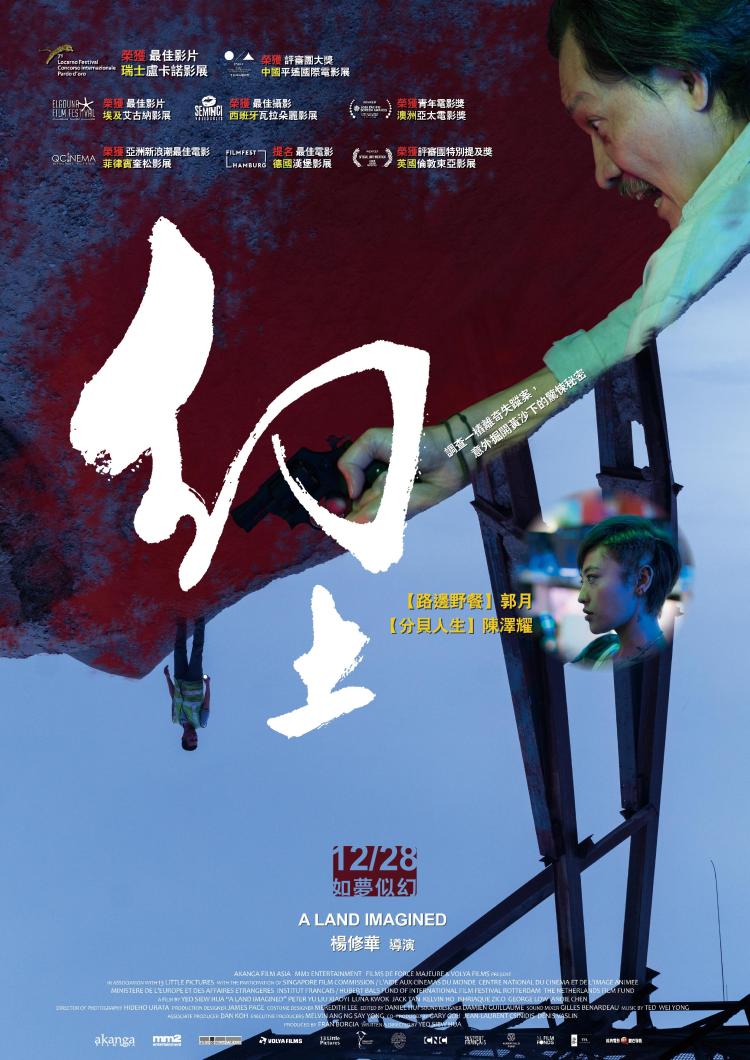

As the world gets bigger and smaller at the same time, it’s as well to be asking on whose labour these new lands are being forged. Yeo Siew Hua’s Locarno Golden Leopard winner A Land Imagined (幻土, Huàn Tǔ) attempts to do just that in digging deep into the reclaimed land that has made the island of Singapore, an economic powerhouse with a poor record in human rights, 22% bigger than it was in 1965. A migrant worker goes missing and no one really cares except for an insomniac policeman who dreams himself into a kind of alternate reality which is both existential nightmare and melancholy meditation on the rampant amorality of modern day capitalism.

As the world gets bigger and smaller at the same time, it’s as well to be asking on whose labour these new lands are being forged. Yeo Siew Hua’s Locarno Golden Leopard winner A Land Imagined (幻土, Huàn Tǔ) attempts to do just that in digging deep into the reclaimed land that has made the island of Singapore, an economic powerhouse with a poor record in human rights, 22% bigger than it was in 1965. A migrant worker goes missing and no one really cares except for an insomniac policeman who dreams himself into a kind of alternate reality which is both existential nightmare and melancholy meditation on the rampant amorality of modern day capitalism.

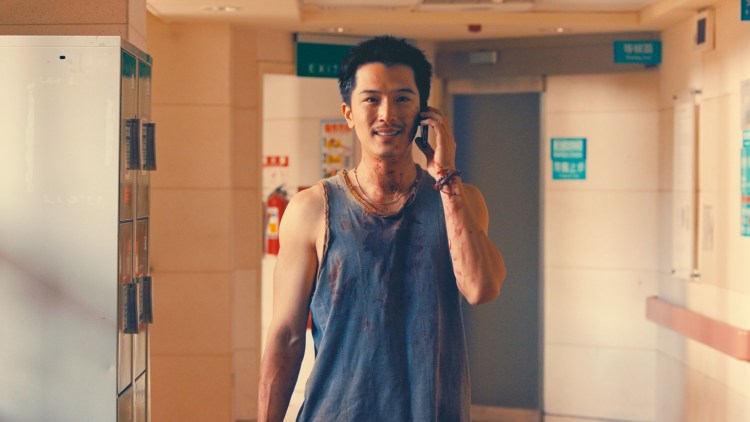

Lok (Peter Yu), a hangdog middle-aged detective, is charged with looking for Wang Bi Cheng (Liu Xiaoyi), a missing migrant worker from China. Just who it was that noticed Wang’s absence is only latterly explained and in suitably ambiguous fashion, but the fact remains that there is an empty space where a man named Wang used to be and Lok is the man charged with resolving that space no matter who might or might not be interested. We discover that Wang was injured on the job, almost sacked and then reprieved to drive the workers’ bus where he befriended a worker from Bangladesh, Ajit (Ishtiaque Zico), who later disappeared sending Wang on his own mirrored missing persons case in which he begins to suspect something very bad may have happened to his friend.

Despite his presumably long years on the force and world weary bearing, Lok is refreshingly uncynical for a police detective but apparently extremely naive about the city in which he lives. Stepping into the world of Wang Bi Cheng, he is shocked to discover that people live “like this” – several men crammed into in tiny bed bug infested rooms so brightly lit from outside that it’s difficult to believe that anyone gets any sleep at all. Wang, in any case, like Lok did not sleep and gradually migrated over to the 24hr internet cafe across the way where he developed a fondness for the spiky proprietress, Mindy (Luna Kwok), while repeatedly dying in videogames and being trolled by a mysterious messenger who may or may not have information about his missing friend.

Like Lok, Wang Bi Cheng cannot sleep but lives in a waking dream – one in which he envisages his own absence and the two police detectives who will search for him, not because they care but because it’s their job and they’re good at it. Men like Wang are the invisible, ghostly presence that makes this kind of relentless progress possible yet they are also disposable, fodder for an unscrupulous and uncaring machine. Asked if it’s possible that Wang and his friend Ajit simply left, the foreman’s son Jason (Jack Tan ) answers that it’s not because the company keeps the men’s passports, adding a sheepish “for their own protection, in case they lose them” on realising the various ways he has just incriminated himself.

Yeo opens with a brief and largely unrelated sequence of a young Chinese migrant worker climbing a tower in his bright orange overalls. Later Lok reads a newspaper report about this same man who tried to launch a protest in having been denied his pay and forced to endure dangerous and unethical working conditions. Meanwhile, Mindy the internet cafe girl, is forced to resort to taking money for sex acts in order to make ends meet. Like Wang, she dreams of escape, of the right to simply go somewhere else without the hassle of visas and passports. Wang jokes that the sand that built the reclaimed beach they are sitting on came from Malaysia, and that in a sense they have already crossed borders, offering to take Mindy away from all this (for a moment at least) in his (borrowed) truck but knowing that their escape is only a mental exercise in transcending the futility of their precarious existences.

Indeed, Yeo seems to be saying that Singapore itself is a “land imagined” – constantly creating and recreating itself with repeated images of modernity. One could even read its artificial territorial expansion as reshaping of its mental landscape while all this progress is dependent on the exploitation of wayfarers like Wang and Ajit wooed by the promises of wages higher than in their home countries but left with little protection and entirely at the mercy of their unscrupulous employers. Yet a strange kind of affinity arises between the lost souls of Lok and Wang, united in a common dreamscape born of sleeplessness and lit by the anxious neon of rain-drenched noir as they pursue their parallel quests, looking for each other and themselves but finding only elusive shadows of half-remembered men dreaming themselves out of existential misery.

A Land Imagined screens as part of the eighth season of Chicago’s Asian Pop-Up Cinema on March 20, 7pm at AMC River East 21 where director Yeo Siew Hua will be present for an introduction and Q&A.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

Chicago’s

Chicago’s  Fumi Nikaido stars as the cosseted son of a corrupt Tokyo Governor alongside pop star Gackt as a “mysterious transfer student” in Hideki Takeuchi’s adaptation of the popular ’80s manga.

Fumi Nikaido stars as the cosseted son of a corrupt Tokyo Governor alongside pop star Gackt as a “mysterious transfer student” in Hideki Takeuchi’s adaptation of the popular ’80s manga. Five young directors provide their visions of a near future Japan in an omnibus movie inspired by the Hong Kong original and produced by Hirokazu Koreeda.

Five young directors provide their visions of a near future Japan in an omnibus movie inspired by the Hong Kong original and produced by Hirokazu Koreeda.  Documentary exploring the experiences of early Japanese migrants along with their American-born children.

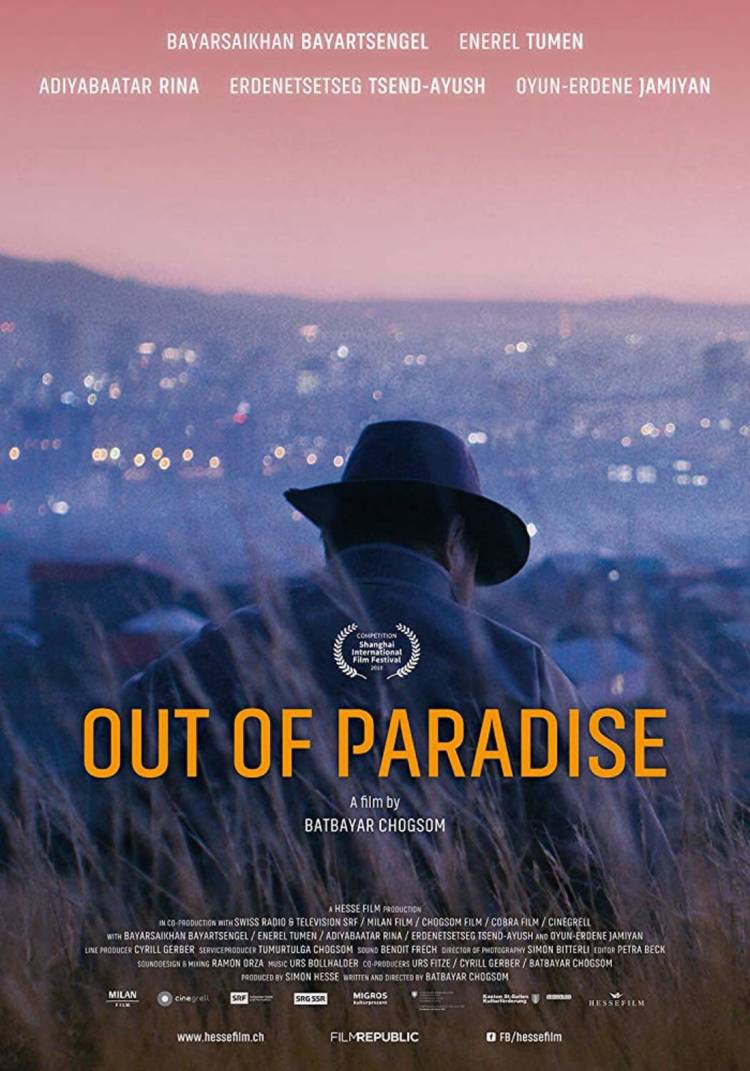

Documentary exploring the experiences of early Japanese migrants along with their American-born children. A man and his heavily pregnant wife make a perilous journey to the Mongolian capital in order to get a caesarian section but once there discover they are unable to cover the medical fees.

A man and his heavily pregnant wife make a perilous journey to the Mongolian capital in order to get a caesarian section but once there discover they are unable to cover the medical fees. Singaporean police officer Lok investigates the disappearance of migrant worker Wang in Yeo Siew-hua’s Locarno prize winning crime drama.

Singaporean police officer Lok investigates the disappearance of migrant worker Wang in Yeo Siew-hua’s Locarno prize winning crime drama. French/Cambodian animated co-production set during the Khmer Rouge revolution of 1975 in which a young mother searches for her four-year-old son who was taken away by the regime.

French/Cambodian animated co-production set during the Khmer Rouge revolution of 1975 in which a young mother searches for her four-year-old son who was taken away by the regime. A young man making a rare visit home to Malaysia on the death of an aunt is forced to reconnect with his estranged mother whom he left behind when he went to university in Hong Kong. Actress Nina Paw Hee-Ching will be present at the screening for an introduction and Q&A as well as to collect the Career Achievement Award.

A young man making a rare visit home to Malaysia on the death of an aunt is forced to reconnect with his estranged mother whom he left behind when he went to university in Hong Kong. Actress Nina Paw Hee-Ching will be present at the screening for an introduction and Q&A as well as to collect the Career Achievement Award. A young man whose brother has recently passed away makes a surprising discovery on the cell phone he left behind – the live streams of an elderly cab driver known as Granny.

A young man whose brother has recently passed away makes a surprising discovery on the cell phone he left behind – the live streams of an elderly cab driver known as Granny. A medical examiner investigating the death of a fisherman who self immolated to protest corporate giant TL Petrochemical uncovers a major conspiracy in Chuang Ching-shen’s crime thriller.

A medical examiner investigating the death of a fisherman who self immolated to protest corporate giant TL Petrochemical uncovers a major conspiracy in Chuang Ching-shen’s crime thriller. Documentary by Zhang Yang focussing on the studio of artist Shen Jian-hua in a remote village in Yunnan Province.

Documentary by Zhang Yang focussing on the studio of artist Shen Jian-hua in a remote village in Yunnan Province. Director Lu Qingyi follows the everyday lives of his parents over four years in the remote town of Dushan in southwest China.

Director Lu Qingyi follows the everyday lives of his parents over four years in the remote town of Dushan in southwest China. Canadian chemical engineer Wendy Fong ponders her future in the face of industry layoffs in this special presentation in collaboration with the Consulate General of Canada in Chicago.

Canadian chemical engineer Wendy Fong ponders her future in the face of industry layoffs in this special presentation in collaboration with the Consulate General of Canada in Chicago. Omnibus film set in a small hotel which becomes home to parents attempting to come to terms with the loss of their child, a couple trying to rekindle their marriage, a woman who insists on staying in her preferred room, and the substitute manager who invites his girlfriend over for the evening.

Omnibus film set in a small hotel which becomes home to parents attempting to come to terms with the loss of their child, a couple trying to rekindle their marriage, a woman who insists on staying in her preferred room, and the substitute manager who invites his girlfriend over for the evening. A young woman in a long distance relationship with a man from Nagoya decides to visit him when he drops out of contact only to discover he is engaged to someone else.

A young woman in a long distance relationship with a man from Nagoya decides to visit him when he drops out of contact only to discover he is engaged to someone else. A Lengger dancer looks back on his life as a tale of growing acceptance of sensuality lived against a turbulent political backdrop.

A Lengger dancer looks back on his life as a tale of growing acceptance of sensuality lived against a turbulent political backdrop. A 51-year-old married father begins to reconsider his life choices after the death of a friend, eventually coming to an acceptance of a transgender identity.

A 51-year-old married father begins to reconsider his life choices after the death of a friend, eventually coming to an acceptance of a transgender identity.

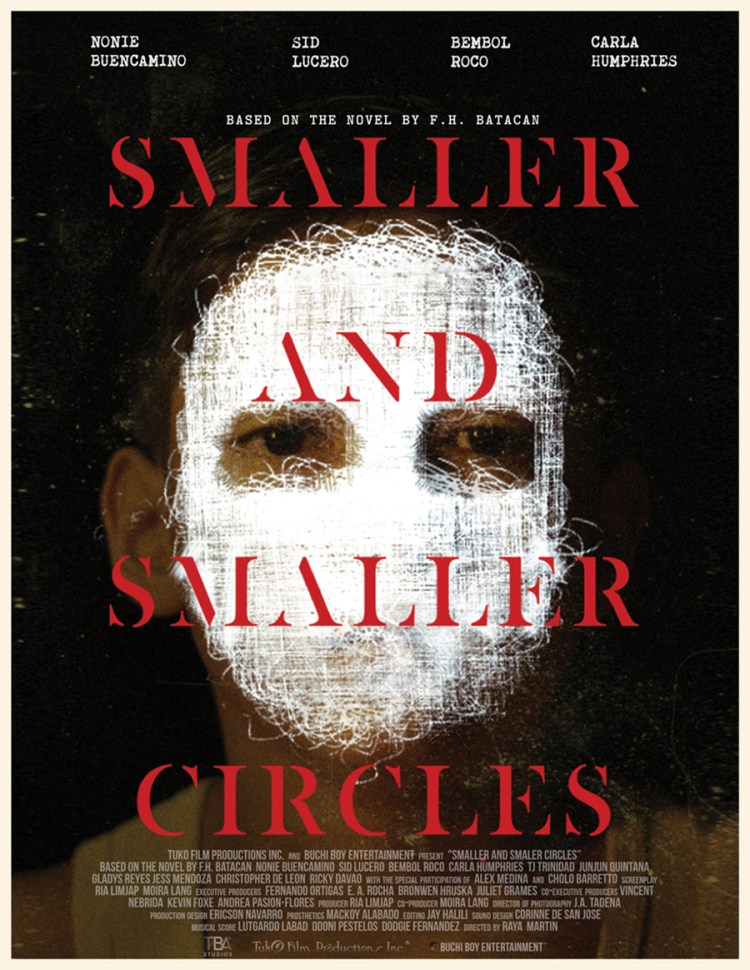

Raya Martin adapts the novel by F.H. Batacan in which two priests investigate a series of killings targeting young boys in the slums of Manila.

Raya Martin adapts the novel by F.H. Batacan in which two priests investigate a series of killings targeting young boys in the slums of Manila.

Chengxi’s dad has just died. He’d left the family sometime before and despite the best efforts of Chengxi’s mum, Chengxi knew perfectly well that it was to be with another man. The problem now is Chengxi’s dad has left everything to his new partner Jay and Chengxi’s mum is not at all happy about it…

Chengxi’s dad has just died. He’d left the family sometime before and despite the best efforts of Chengxi’s mum, Chengxi knew perfectly well that it was to be with another man. The problem now is Chengxi’s dad has left everything to his new partner Jay and Chengxi’s mum is not at all happy about it…