In the present day, South Korea has become a prosperous society and leading world economy, but the miracle of its modernisation came at a heavy price. Socially committed filmmaker Park Kwang-su’s A Single Spark (아름다운 청년 전태일, Areumdaun cheongnyeon Jeon Tae-il) takes a trip back to the “truly dark days” of the Park Chung-hee dictatorship to expose the exploitation on which the modern society was, and in fact still is, founded, enabled largely by the wilful misuse of a fear of “communism” as manifested in the problematic presence of threat from “the North”.

Park filters his true life tale through the figure of a fictionalised author and activist, Kim (Moon Sung-Keun), who finds himself on the run from the authorities in 1975. Hiding out in a small town in a backroom rented by his pregnant factory worker girlfriend Jung-soon (Kim Sunjae), Kim is working on a biography of a labour rights activist, Jeon Tae-il, who self-immolated in order to protest the failure to properly enforce existing workers’ rights five years’ earlier in 1970.

Switching to crisp black and white, Park paints a bleak picture of working class life in the late 1960s as the oppressive Park Chung-hee regime imposed extreme export goals designed to boost the local economy. We first meet Jeon (Hong Kyeong-in), who was only 22 at the time of his death, selling umbrellas on the street before he is “lucky” enough to get a job in a tailoring factory. Committing himself to working hard and getting on, he is quickly disillusioned with conditions at the plant which has little light or ventilation and often forces its employees to work through the night without adequate breaks for food. When the young woman next to him begins vomiting blood and is sent home but subsequently fired, Jeon becomes radicalised. Told that there are no laws which protect workers, he is surprised to discover that there are but their existence has been wilfully kept from him. The law is written in a language which is almost impossible for him to understand, in highly formal text using Chinese characters which most ordinary Koreans, never mind those like Jeon denied a proper education, struggle to read.

Jeon begins agitating. He takes a copy of the statutes and a series of violations at the factory to those in charge, but no one is interested. Even when he convinces some of the other workers to come with him, the boss is eventually forced to make a token concession of listening to them but ultimately rolls his eyes and says it’s all very well but not good for business. Jeon isn’t asking for anything radical (save the later addition of provision for menstrual leave), only for better ventilation and for the existing laws to be obeyed.

Meanwhile, Kim meditates on his legacy in the dark days of 1975 where anti-communist sentiment runs high in the wake of the end of the Vietnam War. “Anti-communism” and the demonisation of the North were a central part of Park Chung-hee’s right-wing, nationalist military dictatorship and any attempts to form things like unions or left-leaning political associations were quickly decried as “communist”. Kim’s girlfriend Jung-soon is currently involved in trying to set up a union at her factory to combat many of the same kinds of issues that Jeon was fighting five years’ earlier, but she too is under a lot of pressure. Afraid of the authorities and of losing their jobs, many workers refuse to join and even after she reaches her quota the request for recognition is denied. She and the other activists are harassed by factory management beginning with a “friendly” meeting outside her home in which they try to bribe her with money and expensive fruits, and ending with a raid on the building in which some of the workers are holding a protest during which a woman falls ill and the others are badly beaten when they try to get her to a hospital.

Jeon and the others are lectured by management that they should try to feel more “patriotic” and be willing to suffer in order to raise the economy, bribed with false promises that they’ll all be driving luxury cars in 10 years’ time. Meanwhile, a woman coming to collect money from Jeon’s mother angrily exclaims that debtors should take rat poison and die (which seems counterproductive when they owe you money), and the managers dismiss workers’ concerns with the rationale that they obviously “aren’t hungry enough” to put up with starvation wages and poor working conditions. From the vantage point of 1975, Kim meditates on Jeon’s sacrifice as he witnesses the suicide of another young man, Kim Sang-jin – a student who quoted Thomas Jefferson’s words that democracy is an outcome of struggle at a rally at Seoul National University before publicly slashing his belly. He sees the tragedy of Jeon’s death as the “single spark” which lit a fire under the democracy movement, a torch he wants to pick up and keep aflame to guide them towards a better future.

20 years later, Park may be acknowledging that some battles have been won in a newly democratised Korea as Kim looks on with satisfaction in a peaceful marketplace while a student carries the book he has written about Jeon Tae-il under his arm, but implicitly suggests that not enough has changed and the same battles Jeon was fighting are still being fought. A melancholy meditation on political martyrdom, art, and legacy, A Single Spark pays tribute to those who gave their lives for a fairer world but is equally intent that their sacrifice must not be forgotten.

A Single Spark was screened as part of the 2019 London Korean Film Festival.

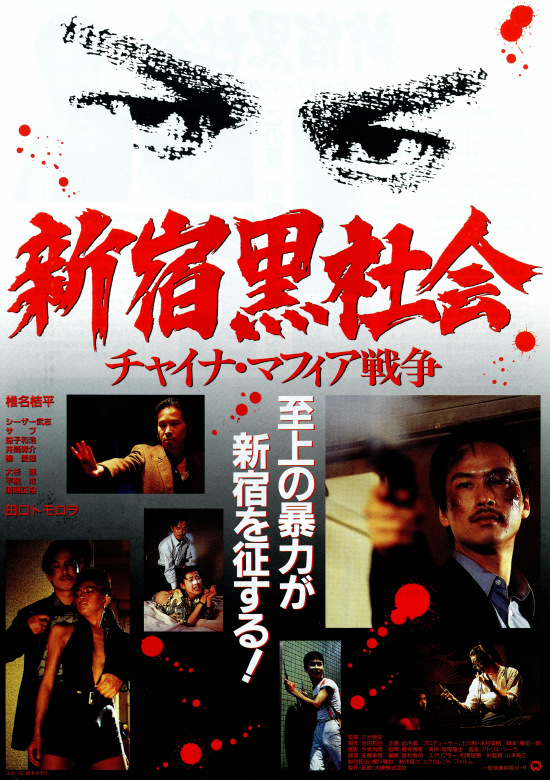

These days Takashi Miike is known as something of an enfant terrible whose rate of production is almost impossible to keep up with and regularly defies classification. Pressed to offer some kind of explanation to the uninitiated, most will point to the unsettling horror of

These days Takashi Miike is known as something of an enfant terrible whose rate of production is almost impossible to keep up with and regularly defies classification. Pressed to offer some kind of explanation to the uninitiated, most will point to the unsettling horror of  After completing his first “Onomichi Trilogy” in the 1980s, Obayashi returned a decade later for round two with another three films using his picturesque home town as a backdrop. Goodbye For Tomorrow (あした, Ashita) is the second of these, but unlike Chizuko’s Younger Sister or One Summer’s Day which both return to Obayashi’s concern with youth, Goodbye For Tomorrow casts its net a little wider as it explores the grief stricken inertia of a group of people from all ages and backgrounds left behind when a routine ferry journey turns into an unexpected tragedy.

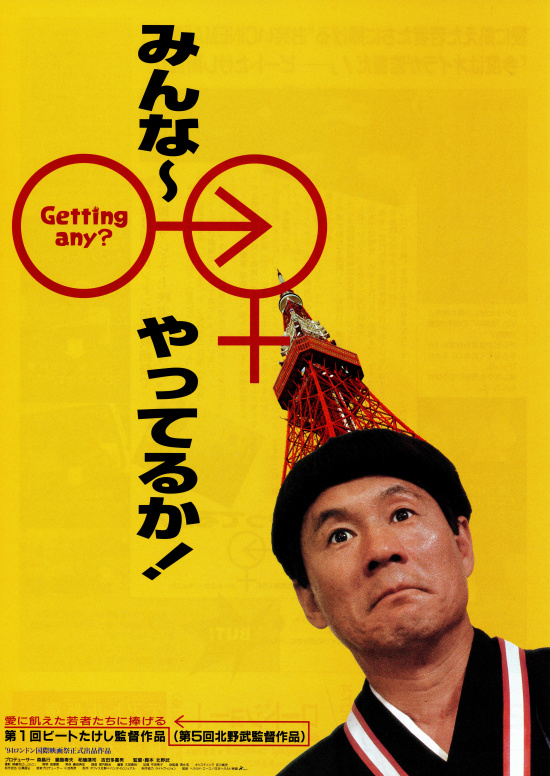

After completing his first “Onomichi Trilogy” in the 1980s, Obayashi returned a decade later for round two with another three films using his picturesque home town as a backdrop. Goodbye For Tomorrow (あした, Ashita) is the second of these, but unlike Chizuko’s Younger Sister or One Summer’s Day which both return to Obayashi’s concern with youth, Goodbye For Tomorrow casts its net a little wider as it explores the grief stricken inertia of a group of people from all ages and backgrounds left behind when a routine ferry journey turns into an unexpected tragedy. The recently prolific Sion Sono actually has a more sporadic film career dating back to the early 1980s though most would judge his real breakthrough to 2001’s Suicide Club. Back in the ‘90s Sono was most active as the leader of anarchic performance art troupe Tokyo Gagaga. Taking inspiration from the avant-garde theatre scene of the 1960s, Tokyo Gagaga took to the streets for flag waving protests and impressive, guerrilla stunts. Bad Film is the result of one of their projects – shot intermittently over a year using the then newly accessible Hi8 video rather the traditionally underground 8 or 16mm, Bad Film is near future set street story centring on gang warfare between the Chinese community and xenophobic Japanese petty gangsters with a side line in shifiting sexual politics.

The recently prolific Sion Sono actually has a more sporadic film career dating back to the early 1980s though most would judge his real breakthrough to 2001’s Suicide Club. Back in the ‘90s Sono was most active as the leader of anarchic performance art troupe Tokyo Gagaga. Taking inspiration from the avant-garde theatre scene of the 1960s, Tokyo Gagaga took to the streets for flag waving protests and impressive, guerrilla stunts. Bad Film is the result of one of their projects – shot intermittently over a year using the then newly accessible Hi8 video rather the traditionally underground 8 or 16mm, Bad Film is near future set street story centring on gang warfare between the Chinese community and xenophobic Japanese petty gangsters with a side line in shifiting sexual politics. Adolescent romance is complicated enough at the best of times but the barriers are ever higher if you happen to be gay in a less than tolerant society. Ryosuke Hashiguchi’s second feature Like Grains of Sand (渚のシンドバッド, Nagisa no Sinbad) takes a slight step back in time from

Adolescent romance is complicated enough at the best of times but the barriers are ever higher if you happen to be gay in a less than tolerant society. Ryosuke Hashiguchi’s second feature Like Grains of Sand (渚のシンドバッド, Nagisa no Sinbad) takes a slight step back in time from  Every once in a while an artist emerges whose work is so far ahead of its time that the audience of the day is unwilling to accept but generations to come will finally recognise for the achievement it represents. So it is for Sharaku – a young man whose abilities and ambitions are ruthlessly manipulated by those around him for their own gain. Brought to the screen by veteran new wave director Masahiro Shinoda, Sharaku (写楽) is an attempt to throw some light on the life of this mysterious historical figure who comes to symbolise, in many ways, the turbulence of his era.

Every once in a while an artist emerges whose work is so far ahead of its time that the audience of the day is unwilling to accept but generations to come will finally recognise for the achievement it represents. So it is for Sharaku – a young man whose abilities and ambitions are ruthlessly manipulated by those around him for their own gain. Brought to the screen by veteran new wave director Masahiro Shinoda, Sharaku (写楽) is an attempt to throw some light on the life of this mysterious historical figure who comes to symbolise, in many ways, the turbulence of his era. East has been meeting West in the movies from time immemorial and though it’s often assumed that the traffic is only running in one direction, in reality the river runs both ways. Kihachi Okamoto was always fairly open about his love of Hollywood westerns, particularly those of John Ford, and even mixed a fair amount of wild west style action to his 1959 Manchurian war movie, Desperado Outpost. Returning to the theme almost 40 years later in East Meets West (イースト・ミーツ・ウエスト), Okamoto retains his wry, ironic eye but adopts a tone much more in keeping with the slightly silly exploitation cowboy movies of the ‘70s.

East has been meeting West in the movies from time immemorial and though it’s often assumed that the traffic is only running in one direction, in reality the river runs both ways. Kihachi Okamoto was always fairly open about his love of Hollywood westerns, particularly those of John Ford, and even mixed a fair amount of wild west style action to his 1959 Manchurian war movie, Desperado Outpost. Returning to the theme almost 40 years later in East Meets West (イースト・ミーツ・ウエスト), Okamoto retains his wry, ironic eye but adopts a tone much more in keeping with the slightly silly exploitation cowboy movies of the ‘70s.