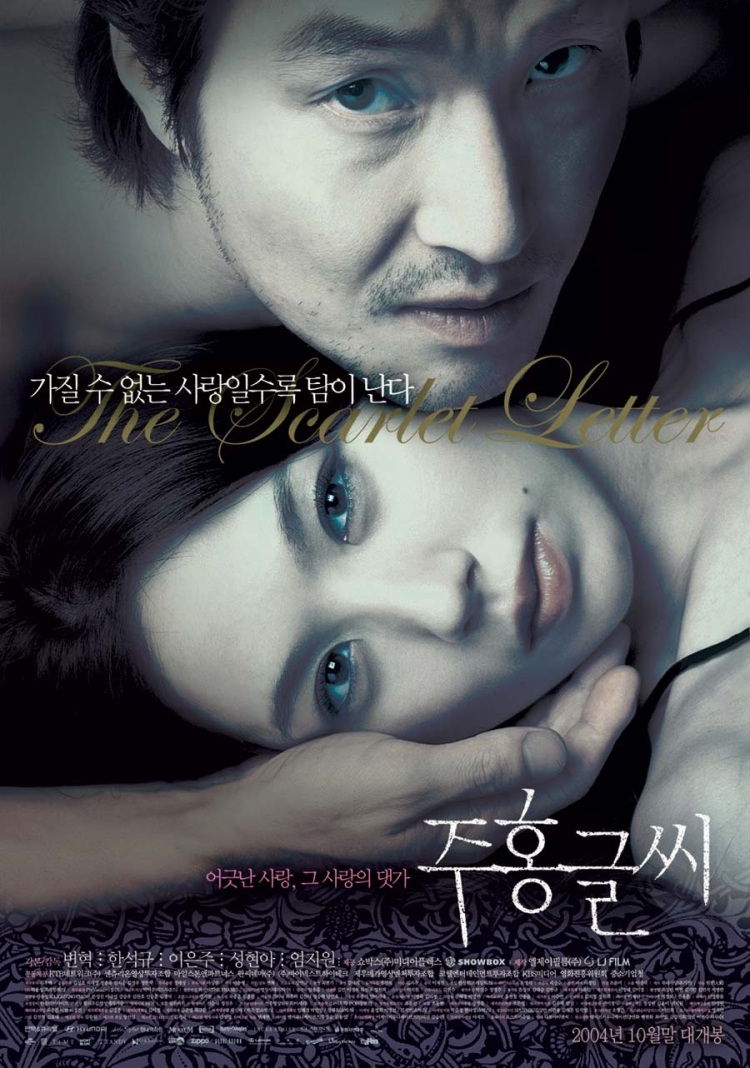

South Korea has long had a reputation for being among the most conservative of East Asian nations, perhaps because of a strong Christianising influence, but even so the fact that adultery was only fully decriminalised in 2015 is something of a surprise. Ironically enough the legislation was enacted in the defence of women who enjoyed few legal rights and would be left destitute if their husbands left them, suffering not only the humiliation and social stigma of divorce but also having no independent income and very little possibility of gaining one. Nevertheless it quickly became another tool of social control, branding “harlots” rather than protecting “wives”. Byeon Hyeok’s The Scarlet Letter (주홍글씨, Juhong Geulshi) was released in 2004, which is a whole decade before adultery was removed from the statue books, and draws inspiration from the book of the same name by Nathaniel Hawthorne in which a young woman becomes a social outcast after giving birth to an illegitimate child.

South Korea has long had a reputation for being among the most conservative of East Asian nations, perhaps because of a strong Christianising influence, but even so the fact that adultery was only fully decriminalised in 2015 is something of a surprise. Ironically enough the legislation was enacted in the defence of women who enjoyed few legal rights and would be left destitute if their husbands left them, suffering not only the humiliation and social stigma of divorce but also having no independent income and very little possibility of gaining one. Nevertheless it quickly became another tool of social control, branding “harlots” rather than protecting “wives”. Byeon Hyeok’s The Scarlet Letter (주홍글씨, Juhong Geulshi) was released in 2004, which is a whole decade before adultery was removed from the statue books, and draws inspiration from the book of the same name by Nathaniel Hawthorne in which a young woman becomes a social outcast after giving birth to an illegitimate child.

Cocksure policeman Ki-hoon (Han Suk-kyu) lives in a world of his own dominion. Married to the elegant concert cellist Su-hyun (Uhm Ji-won), Ki-hoon is also carrying on an affair with the bohemian nightclub singer Ga-hee (Lee Eun-ju). One fateful day he is called to the scene of a bloody murder. The owner of a photographer’s studio has been found with half his head caved in and the prime suspect is his wife, Kyung-hee (Sung Hyun-ah), who found the body. Once she’s had some time to recover from the shock, Kyung-hee offers up some possible evidence regarding a local photographer who may have been semi-stalking her – something which had caused tension between herself and her husband. The photographer claims Kyung-hee asked him to take the photos, and others besides, but denies he was romantically interested in her or that the couple had been having an affair.

The murder case floats in the background as Ki-hoon’s personal life spirals ever more out of control. Both Su-hyun and Ga-hee are pregnant with his child and it seems inevitable the affair will be exposed. Ki-hoon fears this not out of guilt in causing emotional harm to one or both of his women, but out of a sense that it will be very annoying, inconvenient, and burdensome for him. When his wife does eventually confront him about the affair, Ki-hoon’s response is to ignore it and carry on as normal by acting excited about the baby as if to remind Su-hyun that she is already tied to him and it will be almost impossible for her to leave. Meanwhile, he refuses to give up Ga-hee whose mental state seems to be fracturing under the intense pressure of her need for Ki-hoon and his continuing disregard for the feelings of others.

Ki-hoon is a classic noir hero, wading into a morass of moral ambiguity and hurtling headlong towards an existential reckoning. A late, yet fantastically obvious, twist offers another perspective which the film has no time to expand on so caught up is it in the moral ruining of Ki-hoon in suggesting that oppressive social codes have in some way contributed to this intense situation, forcing three people into an uncomfortable love triangle where everyone has ended up with the wrong partner. Byeon does, however, choose to emphasise “morality” in lending a spiritual slant to Ki-hoon’s fall rather than choosing to attack the social oppression of Korea’s intensely conservative culture in which all the power was in Ki-hoon’s hands (even if he uses it to ruin himself, later left in a state of spiritual emptiness filled only with guilt and shame).

The reckoning comes in a literal evocation of Ki-hoon’s claustrophobic love life in which he finds himself trapped in an inescapable black hole, waiting to find out if he will be released or condemned to suffer an eternity of pain for his various transgressions. Byeon never quite manages to marry his higher purpose to the noir narrative, leaving his avant-garde final set piece out of place in an otherwise straightforward thriller while his final twist falls flat in retreading well worn genre cliches. Frank in terms of its depiction of sex and nudity, The Scarlet Letter takes on an anti-erotic quality, painting its various scenes of actualised sex as passionless acts of compulsion with only those of fantasy somehow imbued with colour and light though its melancholy conclusion suggests even these may carry a heavy price.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

Review of Hur Jin-ho’s The Last Princess first published by

Review of Hur Jin-ho’s The Last Princess first published by  Review of Lee Il-hyeong’s A Violent Prosecutor first published by

Review of Lee Il-hyeong’s A Violent Prosecutor first published by