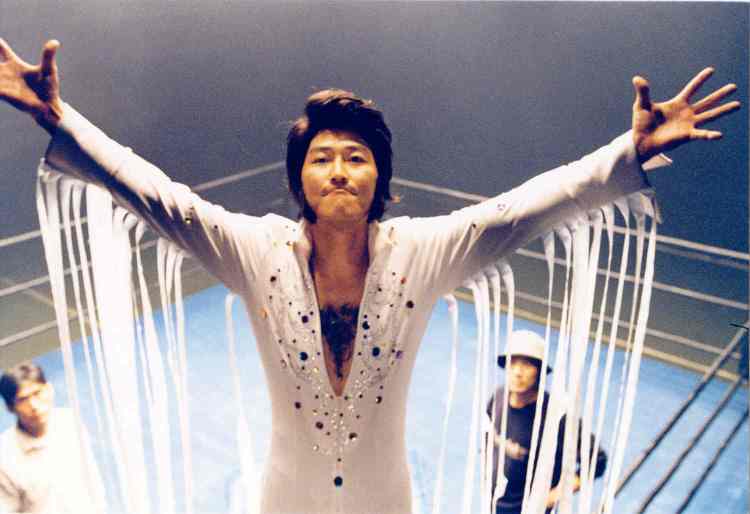

“Even though disappointed, do not lose hope” reads a piece of graffiti in the closing moments of Steve Chan Chi-fat’s nostalgic coming-of-age drama Weeds on Fire (點五步). Though touted as a baseball movie, as incongruous as that may sound given that the sport is a niche interest in contemporary Hong Kong, Chan’s strangely hopeful if quietly melancholy tale of ‘80s Sha Tin is bookended by scenes of the present day city in the midst of the Umbrella Movement protests the story the hero wants to offer seemingly intended for an audience of dejected youngsters as confused and disappointed as he once was in order to encourage them that what’s important isn’t winning or losing but staying the course and gaining the confidence to take the first step.

Now in his mid-40s, Lung (Lam Yiu-sing) casts his mind back to the Hong Kong of 1984 when he lived on a rundown council estate in Sha Tin and attended a high school with a less than stellar academic record. A shy and nerdy boy, he was often bullied but always had childhood friend Wai (Tony Wu Tsz-tung), physically imposing and with a confident swagger, at his back. When the city comes up with additional funding for schools to use in the promotion of sport their enterprising headmaster Lu Kwong-fai (Liu Kai-chi) hatches on the idea of starting the region’s very first local high school baseball team, recruiting both Wai and Lung in the hope of teaching them teamwork and discipline. Nevertheless, being teammates begins to place a strain on their friendship and it becomes clear that the boys are destined for different paths. Wai quits the team in a huff and leaves school, mooching round in pool bars and hanging out with triads while Lung steps up to the plate but is troubled by the loss of his friendship and the fracturing relationship between his unhappily married parents.

Chan somewhat unsubtly ties Lung’s personal development to that of Hong Kong as he finds himself coming of age in era of anxiety. The world is literally changing around him, 1984 being as says the year that the redevelopment of Sha Tin began in earnest while it also marked the signing of the Sino-British Declaration paving the way for the transfer of power in the 1997 Handover. A young man, Lung wants to “change” himself in that he longs for the confidence to ask out a young woman he’s developed a crush on but is too shy and disappointed in himself for doing nothing when witnessing her being harassed by a drunken creep in the lift of the apartment block where they both live. Yet in other ways change frightens him and really he wants everything to stay the same believing that saying nothing will maintain the status quo only to realise that there are situations over which he has no real control.

His headmaster and coach of the baseball team Lu admits that he set Wai and Lung against each other in order to encourage him to come out from his friend’s shadow embracing his own identity and discovering a sense of self-confidence. Yet Lung continues to struggle, a little lost unable to find clear direction in his life while everything changes around him occasionally consumed by a sense of despair as perhaps are the young protestors in believing their movement has failed. In baseball what he realises that it isn’t about winning or losing but having the confidence to step up to the plate, subtly telling the protestors to hang in there because there’s still time to turn this around. “I never said we had to win”, inspirational coach Lu reminds the boys, “but I did say never give up!”.

Loosely based on the real life story of the Shatin Martins though as the closing credit reel reveals the original team were primary school children rather than high schoolers, Chan shifts away from sporting drama towards the more familiar youth movie metaphor of two former friends heading in different directions, the good boy knuckling down while the “bad” becomes a victim of his own hotheaded arrogance even if managing to repair his fractured friendship with Lung before tragedy strikes. Filled with memories of Handover anxiety and a healthy dose of ‘80s nostalgia, the film’s incongruous jauntiness is perhaps at odds with the gravity of the tale though that is perhaps itself part of the message the older Lung has for the young. “This is the city where I grew up. It’s become increasingly unfamiliar” he laments striding through streets filled with tents occupied by student protestors, sympathising with their cause while offering them a note of melancholy hope in his own, sometimes painful, tale of finding his feet in a changing Hong Kong.

Weeds on Fire streams in Poland until Nov. 29 as part of the 15th Five Flavours Film Festival.

Original trailer (English subtitles)