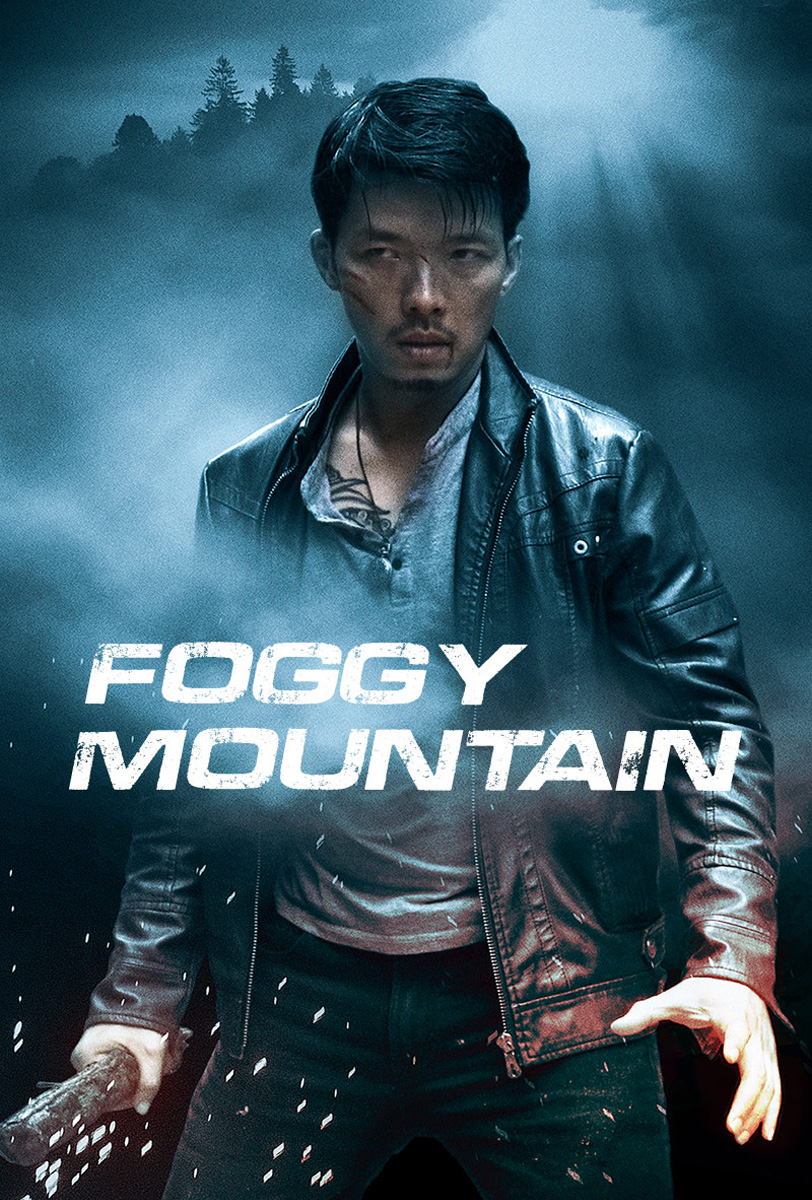

“You’ve blown things way out of proportion,” according to a man who still doesn’t think he’s done anything to deserve dying for. But as his boss told him, though they may exploit women, sell drugs, and kill people, they have rules. Lee Chung-hyun’s pulpy action thriller Ballerina (발레리나) sees a former bodyguard go after the gangster who drugged and raped her friend with the consequence that she later took her own life.

In recent years there have been a series of real life scandals involving women being drugged in nightclubs and sexually assaulted with videos either uploaded to the internet or used as leverage for blackmail often to force women to participate in sex work. Ballerina Min-hee (Park Yu-rim), seemingly the only friend of bodyguard Ok-ju (Jeon Jong-seo), was raped by drug dealer Choi (Kim Ji-hoon) and thereafter quite literally robbed of the ability to dance. Preoccupied with her trauma, she missteps and injures herself ruining her dance career and leaving her with nothing. There is something quite poignant in the fact Choi sells the drugs in the small, fish-shaped bottles that usually house soy sauce in pre-packed sushi given that Min-hee later says that she wants to come back as a fish in her next life and live in the ultimate freedom of the sea. Dance to her seemed to be a means of finding a similar kind of free-floating freedom, but the trauma of Choi’s assault has taken that from her.

Meanwhile, the loss of Min-hee has robbed Ok-ju of something similar. On first re-connecting with her former high school friend, Ok-ju says she worked as some kind of corporate bodyguard but the organisation is clearly larger than that and involved with some additionally shady stuff that suggests her job may actually have involved some sort of spy and assassin work. In any case, it had left her feeling empty as if she were slowly dying inside. Only on meeting Min-hee does she finally start to feel alive again and has apparently left the organisation she was working for in order to live a more fulfilling life though she may not actually have achieved that just yet. There is nothing really to suggest there is anything more between the two women than friendship, though the intensity of Ok-ju’s feelings suggests there might have been.

Even so, there’s more to Ok-ju’s mission than simple revenge as she finds herself taking down the entire organisation in order to make her way towards Choi. She’s aided by another young woman dressed as a high school student (Shin Se-hwi) who looks to her for salvation, explaining that she has a plan, she’s just been waiting for someone like Ok-ju to show up and help her while the former handler Ok-ju turns to in search of support is also a woman making her mission one of female solidarity against ingrained societal misogyny. “You thought we were easy prey,” Ok-ju challenges Choi making it clear that he made a huge mistake though he continues to taunt her about Min-hee and deflect his responsibility insisting that he hasn’t done anything to warrant this kind of treatment because the abuse and trafficking of women is not something he regards as a big deal.

Ok-ju and the girl obviously feel differently. There’s something very satisfying about the way Ok-ju methodically cuts through a host of bad guys without granting them any kind of authority over her. The action sequences are often urgent and frenetic while showcasing Ok-ju’s skills and the lack of them in the male henchmen, but there’s also a fair bit of humour such as her using tins of pineapple to block knife attacks in the convenience store opener. The film indeed has its share of quirkiness such as the geriatric couple who arrive to supply Ok-ju with weapons but mainly have buckets full of revolvers that look like something out of the wild west before grabbing a flamethrower from the back, while the aesthetic also has a stylish retro feel with its purple and yellow colour palette. Pulpy in the extreme, the film’s stripped-back quality provides little background information and keeps dialogue to a minimum but more than makes up for it in its visual language and often beautiful cinematography.

Trailer (English subtitles)