The thing that parents are supposed to do for their children is create a world that’s safe where they will always be loved, accepted, and taken care of while also teaching them how to survive in a sometimes hostile environment. Sometimes, however, that safe space is punctured and a child becomes separated from their guardian. Kim So Yong’s Treeless Mountain (나무없는 산, Namueobsneun San) is the story of one little girl’s painful journey towards an early acceptance of rootless independence as she and her sister try to come to terms with the abrupt exit of their mother and the loss of the world they’d known.

The thing that parents are supposed to do for their children is create a world that’s safe where they will always be loved, accepted, and taken care of while also teaching them how to survive in a sometimes hostile environment. Sometimes, however, that safe space is punctured and a child becomes separated from their guardian. Kim So Yong’s Treeless Mountain (나무없는 산, Namueobsneun San) is the story of one little girl’s painful journey towards an early acceptance of rootless independence as she and her sister try to come to terms with the abrupt exit of their mother and the loss of the world they’d known.

Jin (Kim Hee-yeon) and her younger sister Bin (Kim Song-hee) live in a cramped Seoul apartment in a run down part of town. Their father having abandoned the family, the girls’ mother (Lee Soo-ah) works during the day while a neighbour looks after Bin until Jin gets out of school and the girls look after each other until mum comes home. Though the girls’ mother is kind and patient, she is also exhausted and has little time for anything other than a hasty dinner and trying to get the sisters to bed in good time. However, the morning after an awkward conversation with the landlady that her mother didn’t want to talk about, Jin gets back from school to find removal men already dismantling her home and is bundled onto a bus out of the city. She and her sister will be staying with Big Aunt (Kim Mi-hyang) in the country while her mother takes off to look for their long absent dad in the hope that she can convince him to reassume his responsibilities.

Jin’s mother does not have a particularly good support network or other people to rely on and has been forced to leave her daughters with Big Aunt, her absent husband’s older sister, whom she barely knows. If she did know her, she’d know Big Aunt is not a good person to leave children with. Though not actively abusive, Big Aunt is a severe, embittered older woman who does nothing but complain and make it clear to the sisters just how inconvenient she feels their existence to be. Big Aunt used to have her own business but it’s gone bust and now she spends her days soaked in soju and regret. She makes Jin and Bin do odd jobs around the house (one of which is clearing away the worrying number of empty soju bottles in the property) and berates them each time something is not to her liking. Jin, an anxious child, often wets the bed. When it happened at home her mother patiently cleaned her up and told her not to worry, but Big Aunt is furious and Jin lets Bin take the blame rather face her wrath directly.

When she left, Jin’s mother gave her a plastic red piggy bank and told the girls that their aunt would give them a coin everyday and that when the piggy was full she’d return. Facing their aunt’s ongoing neglect, the girls convince themselves that the piggy bank is magic and that if they can fill it up on their own their mother will come back. They start their own business selling grilled grasshoppers that a local boy showed them how catch and cook, and then hatch on the revelatory idea that they can turn their big coins into lots of smaller coins to fill the bank up faster but, of course, their mother still doesn’t appear and it’s merely another illusion shattered in their rapidly maturing minds. The girls find temporary relief at the home of another local woman whose son has Down’s Syndrome and is also lonely because the other kids don’t seem to play with him, but mostly they’re on their own, waiting for their mother to come back so everything will go back to normal but becoming increasingly worried that it never will.

Eventually, Big Aunt shuffles them onto their elderly grandparents who were not exactly keen to take them in either, but once they’re there it’s not so bad. Grandma is a nice woman who shows them much more affection than Big Aunt and invites rather than forces them to help her with various tasks around the farm. City kids, the children are fascinated by the natural world and begin to enjoy spending time with grandma who shares with them her knowledge while the girls begin to understand that grandma is suffering too by catching sight of her ruined shoes echoing the painful too-smallness of Jin’s own as her heels poke out from the back of her trainers. Jin, who was often lonely and resentful, constantly told she had to look after her sister all while no one was looking after her, begins to cede ground to others in accepting that perhaps her mother won’t come back but maintaining the fantasy for Bin even as she begins to find a place for herself on grandma’s farm independent of adult care or control.

Treeless Mountain screens at the Pheonix on 3rd November, 1pm as part of the 2018 London Korean Film Festival.

International trailer (English Subtitles)

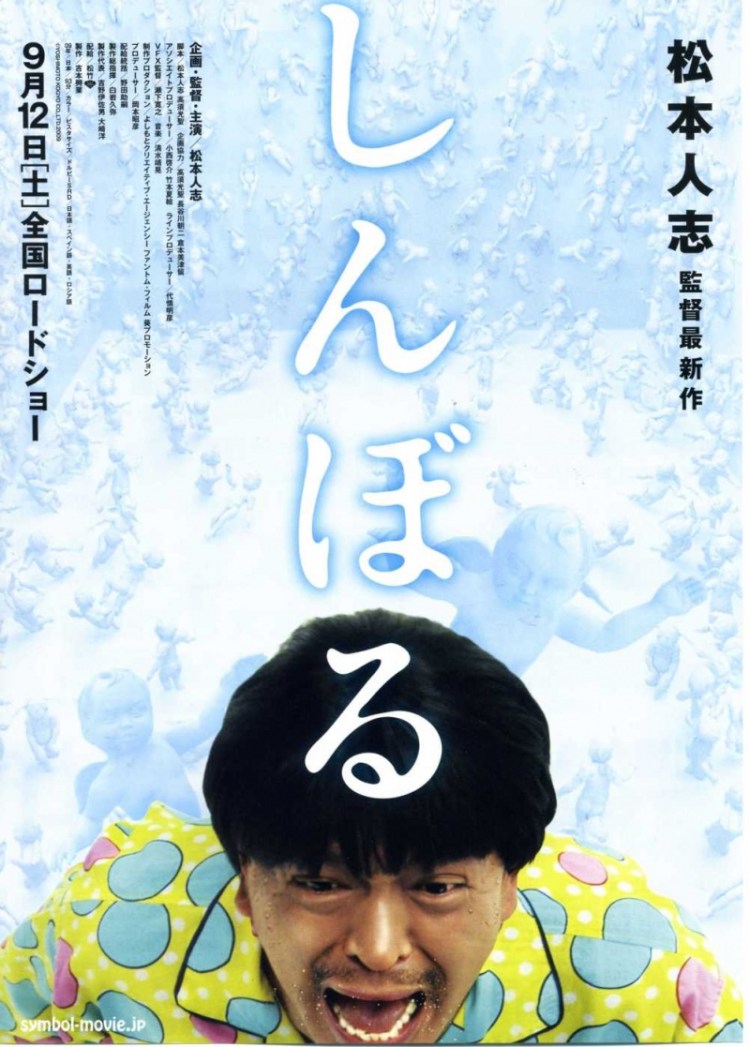

Symbol (しんぼる) – one thing which stands for another, sacrificing its own nature in service of something else. Hitoshi Matsumoto waxes philosophical in his follow up to Big Man Japan. Life, the universe, and everything converge in the seemingly unrelated tales of an unsuccessful Mexican luchador, and a confused Japanese man trapped in a surrealist nightmare. As expected, these two strands eventually meet, though not quite as one might expect.

Symbol (しんぼる) – one thing which stands for another, sacrificing its own nature in service of something else. Hitoshi Matsumoto waxes philosophical in his follow up to Big Man Japan. Life, the universe, and everything converge in the seemingly unrelated tales of an unsuccessful Mexican luchador, and a confused Japanese man trapped in a surrealist nightmare. As expected, these two strands eventually meet, though not quite as one might expect. When you spent your youth screaming phrases like “no future” and “fumigate the human race”, how are you supposed to go about being 50-something? A&R girl Kanna is about to find out in Kankuro Kudo’s generation gap comedy The Shonen Merikensack (少年メリケンサック) as she accidentally finds herself needing to sign a gang of ageing never were rockers. A nostalgia trip in more ways than one, Kudo is on a journey to find the true spirit of punk in a still conservative world.

When you spent your youth screaming phrases like “no future” and “fumigate the human race”, how are you supposed to go about being 50-something? A&R girl Kanna is about to find out in Kankuro Kudo’s generation gap comedy The Shonen Merikensack (少年メリケンサック) as she accidentally finds herself needing to sign a gang of ageing never were rockers. A nostalgia trip in more ways than one, Kudo is on a journey to find the true spirit of punk in a still conservative world.

Paju (파주) is the name of a city in the far north of Korea, not far from “the” North, to be precise. Like the characters who inhabit it, Paju is a in a state of flux. Recently invaded by gangsters in the pay of developers, the old landscape is in ruins, awaiting the arrival of the future but fearing an uncertain dawn. Told across four time periods, Paju begins with Eun-mo’s (Seo Woo) return from a self imposed three year exile in India, trying to atone for something she does not understand. Much of this has to do with her brother-in-law, Joong-shik (Lee Sun-kyun), an local activist and school teacher with a troubled past. Love lands unwelcomely at the feet of two people each unable to make us of it in this melancholy coming of age tale shot through with tragic irony.

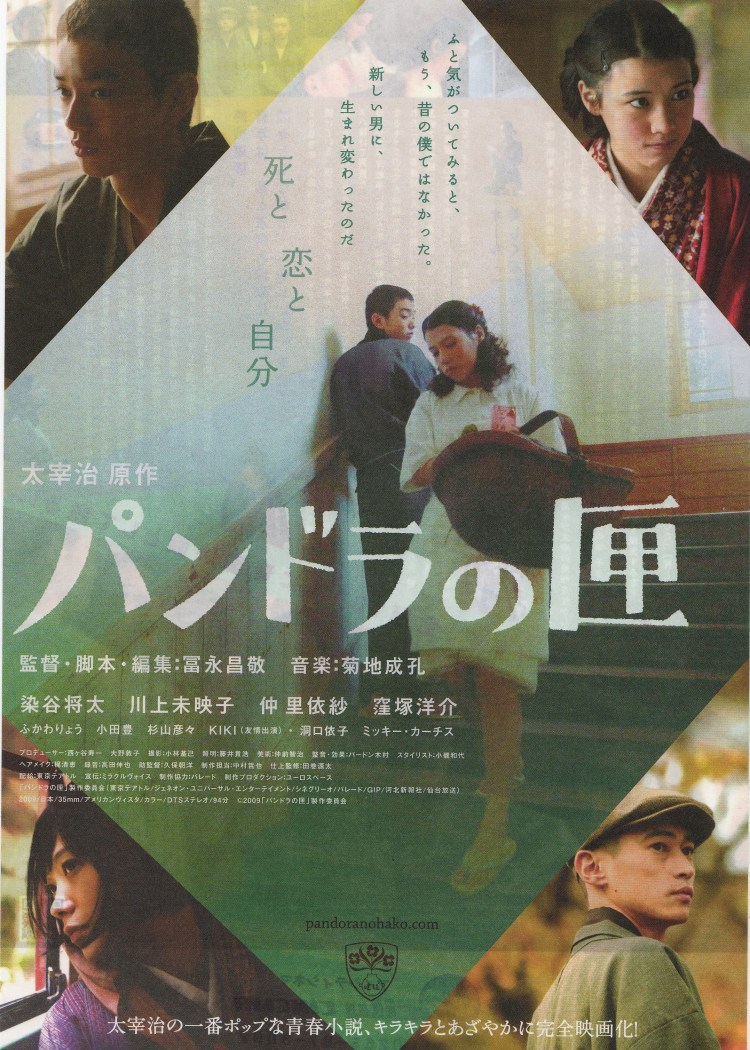

Paju (파주) is the name of a city in the far north of Korea, not far from “the” North, to be precise. Like the characters who inhabit it, Paju is a in a state of flux. Recently invaded by gangsters in the pay of developers, the old landscape is in ruins, awaiting the arrival of the future but fearing an uncertain dawn. Told across four time periods, Paju begins with Eun-mo’s (Seo Woo) return from a self imposed three year exile in India, trying to atone for something she does not understand. Much of this has to do with her brother-in-law, Joong-shik (Lee Sun-kyun), an local activist and school teacher with a troubled past. Love lands unwelcomely at the feet of two people each unable to make us of it in this melancholy coming of age tale shot through with tragic irony. Osamu Dazai is one of the twentieth century’s literary giants. Beginning his career as a student before the war, Dazai found himself at a loss after the suicide of his idol Ryunosuke Akutagawa and descended into a spiral of hedonistic depression that was to mark the rest of his life culminating in his eventual drowning alongside his mistress Tomie in a shallow river in 1948. 2009 marked the centenary of his birth and so there were the usual tributes including a series of films inspired by his works. In this respect, Pandora’s Box (パンドラの匣, Pandora no Hako) is a slightly odd choice as it ranks among his minor, lesser known pieces but it is certainly much more upbeat than the nihilistic Fallen Angel or the fatalistic

Osamu Dazai is one of the twentieth century’s literary giants. Beginning his career as a student before the war, Dazai found himself at a loss after the suicide of his idol Ryunosuke Akutagawa and descended into a spiral of hedonistic depression that was to mark the rest of his life culminating in his eventual drowning alongside his mistress Tomie in a shallow river in 1948. 2009 marked the centenary of his birth and so there were the usual tributes including a series of films inspired by his works. In this respect, Pandora’s Box (パンドラの匣, Pandora no Hako) is a slightly odd choice as it ranks among his minor, lesser known pieces but it is certainly much more upbeat than the nihilistic Fallen Angel or the fatalistic  Poor old Hyuk-jin is about to have the worst “holiday” of his life in Noh Young-seok’s ultra low budget debut, Daytime Drinking (낮술, Natsul). Currently heartbroken and lovesick as his girlfriend has just broken up with him, Hyuk-jin is trying to cheer himself up with an evening out drinking with old university friends. Truth be told, they aren’t terribly sympathetic to his pain though one of them suddenly suggests they all take a trip together just like they did when they were students. Hyuk-jin plays the party pooper by saying he can’t go because he’s meant to be looking after the family dog but after some gentle ribbing he relents and says he’ll come if he can get someone to look in on the puppy for him while he’s gone. He will regret this.

Poor old Hyuk-jin is about to have the worst “holiday” of his life in Noh Young-seok’s ultra low budget debut, Daytime Drinking (낮술, Natsul). Currently heartbroken and lovesick as his girlfriend has just broken up with him, Hyuk-jin is trying to cheer himself up with an evening out drinking with old university friends. Truth be told, they aren’t terribly sympathetic to his pain though one of them suddenly suggests they all take a trip together just like they did when they were students. Hyuk-jin plays the party pooper by saying he can’t go because he’s meant to be looking after the family dog but after some gentle ribbing he relents and says he’ll come if he can get someone to look in on the puppy for him while he’s gone. He will regret this.