Humans place themselves above animals precisely because of their ability to communicate and work together to create complex plans that allow them to overcome their circumstances. Robbed of our speech, would we still say the same? Gen Nagao’s dialogue-free drama Choke (映画(窒息), Eiga Chissoku) takes place in a world in which language appears to have disappeared. Humans communicate only through gesture and are therefore prevented from explaining themselves fully, able to rely only on the vagueness of feeling to convey their thoughts and intentions.

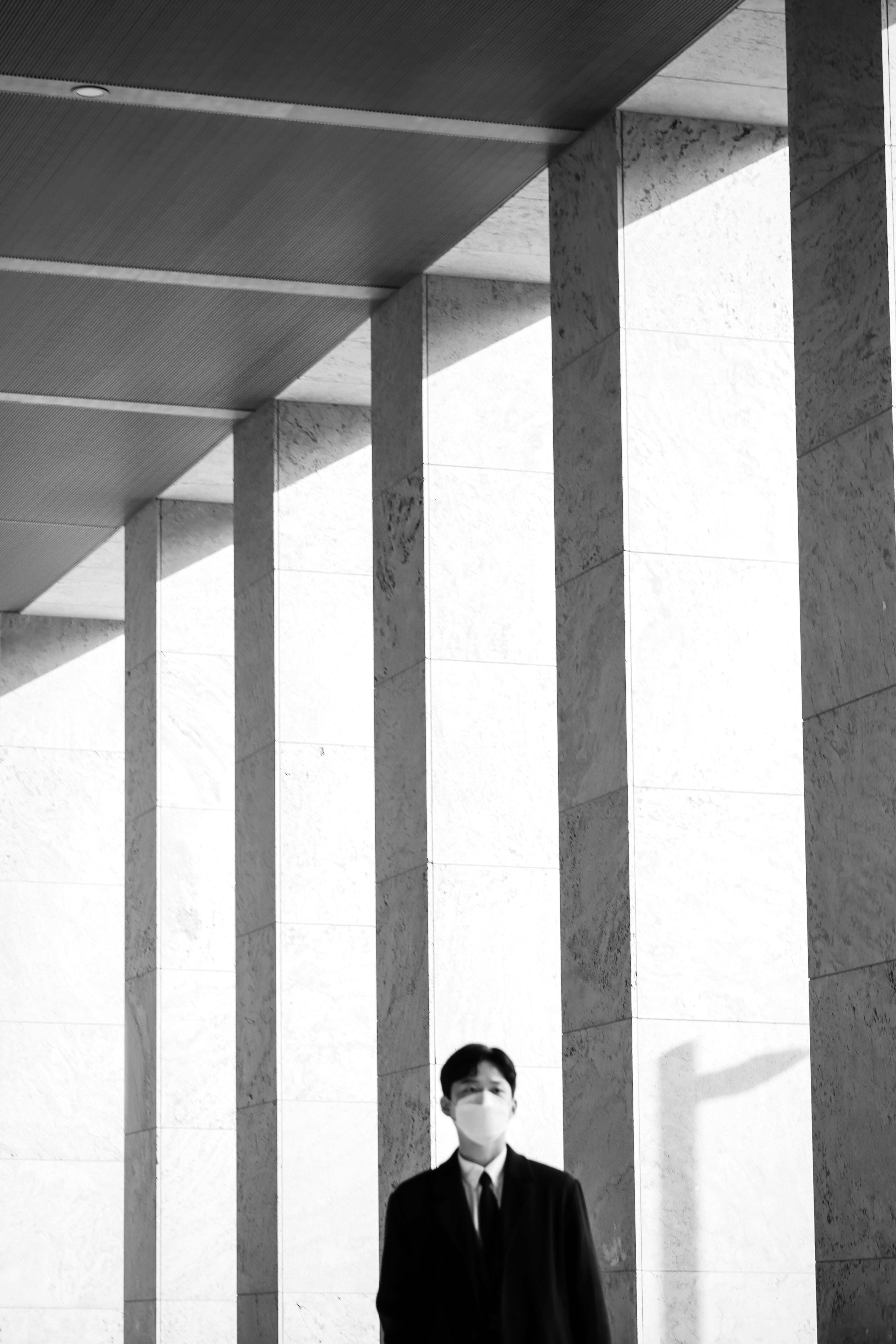

Yet we might not quite grasp this at first, because the heroine (Misa Wada) lives a solitary life in which she rarely needs to talk to anyone anyway. Shot in a crisp black and white, this appears to be some kind of near future, post-apocalyptic world in which even ancient technologies have largely been forgotten. The woman lives in a concrete structure, presumably a disused factory which is dotted with broken machinery that the woman largely ignores as she lives her simple and repetitive life of waking, fetching water, hunting, cooking and eating. We have no reason to think that she is unhappy for besides the occasional sigh, she simply gets on with her daily tasks and then goes to sleep seemingly unafraid of external threats.

But it is indeed male violence that punctures her world when she’s set upon by three men, seemingly an older man and his grown-up sons one of whom holds her still while the middle-aged man rapes her after breaking the magnifying glass she’d bought off a cheerful pedlar enraptured by the wonder of instant fire (well, while the sun shines at least). Her world becomes darker and she finds herself haunted by a shadowy figure that hovers over her as she sleeps. But then, her trap catches a young man (Daiki Hiba) whom she at first seems as if she’s going to kill and eat but later reconsiders and lets him go presumably calculating he poses no threat to her. The young man has a goofy grin and cheerful disposition, returning to bring the woman gifts and follow her around doing odd jobs before the pair develop a relationship and start living as a couple. The young man even devises a system of bamboo pipes to bring water from the brook so the woman won’t need to carry buckets back and forth anymore in a seeming rediscovery of technology born of his desire to make her life easier.

This more nurturing, protective kind of masculinity brings a new a dimension to her life but their harmonious days do not last long before male violence intrudes once again and proves a corrupting influence for the young man who seemingly becomes cruel and vengeful, though not toward the woman even as she begins to reconsider her relationship with him and if this kind of inhumanity is something she can tolerate in the idyll she’d crafted for herself before he arrived. Then again, in trying to deal with it is there something that becomes cruel or violent in herself in that wasn’t that way before even if doing so also makes her sad and leaves her lonely?

Until then she’d found only wonder in the natural world, repurposing the disused, man-made structures of the factory to make music in the rain and more problematically filled with childish glee when something wanders into her trap. But nature holds its dangers too even if there don’t appear to be any predators here besides man in the form of poisonous mushrooms easily mistaken for the edible kind. Even so, it’s violence that finally poisons her world. A senseless kind of violence that doesn’t seem to be about competition for resources, but only an animal lust and craving for dominance. If only they could communicate in a more concrete way perhaps it could be avoided, but then that doesn’t seem to have worked out that way for us who face such threats every day with words often ignored.

In any case, Nagao finally heads into a more abstract space as the woman seems to react to the abrupt halt of the film’s soundtrack followed by the removal not only of speech but sound from her world as is if she had lost her hearing. Her reality fractures and we can’t be sure she hasn’t just imagined anything that went before or that she has been targeted by some unseen supernatural or spiritual force for her transgressions leading to her exile from a disintegrating paradise. Obscure and haunting, the film nevertheless has a kind of cheerfulness in its innate absurdity captured in the lunking physicality of the actors who move with a cartoonish strangeness and exaggerate their facial expressions in a strenuous attempt to communicate in the absence of words. The message seems to be that in the end we ruin things for ourselves, either through violence or simply doing what we think is right but in the end may really be no different nor any better.

Motion Picture: Choke screened as part of this year’s JAPAN CUTS.

Original trailer (dialogue free)