the Wolf Man has, appropriately enough, remained a shadowy figure relegated to a substratum of second-rate classics. Kazuhiko Yamaguchi’s Wolf Guy (ウルフガイ 燃えよ狼男, Wolf Guy: Moero Okami Otoko, AKA Wolfguy: Enraged Lycanthrope) is no exception to this rule and in any case pays little more than lip service to werewolf lore. An adaptation of a popular manga, Wolf Guy is one among dozens of disposable B-movies starring action hero Sonny Chiba which have languished in obscurity save for the attentions of dedicated superfans, but sure as a full moon its time has come again. For one reason or another, the 1970s gave rise to a wave of disaster movies as Earthquakes devastated cities, high rise buildings caught fire, and ocean liners capsized. Japan wanted in on the action and so set about constructing its own culturally specific crisis movie. The central idea behind The Bullet Train (新幹線大爆破, Shinkansen Daibakuha) may well sound familiar as it was reappropriated for the 1994 smash hit and ongoing pop culture phenomenon Speed, but even if de Bont’s finely tuned rollercoaster was not exactly devoid of subversive political commentary The Bullet Train takes things one step further.

For one reason or another, the 1970s gave rise to a wave of disaster movies as Earthquakes devastated cities, high rise buildings caught fire, and ocean liners capsized. Japan wanted in on the action and so set about constructing its own culturally specific crisis movie. The central idea behind The Bullet Train (新幹線大爆破, Shinkansen Daibakuha) may well sound familiar as it was reappropriated for the 1994 smash hit and ongoing pop culture phenomenon Speed, but even if de Bont’s finely tuned rollercoaster was not exactly devoid of subversive political commentary The Bullet Train takes things one step further. Edogawa Rampo (a clever allusion to master of the gothic and detective story pioneer Edgar Allan Poe) has provided ample inspiration for many Japanese films from

Edogawa Rampo (a clever allusion to master of the gothic and detective story pioneer Edgar Allan Poe) has provided ample inspiration for many Japanese films from

About half way through Lino Brocka’s masterpiece of Philippine cinema Manila in the Claws of Light (Maynila, sa mga Kuko ng Liwanag), the hero, Julio (Bembol Roco), sits watching the window where he thinks the woman he loves may be being held prisoner as a trio of guitar players strums out The Impossible Dream, unwittingly narrating his entire story. Julio is no Don Quixote but he has his own Dulcinea and, as the song says, without question or pause he is ready to march into hell for the heavenly cause of rescuing her from clutches of this cruel city. Not quite content to love pure and chaste from afar, Julio plays Orpheus descending into the underworld, plunged into a strange odyssey through a harsh and indifferent world driven by mutual exploitation and the expectation of violence.

About half way through Lino Brocka’s masterpiece of Philippine cinema Manila in the Claws of Light (Maynila, sa mga Kuko ng Liwanag), the hero, Julio (Bembol Roco), sits watching the window where he thinks the woman he loves may be being held prisoner as a trio of guitar players strums out The Impossible Dream, unwittingly narrating his entire story. Julio is no Don Quixote but he has his own Dulcinea and, as the song says, without question or pause he is ready to march into hell for the heavenly cause of rescuing her from clutches of this cruel city. Not quite content to love pure and chaste from afar, Julio plays Orpheus descending into the underworld, plunged into a strange odyssey through a harsh and indifferent world driven by mutual exploitation and the expectation of violence.