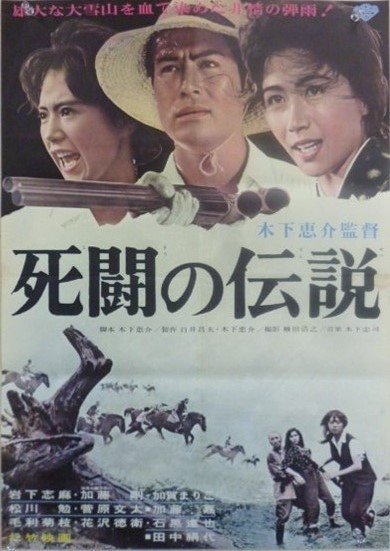

In 1951’s Boyhood, Kinoshita had painted a less than idealised portrait of village life during wartime. With pressure mounting ranks were closing, “outsiders” were not welcome. The family at the centre of Boyhood had more reasons to worry in that they had, by necessity, removed themselves from a commonality in their ideological opposition to imperialism but newcomers are always vulnerable when they find themselves undefended and without friends. 1963’s A Legend or Was It? (死闘の伝説, Shito no Densetsu, AKA Legend of a Duel to the Death) tells a similar story, but darker as a family of evacuees fall foul not only of lingering feudal mores but a growing resentment in which they find themselves held responsible for all the evils of war.

In 1951’s Boyhood, Kinoshita had painted a less than idealised portrait of village life during wartime. With pressure mounting ranks were closing, “outsiders” were not welcome. The family at the centre of Boyhood had more reasons to worry in that they had, by necessity, removed themselves from a commonality in their ideological opposition to imperialism but newcomers are always vulnerable when they find themselves undefended and without friends. 1963’s A Legend or Was It? (死闘の伝説, Shito no Densetsu, AKA Legend of a Duel to the Death) tells a similar story, but darker as a family of evacuees fall foul not only of lingering feudal mores but a growing resentment in which they find themselves held responsible for all the evils of war.

Beginning with a brief colour framing sequence, Kinoshita shows us a contemporary Hokkaido village filled with cheerful rural folk who mourn each other’s losses and share each other’s joys while shouldering communal burdens. A voice over, however, reminds us that something ugly happened in this beautiful place twenty years previously. Something of which all are too ashamed to speak. Switching back to black and white and the same village in the summer of 1945, he introduces us to Hideyuki Sonobe (Go Kato) who has just come home from the war to convalesce from a battlefield injury. Hideyuki’s engineer father went off to serve his country and hasn’t been heard from since, and neither has his brother who joined the air corp. His mother (Kinuyo Tanaka), sister Kieko (Shima Iwashita), and younger brother Norio (Tsutomu Matsukawa) have evacuated from Tokyo to this small Hokkaido village where they live in a disused cottage some distance from the main settlement.

The family had been getting by in the village thanks to the support of its mayor, Takamori, but relations have soured of late following an unexpected marriage proposal. Takamori’s son Goichi (Bunta Sugawara), a war veteran with a ruined hand and young master complex, wants to marry Kieko. She doesn’t want to marry him, but the family worry about possible repercussions if they turn him down. It just so happens that Hideyuki recognises Goichi and doesn’t like what he sees – he once witnessed him committing an atrocity in China and knows he is not the sort of man he would want his sister to marry, let alone marry out of fear and practicality. Hideyuki, as the head of the family, turns the proposal down and it turns out they were right to worry. The family’s field is soon vandalised and the police won’t help. When other fields meet the same fate, a rumour spreads that the Sonobes are behind it – taking revenge on the village on as a whole. The villagers swing behind Goichi, using the feud as a cover to ease their own petty grievances.

City dwellers by nature, the Sonobes have wandered into a land little understood in which feudal bonds still matter and mob mentality is only few misplaced words away. The village serves a microcosm of Japanese society at war in which Takamori becomes the unassailable authority and his cruel son the embodiment of militarism. Goichi embraces his role as a young master with relish, riding around the town on horse back and occasionally barking orders at his obedient peasants, stopping only to issue a beating to anyone he feels has slighted him – even taking offence at an innocuous folksong about a man who was rejected in love and subsequently incurred a disability. Despite all of that, however, few can find the strength to resist the pull of the old masters and the majority resolutely fall behind Goichi, willing to die for him if necessary.

As the desperation intensifies and it appears the war, far off as it is, is all but lost, a kind of creeping madness takes hold in which the Sonobes become somehow responsible for the greater madness that has stolen so many sons and husbands from this tiny village otherwise untouched by violence or famine. An embodiment of city civilisation the Sonobes come to represent everything the village feels threatened by, branded as “bandits” and blamed for everything from murder to vegetable theft. The central issue, one of a weak and violent man who felt himself entitled to any woman he wanted and refused to accept the legitimacy of her right to refuse, falls by the wayside as just another facet of the spiralling madness born of corrupted male pride and misplaced loyalties.

Kinoshita returns to the idyllic countryside to close his framing sequence, reminding us that these events may have been unthought to the level of myth but such things did happen even if those who remember are too ashamed to recall them. Tense and inevitable, A Legend or Was It? reframes an age of fear and madness as a timeless village story in which the corrupted bonds of feudalism fuel the fires of resentment and impotence until all that remains is the irrationality of violence.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

When AnimEigo decided to release Hideo Gosha’s Taisho/Showa era yakuza epic Onimasa (鬼龍院花子の生涯, Kiryuin Hanako no Shogai), they opted to give it a marketable but ill advised tagline – A Japanese Godfather. Misleading and problematic as this is, the Japanese title Kiryuin Hanako no Shogai also has its own mysterious quality in that it means “The Life of Hanako Kiryuin” even though this, admittedly hugely important, character barely appears in the film. We follow instead her adopted older sister, Matsue (Masako Natsume), and her complicated relationship with our title character, Onimasa, a gang boss who doesn’t see himself as a yakuza but as a chivalrous man whose heart and duty often become incompatible. Reteaming with frequent star Tatsuya Nakadai, director Hideo Gosha gives up the fight a little, showing us how sad the “manly way” can be on one who finds himself outplayed by his times. Here, anticipating Gosha’s subsequent direction, it’s the women who survive – in large part because they have to, by virtue of being the only ones to see where they’re headed and act accordingly.

When AnimEigo decided to release Hideo Gosha’s Taisho/Showa era yakuza epic Onimasa (鬼龍院花子の生涯, Kiryuin Hanako no Shogai), they opted to give it a marketable but ill advised tagline – A Japanese Godfather. Misleading and problematic as this is, the Japanese title Kiryuin Hanako no Shogai also has its own mysterious quality in that it means “The Life of Hanako Kiryuin” even though this, admittedly hugely important, character barely appears in the film. We follow instead her adopted older sister, Matsue (Masako Natsume), and her complicated relationship with our title character, Onimasa, a gang boss who doesn’t see himself as a yakuza but as a chivalrous man whose heart and duty often become incompatible. Reteaming with frequent star Tatsuya Nakadai, director Hideo Gosha gives up the fight a little, showing us how sad the “manly way” can be on one who finds himself outplayed by his times. Here, anticipating Gosha’s subsequent direction, it’s the women who survive – in large part because they have to, by virtue of being the only ones to see where they’re headed and act accordingly.