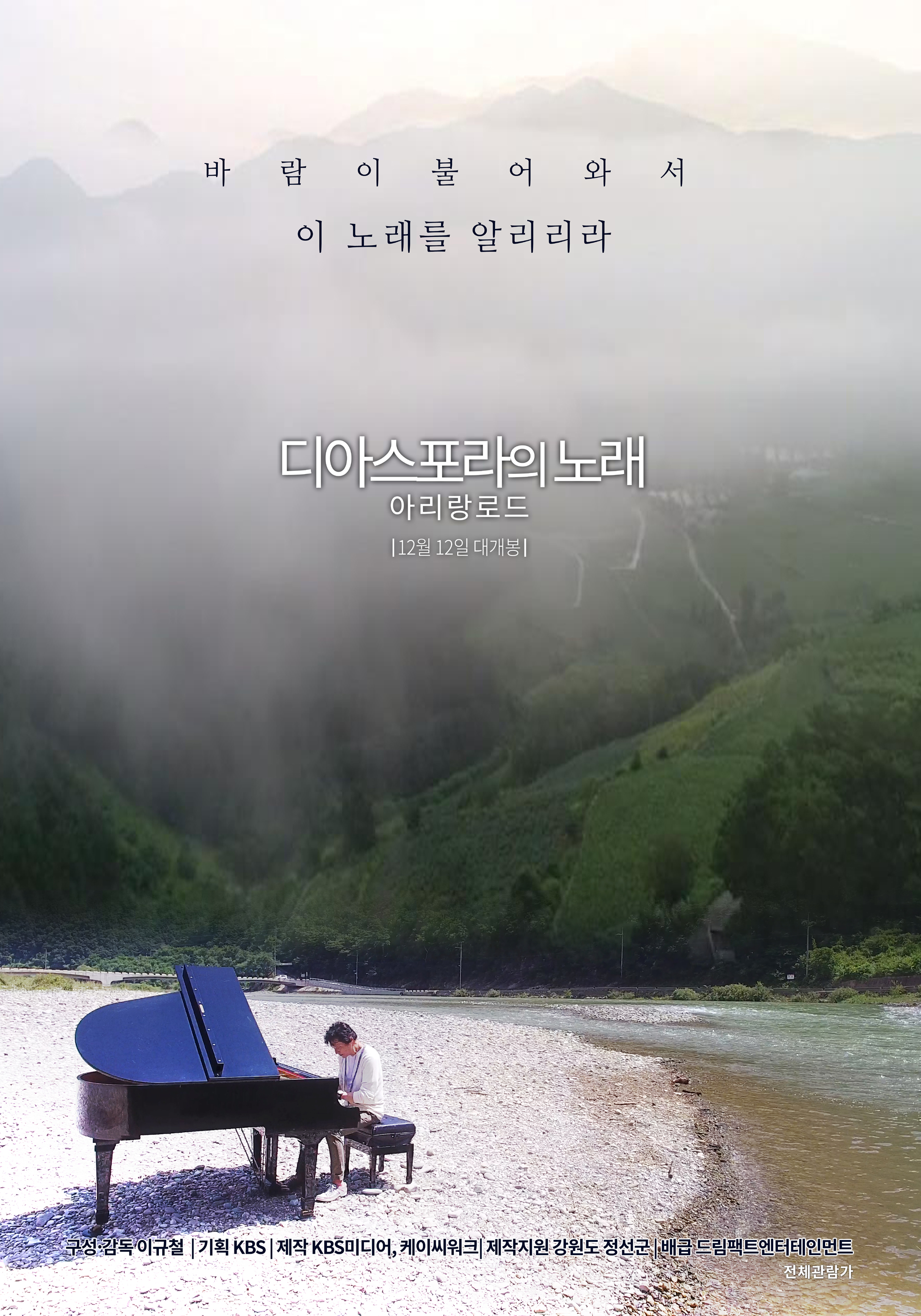

A song from home can be a powerful thing when you’re far away, as the various protagonists of Lee Kyu-chul’s Diaspora: Arirang Road (디아스포라의 노래: 아리랑 로드, Diaspora-eui Nolae: Arirang Road) make plain. Though they perhaps can no longer remember all the words, or are too overcome by emotion to be able to sing, each of Lee’s overseas Koreans has a deep connection to the melancholy folk song which sings, as one farmer puts it, of “the grief of living” but as others affirm is also full of life and hope if only in the solidarity of voices raised together in shared hardship.

The guide, Korean-Japanese composer Yang Bang-ean, is on a quest to write his own version of Arirang, a new version which sings in the voices of the diaspora. Yang was himself born in Japan to Korean parents and is a member of the zainichi community committed to cross-cultural exchange. Unsurprisingly the first half of the film is dedicated to the Koreans who found themselves in Japan sometimes against their will, trafficked as forced labour during the colonial era and taking solace in Arirang while enduring harsh treatment and discrimination at the hands of the Japanese. In a brief reconstruction, a miner reads a letter to his mother in which he hides how much he is suffering, later likening himself to an octopus tricked into a pot, gradually consuming itself in a desperate attempt to survive.

Unlike many folksongs, little of Arirang is fixed aside from the distinctive chorus leaving melody and lyrics open to interpretation meaning there are thousands of different versions found all over Korea and beyond. The action later shifts to a perhaps forgotten diaspora community, the Koreans of Central Asia who travelled to Russia in search of a better life only to be moved on by Stalin in the 1930s as international tensions escalated. Packed onto a fetid train travelling for days on end with many dying during the journey from cold, stress, or hunger, they had only Arirang to unite them and offer hope that their lives would one day be better.

As as someone puts it, Arirang is the “tragic history of a scattered people”, but also “a belief of our history and future”. According to another singer, it is “love. life. and living”, running like water with the rhythms of nature and leading those who share the song toward hope. Yang later re-characterises the song as both personal and universal, the singer in a sense becoming Arirang and Arirang the singer in a process of mutual change and evolution, something which is perhaps underway as he continues to write his own Arirang for those Koreans who remain outside of Korea.

As many of the singers point out, there is much grief and sorrow in Arirang but also hope and a spirit of endurance. Lee Kyu-chul shows us two different burial grounds on different sides of the Earth, the first marked only with stones for Koreans buried anonymously in Japan, and the second a small city of walled headstones for those who died peacefully of old age in Kazakstan. Those who survived the train later prospered and endured, their grandchildren born and raised in Kazakstan but still united by Arirang as a marker of their culture while one young man enthusiastically belts out a K-pop tune to remind us they’ve not forgotten their roots.

Yang concludes his performance with an intense jam session of various artists each forging a new Arirang together, testimony to the power the song has to bring people together as it has with Yang and the members of the Korean diaspora he has met from all over the world in some ways very like him and in other ways not but united in their Koreanness through the memory and the sentiment of Arirang no matter what lyrics they sang or what hardship they endured. A heartfelt tribute to the solidarity of voices raised in song and the cathartic properties of music, Lee Kyu-chul’s folksong odyssey rediscovers the invisible connections of the diasporic community brought together by the power of Arirang which offers, as Yang puts it, “the opportunity to hope” even in the depths of despair.

Diaspora: Arirang Road streams in the US Sept. 10 to 14 as part of the 11th season of Asian Pop-Up Cinema.

Original trailer (English subtitles)