You know how it is. You work hard, make sacrifices and expect the system to reward you with advancement. The system, however, has its biases and none of them are in your favour. Watching the less well equipped leapfrog ahead by virtue of their privileges, it’s difficult not to lose heart. Asakura (Yusaku Matsuda), the (anti) hero of Toru Murakawa’s Resurrection of Golden Wolf (蘇る金狼, Yomigaeru Kinro), has had about all he can take of the dead end accountancy job he’s supposedly lucky to have despite his high school level education (even if it is topped up with night school qualifications). Resentful at the way the odds are always stacked against him, Asakura decides to take his revenge but quickly finds himself becoming embroiled in a series of ongoing corporate scandals.

You know how it is. You work hard, make sacrifices and expect the system to reward you with advancement. The system, however, has its biases and none of them are in your favour. Watching the less well equipped leapfrog ahead by virtue of their privileges, it’s difficult not to lose heart. Asakura (Yusaku Matsuda), the (anti) hero of Toru Murakawa’s Resurrection of Golden Wolf (蘇る金狼, Yomigaeru Kinro), has had about all he can take of the dead end accountancy job he’s supposedly lucky to have despite his high school level education (even if it is topped up with night school qualifications). Resentful at the way the odds are always stacked against him, Asakura decides to take his revenge but quickly finds himself becoming embroiled in a series of ongoing corporate scandals.

Orchestrating a perfectly planned robbery on his own firm in which Asakura deprives his employers of a large amount money, he’s feeling kind of smug only to realise that the bank had a backup plan. The serial numbers of all of the missing money have been recorded meaning he can’t risk spending any of it. Accordingly he decides the “safest” thing to do is exchange the problematic currency for the equivalent in heroine. His plan doesn’t stop there, however. He also knows the big wigs at the top are engaged in a high level embezzlement scam and seduces his boss’ mistress, Kyoko (Jun Fubuki), for the inside track. Asakura is not the only game in town as another detective, Sakurai (Sonny Chiba), is blackmailing some of the other bosses over their extra-marital activities. Playing both sides off against each other, Asakura thinks he has the upper hand but just as he thinks he’s got what he wanted, he discovers perhaps there was something else he wanted more and it won’t wait for him any longer.

Based on a novel by hardboiled author Haruhiko Oyabu, Resurrection of Golden Wolf is another action vehicle for Matsuda at the height of his stardom. Re-teaming with Murakawa with whom he’d worked on some of his most famous roles including The Most Dangerous Game series, Matsuda begins to look beyond the tough guy in this socially conscious noir in which an angry young man rails against the system intent on penning him in. A mastermind genius, Asakura is leading a double life as a mild mannered accountancy clerk by day and violent punk by night, but he has every right to be angry. If his early speech to a colleague is to be believed, Asakura worked hard to get this job. A high school graduate with night school accreditation, he’s done well for himself, but despite his friend’s assurance that Asaukura is ahead in the promotion stakes he knows there’s a ceiling for someone with his background no matter how hard he works or how bright he is.

Under the terrible wig and unfashionable glasses he adopts for his work persona, Asakura has a mass of unruly, rebellious hair and a steely gaze hellbent on revenge against the hierarchical class system. He is not a good guy. Asakura’s tactics range from fisticuffs with street punks to molesting bar hostesses, date rape, and getting his (almost) girlfriend hooked on drugs as a means of control, not to mention the original cold blooded murder of the courier he stole the company’s money from in the first place. The fact he emerges as “hero” at all is only down to his refusal to accept the status quo and by his constant ability to stay one step ahead of everyone else. When the system itself is this corrupt, Asakura’s punkish rebellion begins to look attractive despite the unpleasantness of his actions.

Adding in surreal sequences where Asakura dances around his lair-like apartment in a quasi-religious ritual with his silver mask, plus bizarre editing choices, eerie music and incongruous flamenco, Murakawa’s neo-noir world is an increasingly odd one, even if not quite on the level of his next film, The Beast Must Die. Very much of its time and remaining within the upscale exploitation world, Resurrection of Golden Wolf is necessarily misogynistic as its female cast become merely pawns exchanged between men to express their own status. The tone remains hopelessly nihilistic as Asakura nears his goal of the appearance of a stereotypically successful life with an executive job and possible marriage to the boss’ daughter only to find his conviction wavering. Hopelessly bleak, dark, and sleazy, Resurrection of Golden Wolf is, nevertheless, a supreme exercise in style marrying Matsuda’s iconic image with innovative direction which is hard to beat even whilst swimming in some very murky waters.

Again, many variations on the English title but I’ve gone with Resurrection of Golden Wolf as that’s the one that appears on Kadokawa’s release of the 4K remaster blu-ray (Japanese subs only).

Original trailer (English subtitles)

Every story is a ghost story in a sense. In every photograph there’s a presence which cannot be seen but is always felt. The filmmaker is a phantom and an enigma, but can we understand the spirit from what we see? Whose viewpoint are seeing, and can we ever separate that subjective vision from the one we create for ourselves within our own minds? The Man Who Left his Will on Film (東京戰争戦後秘話, Tokyo Senso Sengo Hiwa) is an oblique examination of identity but more specifically how that identity is repurposed through cinema as cinema is repurposed as a political weapon.

Every story is a ghost story in a sense. In every photograph there’s a presence which cannot be seen but is always felt. The filmmaker is a phantom and an enigma, but can we understand the spirit from what we see? Whose viewpoint are seeing, and can we ever separate that subjective vision from the one we create for ourselves within our own minds? The Man Who Left his Will on Film (東京戰争戦後秘話, Tokyo Senso Sengo Hiwa) is an oblique examination of identity but more specifically how that identity is repurposed through cinema as cinema is repurposed as a political weapon.

Loosely based on Jules Michelet’s La Sorcière (Satanism and Witchcraft) which reframed the idea of the witch as a revolutionary opposition to the oppression of the feudalistic system and the intense religiosity of the Catholic church, Belladonna of Sadness (哀しみのベラドンナ, Kanashimi no Belladonna) was, shall we say, under appreciated at the time of its original release even being credited with the eventual bankruptcy of its production studio. Begun as the third in the Animerama trilogy of adult orientated animations produced by legendary manga artist Osamu Tezuka’s Mushi Productions, Belladonna of Sadness is the only one of the three with which Tezuka was not directly involved owing to having left the company to return to manga. Consequently the animation sheds his characteristic character designs for something more akin to Art Nouveau elegance mixed with countercultural psychedelia and pink film compositions. Feminist rape revenge fairytale or an exploitative exploration of the “demonic” nature of female sexuality and empowerment, Belladonna of Sadness is not an easily forgettable experience.

Loosely based on Jules Michelet’s La Sorcière (Satanism and Witchcraft) which reframed the idea of the witch as a revolutionary opposition to the oppression of the feudalistic system and the intense religiosity of the Catholic church, Belladonna of Sadness (哀しみのベラドンナ, Kanashimi no Belladonna) was, shall we say, under appreciated at the time of its original release even being credited with the eventual bankruptcy of its production studio. Begun as the third in the Animerama trilogy of adult orientated animations produced by legendary manga artist Osamu Tezuka’s Mushi Productions, Belladonna of Sadness is the only one of the three with which Tezuka was not directly involved owing to having left the company to return to manga. Consequently the animation sheds his characteristic character designs for something more akin to Art Nouveau elegance mixed with countercultural psychedelia and pink film compositions. Feminist rape revenge fairytale or an exploitative exploration of the “demonic” nature of female sexuality and empowerment, Belladonna of Sadness is not an easily forgettable experience. The saga seemed complete with the end of

The saga seemed complete with the end of  At the end of

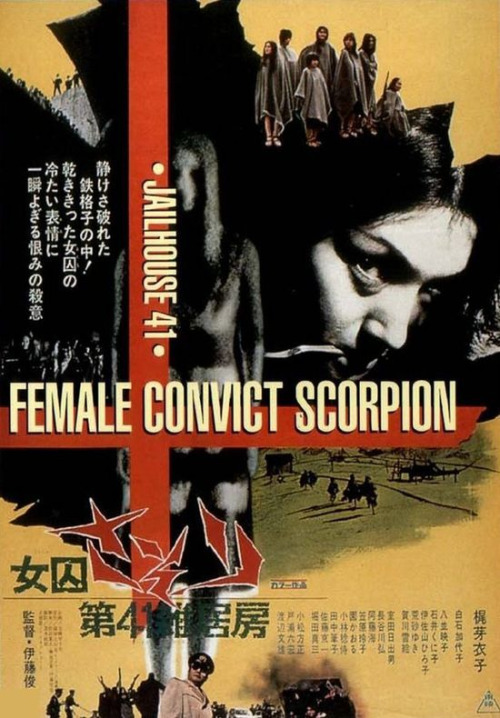

At the end of  Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41 (女囚さそり第41雑居房, Joshu Sasori – Dai 41 Zakkyobo) picks up around a year after the end of

Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41 (女囚さそり第41雑居房, Joshu Sasori – Dai 41 Zakkyobo) picks up around a year after the end of

Sparkling seas sound like hopeful things, especially if you’re a majestic seagull flying far above, bathed in perpetual sunshine. But then, perhaps the water below is shining with the shards of broken hopes which float on its surface, is its beauty treacherous or in earnest? So asks the singer of the title song which recurs throughout the film as if to undercut even its brief moments of happiness. There is precious little joy to be found in the lives of the two protagonists of Oh Seagull, Have You Seen the Sparkling Ocean? : An Encounter (鴎よ、きらめく海を見たか めぐり逢い, Kamome yo, Kirameku Umi wo Mitaka: Meguriai), only pain and confusion as they try to rebuild their ruined lives in an uncaring city.

Sparkling seas sound like hopeful things, especially if you’re a majestic seagull flying far above, bathed in perpetual sunshine. But then, perhaps the water below is shining with the shards of broken hopes which float on its surface, is its beauty treacherous or in earnest? So asks the singer of the title song which recurs throughout the film as if to undercut even its brief moments of happiness. There is precious little joy to be found in the lives of the two protagonists of Oh Seagull, Have You Seen the Sparkling Ocean? : An Encounter (鴎よ、きらめく海を見たか めぐり逢い, Kamome yo, Kirameku Umi wo Mitaka: Meguriai), only pain and confusion as they try to rebuild their ruined lives in an uncaring city. 1973 is the year the ninkyo eiga died. Or that is to say, staggered off into an alleyway clutching its stomach and vowing revenge whilst simultaneously seeking forgiveness from its beloved oyabun after being cruelly betrayed by the changing times! You might think it was Kinji Fukasaku who turned traitor and hammered the final nail into the coffin of Toei’s most popular genre, but Sadao Nakajima helped ram it home with the riotous explosion of proto-punk youth movie and jitsuroku-style naturalistic look at the pettiness and squalor inherent in the yakuza life – Aesthetics of a Bullet (鉄砲玉の美学, Teppodama no Bigaku). This tale of a small time loser playing the supercool big shot with no clue that he’s a sacrificial pawn in a much larger power struggle is one that has universal resonance despite the unpleasantness of its “hero”.

1973 is the year the ninkyo eiga died. Or that is to say, staggered off into an alleyway clutching its stomach and vowing revenge whilst simultaneously seeking forgiveness from its beloved oyabun after being cruelly betrayed by the changing times! You might think it was Kinji Fukasaku who turned traitor and hammered the final nail into the coffin of Toei’s most popular genre, but Sadao Nakajima helped ram it home with the riotous explosion of proto-punk youth movie and jitsuroku-style naturalistic look at the pettiness and squalor inherent in the yakuza life – Aesthetics of a Bullet (鉄砲玉の美学, Teppodama no Bigaku). This tale of a small time loser playing the supercool big shot with no clue that he’s a sacrificial pawn in a much larger power struggle is one that has universal resonance despite the unpleasantness of its “hero”. If the under seen yet massively influential director Yasuzo Masumura had one recurrent concern throughout his career, passion, and particularly female passion, is the axis around which much of his later work turns. Masumura might have begun with the refreshingly innocent love story

If the under seen yet massively influential director Yasuzo Masumura had one recurrent concern throughout his career, passion, and particularly female passion, is the axis around which much of his later work turns. Masumura might have begun with the refreshingly innocent love story