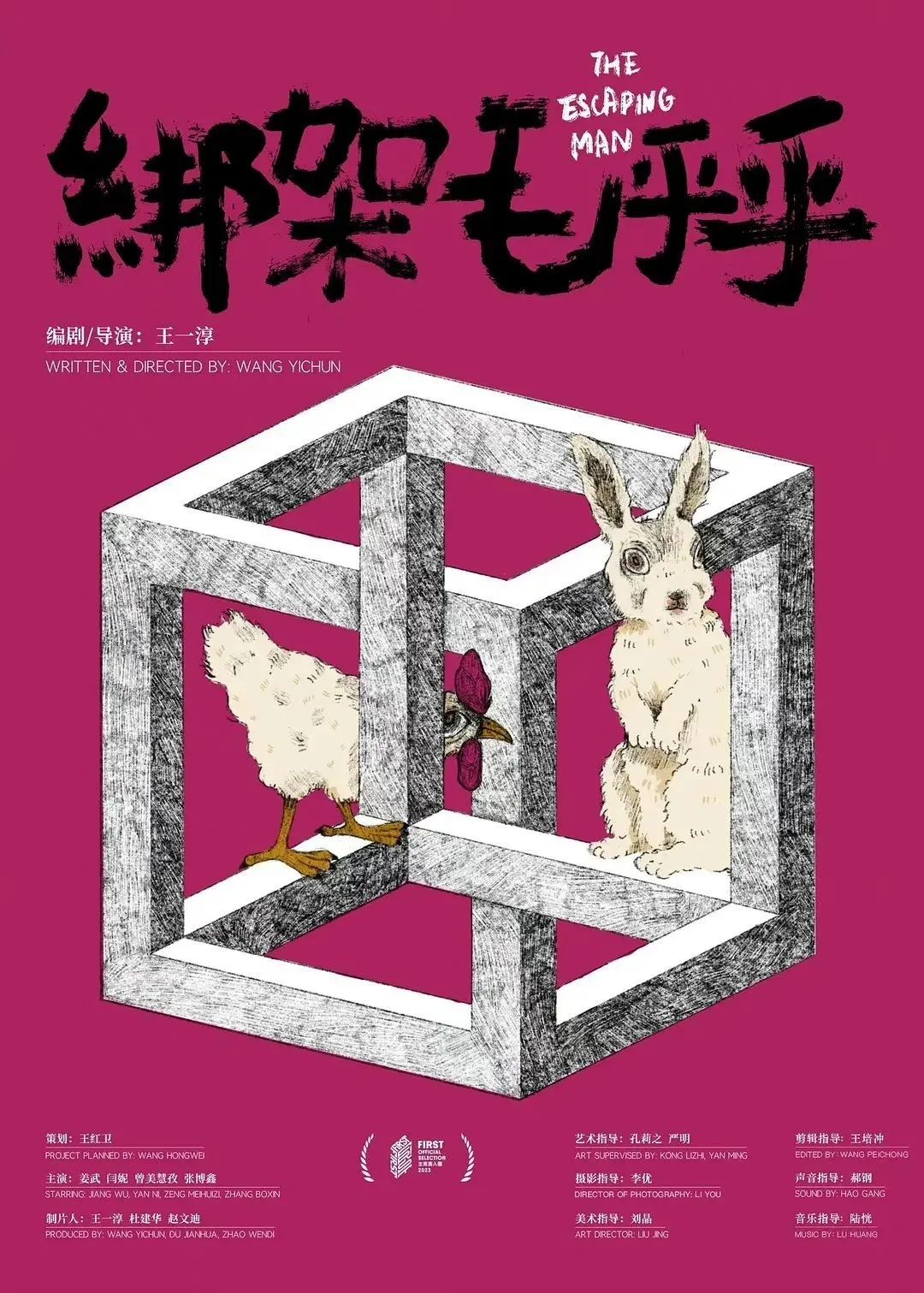

“Life isn’t much better on the outside,” according to Sia (Zeng Meihuizi), the heroine of Wang Yichun’s deliciously ironic dramedy, The Escaping Man (绑架毛乎乎). Escaping men is in part what she’s tried but otherwise failed to do while constrained by the socio-economic conditions and entrenched patriarchy of the modern China. All of the men in the film are, as many call them, “idiots”, but all things considered it might not necessarily be such a bad thing to be even if their guilelessness makes them vulnerable to the world around them albeit in much different ways to Sia.

At least its this boundless cheerfulness and inability to see the world’s darkness that caused Fluffy (Eric Zhang) to be rejected by his status-obsessed mother (Yan Ni) who seems to have got rich by becoming what in charitable terms might be called a motivational life coach though others might describe her as a cult leader. She’s determined to get Fluffy into an elite primary school so he can “win at the starting line,” a buzzword in the contemporary society which basically means engineering privilege for your child so they can elbow other kids out of the way before the race even starts. The irony is rammed home by the fact that Sia, who works as the family’s live-in nanny/housekeeper also has a daughter named “Fluffy” who is one of China’s left behind children living with her seemingly bedridden grandmother in the provinces while Sia is in the city earning money to support the family having apparently divorced her daughter’s father.

20 years previously, Sia’s mother had accused her lover of rape and had him sent to prison where he’s remained ever since having apparently gone along with the legal process in the mistaken belief Sia would eventually clear up this misunderstanding. She later later says the police wouldn’t let her and that she was never actually interviewed, but also continues to insist that they live in a “law-based society,” and nothing can be done without evidence. On his release, Shengli (Jiang Wu) comes straight to find his former lover in order to confirm that he did not in fact rape her and their relationship was consensual which she agrees it was. This determination is symbolic of his romanticism in continuing to believe in his dream of love despite all he’s been through, convincing himself he can start again with Sia while she continues to manipulate him with the almost certainly false promise of a happy joint future.

But then you can’t really blame her. A little way into the film, Sia is dressed in a white outfit very similar to the one worn by her boss when she goes to see Fluffy in a school play in which, at his own request, he played a tree. Sia is every bit as a accomplished and she has a warm and loving relationship with Fluffy which seems to elude his haughty mother. Later in the film she reveals that she came third in the national university exams but was prevented from going because she was born in a small rural province rather than the big city like her employer Mrs Mao. The fates of the two women are easily interchangeable depending on the circumstances of their birth while Mrs Mao continues to wield her privilege to ensure Fluffy can win at the starting line despite her resentment towards him for his lack of academic acumen or the things that denote conventional success in the modern China. Though he is cheerful and kind, she sees these qualities as actively harmful to his future success rather than embracing the little ray of sunshine he actively is.

Then again, Fluffy’s guilelessness also leaves him vulnerable which is why he cheerfully walks off with Shengli when he agrees to Sia’s kidnap plot and even rejoices in the grave-like pit they’ve dug to keep him in rechristening it as his underground fortress. He’s so nice that he doesn’t even realise the other kids are bullying him for being “stupid” and thinks they’re his friends, just happy to be included in the game. In this way, he and Shengli are alike, a pair of hapless fools living in a world that’s nowhere near as good as they think it is. The irony is that though Shengli perhaps begins to wake up to the realities of his relationship with Sia, his last wish for Fluffy is that he get into the fancy primary school and win at the starting line so he won’t end up like him. Suddenly it seems ironic that Shengli was a breakdancer because in the end he cannot break free of the prison that is the modern China. Filled with a darkly comic humour, the film is a fierce critique of the inequalities of the contemporary society and gentle advocation for the right to just be nice in world in which kindness has become a character flaw.

The Escaping Man screens July 26 as part of this year’s New York Asian Film Festival.