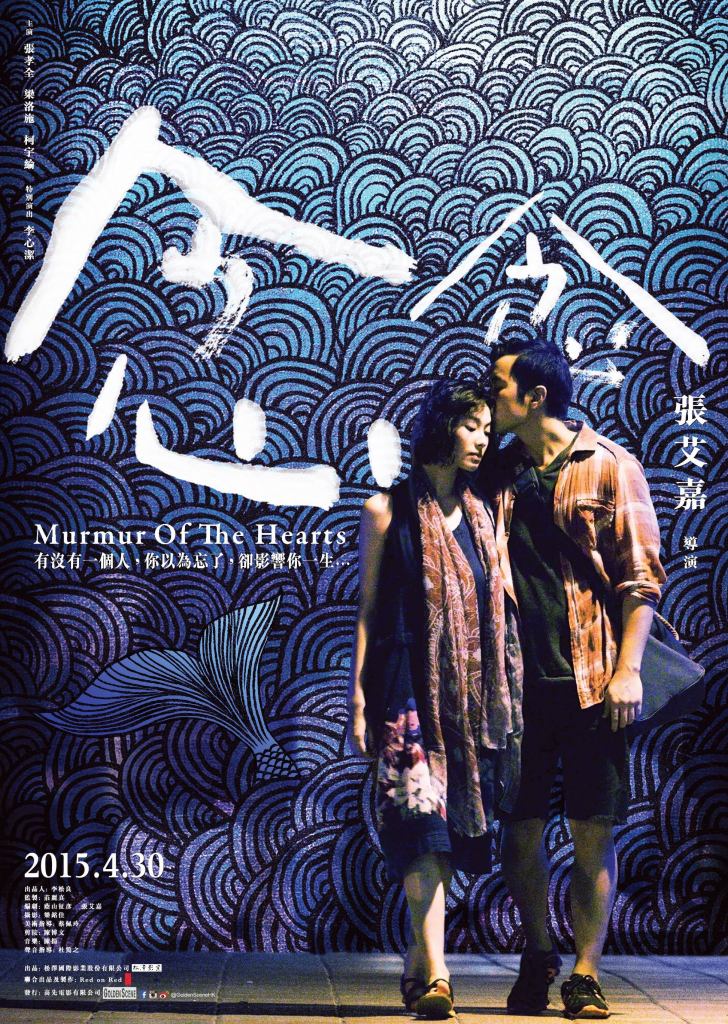

A legacy of abandonment frustrates the futures of three orphaned adults in Sylvia Chang’s moving drama, Murmur of the Hearts (念念, Niàn Niàn). Marooned in their own small pools, they yearn for the freedom of oceans but find themselves unable to let go of past hurt to move into a more settled adulthood, eventually discovering that there is no peace without understanding or forgiveness and no path to freedom without learning to let go of the shore.

The heroine, Mei (Isabella Leong), is an artist living in Taipei and apparently still consumed with rage and resentment towards her late mother. She is in a troubled relationship with a down on his luck boxer, Hsiang (Joseph Chang Hsiao-chuan), who has abandonment issues of his own that are compounded by toxic masculinity which leaves him feeling inadequate in failing to live up to the expectations of his long absent father. Mei’s long lost brother, Nan (Lawrence Ko), meanwhile is now a melancholy bachelor in his 30s who, unlike all the other young men, never swam far from home, working for a tourist information company on Green Island which, though once notorious as a penal colony housing political prisoners during the White Terror has now become a tourist hotspot thanks to its picturesque scenery.

Like one whole cleaved in two youthful separation weighs heavily on each of the siblings who cannot but help feel the absence of the other. Their mother, Jen (Angelica Lee Sinje), trapped in the oppressive island society, was fond of telling them stories about a mermaid who escaped her palace home by swimming towards the light and the freedom of the ocean. She tells the children to be the “angels” rescuing the little fish trapped in rock pools by sending them “home” to the sea, and, it seems, eventually escaped herself taking Mei with her but leaving Nan behind. Neither sibling has been ever been able to fully forgive her, not Mei who lost both her family and her home in the city, or Nan who stayed behind with his authoritarian father wondering if his mother didn’t take him him because she loved his sister more.

Mei, meanwhile feels rejected by her father after overhearing him on the phone saying he wanted nothing to do with either of them ever again. Idyllic as it is, the island wears its penal history heavily as a permanent symbol of the authoritarian past which is perhaps both why Mei has never returned, and why Nan has remained afraid to leave. Unable to make peace with the past they cannot move forward. Mei’s life has reached a crisis point in the advent of maternity. She is pregnant with Hsiang’s child but conflicted about motherhood in her unresolved resentment towards her mother while insecure in her relationship with the emotionally stunted Hsiang who, likewise, is terrified of the idea of fatherhood because of his filial insecurity.

Only by facing the past can they begin to let it go. Chang shifts into the register of magical realism as a mysterious barman arrives to offer advice to each of the siblings, Nan indulging in an uncharacteristic drinking session while sheltering from a typhoon on the evening his father that his father dies and somehow slipping inside a memory to converse with the mother who was forced to leave him behind, coming to see the love in her abandonment. Jen told him that she wanted him to see the world, but he is reluctant even to go Taipei and afraid to seek out his sister.

Jen’s battle was, it seems, to save her children from the oppressions of Green Island, to be their angel returning them to the great ocean she herself felt she’d been denied. She wanted her children to be “creative”, resisting her abusive, authoritarian husband and his fiercely conservative, patriarchal ideals but eventually left with no option other than to leave. Yet the children flounder, left without guidance or harbour. “I don’t know where my home is”, Mei laments, revealing that she only feels real and alive when angry. For all that, however, it’s Jen’s story that finally sets them free, showing them path away from the prison of the past and finally returning them to each other united by a shared sense of loss but unburdened by fear or resentment in a newfound serenity.

Murmur of the Hearts streams online for free in the US as part of Asian Pop-Up Cinema’s Mini-Focus: Taiwan Cinema Online on June 9.

Original trailer (English subtitles)