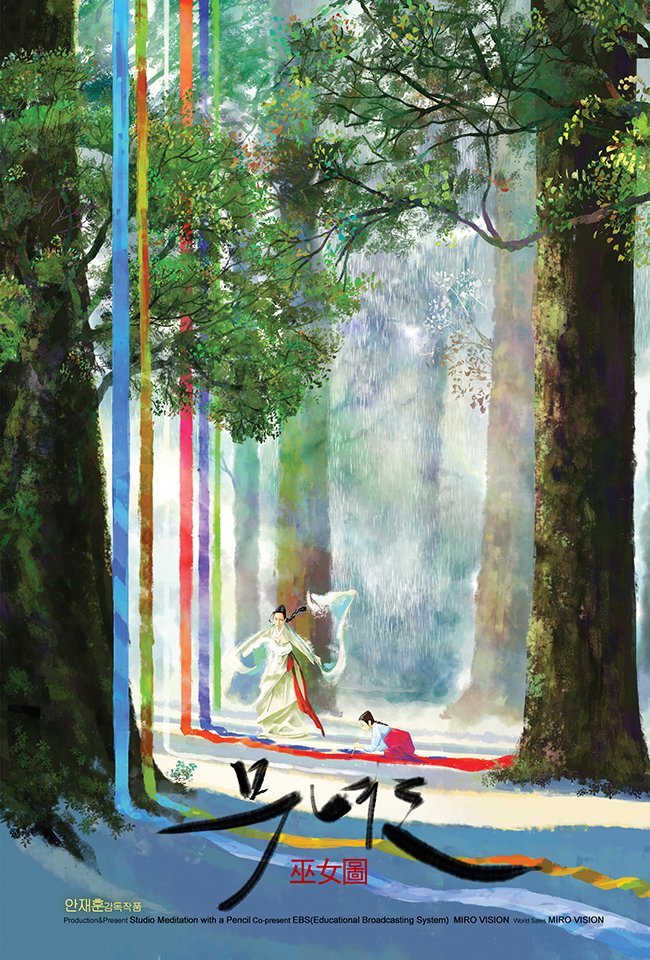

Inspired by a well known short story first published in 1936, Ahn Jae-hun’s painterly animation The Shaman Sorceress (무녀도, munyeodo) situates itself in a Korea at a moment of acute crisis, presented with images of “modernity” which are inevitably bound with those of Westernisation though the conflicts we are presented with are largely ideological and spiritual rather social or political. Nevertheless, there is an unavoidable lament for a lost Koreanness and infinite sadness for those undone by their own inability to find accommodation with changing times.

Like many similar tales from Korea, Shaman Sorceress opens with a framing sequence which is never closed in which the narrator reflects on what is technically the film’s present from some point in the future. He reveals that he is from a noble family and that his grandfather was once known as a connoisseur of art and antiques, but the world is changing and the age of the aristocracy is coming to a close. Faced with declining fortunes, the family has sold off most of its collection and so they rarely receive so many visitors as they once did but are keen to receive those they do which is why his grandfather gives temporary lodging to a prodigious young painter, Nang-Yi, the 17-year-old orphaned daughter of a shamaness who lost her hearing in childhood illness.

The narrator then goes on to relate Nang-Yi’s story which was related to him by his grandfather who heard it from the man with whom Nang-Yi was travelling. This is not actually about Nang-Yi, who becomes something like the protector of traditional Korean culture through her survival and her art, but her mother, an usual woman of the Joseon era who found herself surviving alone on the margins of society. Mohwa (So Nya) never marries but has two children by different men and resolves to raise both of them alone. Aware that her bright son Wook-Yi (Kim Da-hyun) lacks male influence, she decides to send him to the temple at 9 years old to further his education and increase his future prospects. His younger sister Nang-Yi, however, falls into such a depression in his absence that she becomes ill and loses her hearing further adding to Mohwa’s sense of maternal guilt. When she too falls ill and begins having visions, Mohwa awakens as a shamaness ministering to the townspeople who account her a powerful interceder with the supernatural able to cure the most serious of ills.

The crisis occurs when 15-year-old Wook-Yi leaves the temple for the city where he is “corrupted” by modernity in the form of Western Christianity as preached by American missionaries. Disillusioned with Buddhism, he is converted by the idea of a single loving God and hopes to save the souls of those around him but is insensitive to his mother’s beliefs as a shamaness while she in turn is intolerant of his new faith, believing he has been possessed by “that Jesus ghost”. What transpires between them as perhaps any parent and child is a tussle over the future, but their tragedy is that their ideology is so mutually exclusive that they can find no way to co-exist while Nang-Yi is trapped between them as a representative of the chaotic present neither allied with past or future.

The film, however, leans heavily towards a defence of Christianity even as it criticises both mother and son for their rigid dogmatism, neither able to accept that their way is not the only way. Mohwa faces existential threat as a shamaness who is no longer feared or respected, her noisy rituals seen as backward while the townspeople increasingly flock towards the subdued power of prayer while edging towards a moral austerity which condemns her for living outside of socially conservative patriarchal social codes as an unmarried mother of two allowed greater freedom in her spiritual authority. “Life’s supposed to be lonely” she explains to a departed soul she’s trying to convince to move on, but might as well be talking to herself as she tries to accommodate her grief and maternal guilt but finds herself prevented from moving on into a new modernity of which Christianity is only a part.

The overriding sentiment is one of futility in an acceptance that progress will always win in the end, as reflected in the narrator’s wistful lament of his noble family’s gradual decline. Seemingly aimed at a wide audience not exclusively adult, Ahn tackles some difficult themes from alcoholism to incestuous desire not to mention the more complex meditation on the loss of the feudal past and the costs of modernity while continuing to express the conflict musically in his use of traditional singing styles in Mohwa’s rituals and a more conventional broadway register in Wook-Yi’s passionate defences of his faith. While the frequent flights into song may seem incongruous, they are perhaps more common in Korean animation of this kind than they might be in that from other cultures, particularly in films not expressly aimed at younger children who are unlikely to engage with the weighty themes despite the simplistic yet often beautiful aesthetics which present a less complicated view of the feudal past as one of idyllic pastoralism.

Festival trailer (dialogue free)