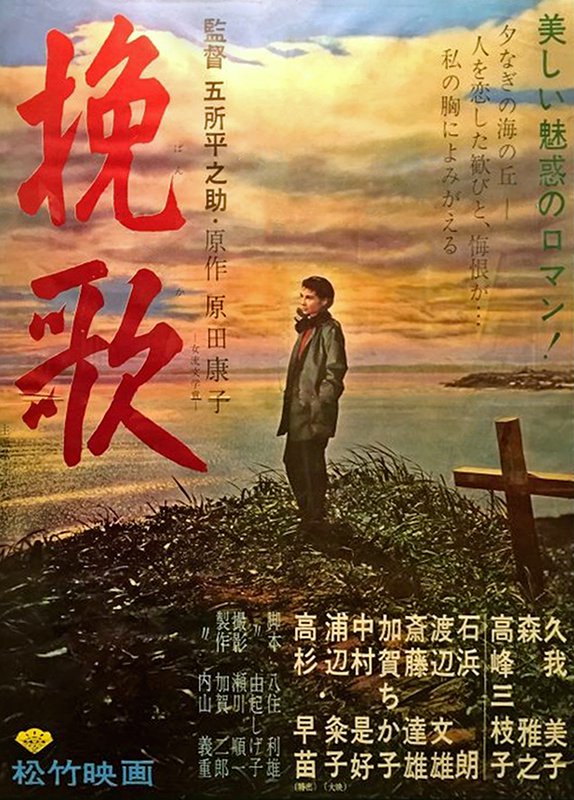

Heinosuke Gosho is perhaps among the most neglected Japanese directors of the “golden age”. A pioneer of the “shomingeki”, Gosho’s work is marked by a profound humanism but also a refusal to reduce the complexity of human emotions to the superficially immediate. Elegy of the North (挽歌, Banka) takes him much further in the direction of standard melodrama than he would usually venture, echoing contemporary American or European romantic dramas filled with soaring scores and moments of intense emotion bridged by long periods of restraint and repression. Yet it is also among the most psychologically complex of Gosho’s narratives, telling stories of death and rebirth in place of the usual coming of age and first heartbreak for which the genre is so well loved. In Reiko (Yoshiko Kuga) he presents us with a heroine we can’t be sure we like and certainly are not intended to approve of even as we sympathise with her pain and long for an end to her (often self inflicted) suffering.

Heinosuke Gosho is perhaps among the most neglected Japanese directors of the “golden age”. A pioneer of the “shomingeki”, Gosho’s work is marked by a profound humanism but also a refusal to reduce the complexity of human emotions to the superficially immediate. Elegy of the North (挽歌, Banka) takes him much further in the direction of standard melodrama than he would usually venture, echoing contemporary American or European romantic dramas filled with soaring scores and moments of intense emotion bridged by long periods of restraint and repression. Yet it is also among the most psychologically complex of Gosho’s narratives, telling stories of death and rebirth in place of the usual coming of age and first heartbreak for which the genre is so well loved. In Reiko (Yoshiko Kuga) he presents us with a heroine we can’t be sure we like and certainly are not intended to approve of even as we sympathise with her pain and long for an end to her (often self inflicted) suffering.

Walking along the smoking volcanic soil of frozen Hokkaido, Reiko offers us the first of many voiceovers in which she tells us about her left arm – withered and almost numb due to childhood arthritis. When her withered arm is bitten by a dog, Nellie, owned by a melancholy architect, Katsuragi (Masayuki Mori), she barely feels it but Katsuragi is mortified. “She’s never bitten anyone before”, he tells Reiko by way of explanation, “I’ve never been bitten before”, Reiko fires back but bitten she certainly has been. Captivated by the idea of Katsuragi, she doesn’t immediately take him up on the offer of coming to his house and possibly adopting a puppy but catches sight of him around town and then decides to pay him a visit. He isn’t in, but Akiko (Mieko Takamine), his wife, is. Reiko didn’t want to see Katsuragi’s wife so she makes a speedy escape.

Having caught sight of Akiko, Reiko is equally intrigued. Akiko, as Reiko discovers, is having an (unhappy) affair with a much younger medical student, Tatsumi (Fumio Watanabe). Failing to read the emotional landscape of this sorry scene, Reiko regards this information as a juicy piece of gossip in her ongoing campaign to win over Katsuragi. She spies on the lovers, childishly eavesdropping on them in a local cafe, even suddenly delivering their coffee for them so she can get a proper look at Akiko – not that she really sees her or the distraught look on her face, she merely observes her rival – the wicked woman who has betrayed her beloved Katsuragi.

Reiko is constantly berated by her father and grandmother for her unwomanliness. Compared with the typical Japanese woman of the time and particularly with the stoic yet miserable Akiko, Reiko can certainly be thought unusual. Dressing in androgynous loose trousers, polo neck jumper and overcoat, without makeup and with unkempt hair, her aesthetic is one of rambunctious child or rebellious teenager. Her habit of throwing out awkward, inappropriate questions at first seems like childish ineptness but later seems calculated to unbalance. She is often cruel, perhaps deliberately so, but then remorseful (if only for selfish reasons). Though Reiko seems to feel that it’s her disability that marks her out as an outcast, unfit for marriage or a “normal” life, her family appear much more concerned with her unconventional rejection of femininity in her boldness, masculine dress, and refusal to learn the traditionally feminine crafts of housework and cookery so necessary to becoming the ideal wife.

What Reiko sees in Akiko is an image of her idealised self – beautiful, poised, elegant, and the wife of Katsuragi. As part of her nefarious plan, Reiko decides to “befriend” Akiko while Katsuragi is away on a business trip. What she never expected is that she would come to genuinely care for both Akiko and the couple’s small daughter Kumiko (Etsuko Nakazato), making her position as a potential home wrecker impossible. Reiko’s father blames himself for her unwomanliness, having raised her alone after his wife died, denying her of a maternal influence from whom she would have learned all the essentials of femininity which she now seems to lack. Akiko, a few years older, becomes both friend and surrogate mother – Reiko even begins calling her “Mamma” just as Kumiko does. Akiko’s distant poise begins to thaw when Reiko crawls in through her door one night after contracting pneumonia. Nursing Reiko as a mother would brings the two women closer together but it also unwittingly drives them apart in deepening Reiko’s sense of guilt in being torn between two loves in the knowledge that she must destroy one of them or herself.

Akiko, the tragic heroine of the piece, remains a cypher precisely because of her adherence to the rules of traditional femininity. Reiko is first drawn to her because of her sad smile – something she later brings up again in their fiercely undramatic yet heartrending parting scene as Reiko tries to undo the harm she has just done only for Akiko to mildly reject her by instructing her that she needs to take better care of herself. Her relationship with Katsuragi appears to have floundered and, trapped in a lonely marriage, Akiko has found herself in an emotionally draining entanglement with a younger man whose life she fears she is ruining. Tatsumi, needled, is irritated by Reiko’s buzzing around Akiko, asking her an awkward question of his own in accusing her of being a lesbian, to which Reiko gives one of her infuriately barbed replies with “call it what you want”. Reiko’s intentions probably do not run that way (at least consciously), so much as she longs for the love and affection she missed out on after losing her mother at such a young age. Akiko, however, may see things differently. Her life appears lonely, and her friendship with Reiko, whom she brands “reckless yet somehow cheerful” (again, like an infuriating child), is one of its few bright spots. The betrayal is not so much that Reiko has slept with her husband, but that Reiko has deliberately ruined their friendship by exposing it as a cruel ruse in the most wounding of ways. The last time we see Akiko, she is wearing the necklace that Reiko gave to her – a sure sign that her final decision is, in someway, taken on Reiko’s behalf.

Reiko’s tragedy is that her intense self loathing which she attributes to her withered arm, leads her to suspect each act of kindness is only one of pity and that no one can truly love her, they’re just overcompensating because of her “deformity”. At the beginning of the film she asks herself if her mind is as warped as her body. Her actions are often “warped”, as in she works against herself and ultimately destroys the very thing she wanted most yet there is a kind of settling that occurs through her interactions with Akiko. In the final sequence, Reiko has shed her dowdy, dark coloured, worn trousers and jumpers for an elegant skirt and blouse, and has learned to accommodate a certain level of domesticity. Even if she is merely echoing Akiko, Reiko has at least attempted to move forward in exploring the areas of femininity she had hitherto rejected outright. That it is not to say her “unusual” nature is tamed in favour of conforming to social norms, merely that a side of herself which she had decided to keep locked has been opened up for examination (and may then be rejected with greater self knowledge). Elegy of the North lives up to its name in singing a long and painful song of mourning, but Gosho ends on a note of hopeful, in pained, optimism for his contrary heroine, literally forced to move past the scene of her crime towards a possibly happier future.

Screened at BFI as part of the Women in Japanese Melodrama season.

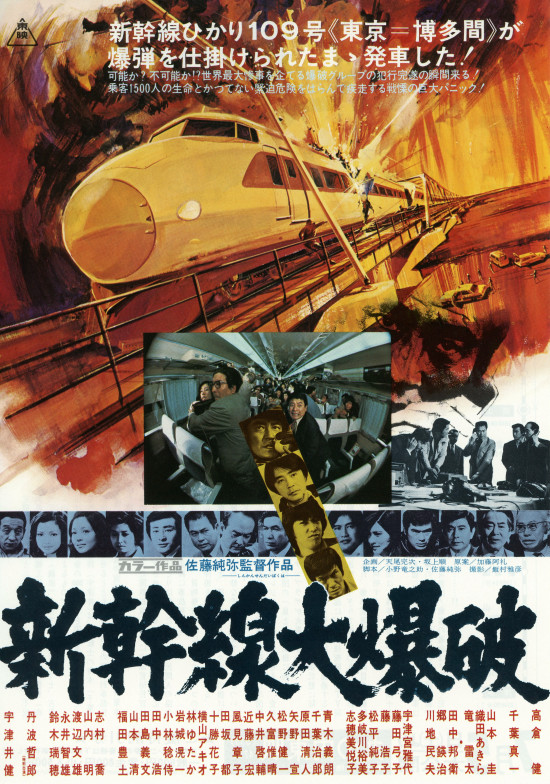

For one reason or another, the 1970s gave rise to a wave of disaster movies as Earthquakes devastated cities, high rise buildings caught fire, and ocean liners capsized. Japan wanted in on the action and so set about constructing its own culturally specific crisis movie. The central idea behind The Bullet Train (新幹線大爆破, Shinkansen Daibakuha) may well sound familiar as it was reappropriated for the 1994 smash hit and ongoing pop culture phenomenon Speed, but even if de Bont’s finely tuned rollercoaster was not exactly devoid of subversive political commentary The Bullet Train takes things one step further.

For one reason or another, the 1970s gave rise to a wave of disaster movies as Earthquakes devastated cities, high rise buildings caught fire, and ocean liners capsized. Japan wanted in on the action and so set about constructing its own culturally specific crisis movie. The central idea behind The Bullet Train (新幹線大爆破, Shinkansen Daibakuha) may well sound familiar as it was reappropriated for the 1994 smash hit and ongoing pop culture phenomenon Speed, but even if de Bont’s finely tuned rollercoaster was not exactly devoid of subversive political commentary The Bullet Train takes things one step further. When it comes to period exploitation films of the 1970s, one name looms large – Kazuo Koike. A prolific mangaka, Koike also moved into writing screenplays for the various adaptations of his manga including the much loved Lady Snowblood and an original series in the form of Hanzo the Razor. Lone Wolf and Cub was one of his earliest successes, published between 1970 and 1976 the series spanned 28 volumes and was quickly turned into a movie franchise following the usual pattern of the time which saw six instalments released from 1972 to 1974. Martial arts specialist Tomisaburo Wakayama starred as the ill fated “Lone Wolf”, Ogami, in each of the theatrical movies as the former shogun executioner fights to clear his name and get revenge on the people who framed him for treason and murdered his wife, all with his adorable little son ensconced in a bamboo cart.

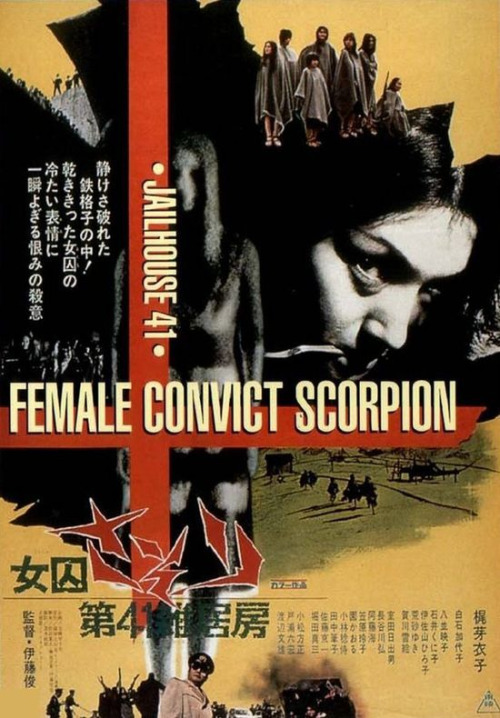

When it comes to period exploitation films of the 1970s, one name looms large – Kazuo Koike. A prolific mangaka, Koike also moved into writing screenplays for the various adaptations of his manga including the much loved Lady Snowblood and an original series in the form of Hanzo the Razor. Lone Wolf and Cub was one of his earliest successes, published between 1970 and 1976 the series spanned 28 volumes and was quickly turned into a movie franchise following the usual pattern of the time which saw six instalments released from 1972 to 1974. Martial arts specialist Tomisaburo Wakayama starred as the ill fated “Lone Wolf”, Ogami, in each of the theatrical movies as the former shogun executioner fights to clear his name and get revenge on the people who framed him for treason and murdered his wife, all with his adorable little son ensconced in a bamboo cart. Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41 (女囚さそり第41雑居房, Joshu Sasori – Dai 41 Zakkyobo) picks up around a year after the end of

Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41 (女囚さそり第41雑居房, Joshu Sasori – Dai 41 Zakkyobo) picks up around a year after the end of

Things take a slight detour in the third of the Outlaw series this time titled “Heartless” (大幹部 無頼非情, Daikanbu Burai Hijo). Rather than picking up where we left Goro – collapsed on a high school volleyball court, it’s now 1956 and we’re with a guy called “Goro the Assassin” but it’s not exactly clear is this is a side story or perhaps an entirely different continuity for the story of the noble hearted gangster we’ve been following so far. The only constant is actor Tetsuya Watari who once again plays Goro Fujikawa but in an even more confusing touch the supporting characters are played by many of the actors who featured in the first two films but are actually playing entirely different people….

Things take a slight detour in the third of the Outlaw series this time titled “Heartless” (大幹部 無頼非情, Daikanbu Burai Hijo). Rather than picking up where we left Goro – collapsed on a high school volleyball court, it’s now 1956 and we’re with a guy called “Goro the Assassin” but it’s not exactly clear is this is a side story or perhaps an entirely different continuity for the story of the noble hearted gangster we’ve been following so far. The only constant is actor Tetsuya Watari who once again plays Goro Fujikawa but in an even more confusing touch the supporting characters are played by many of the actors who featured in the first two films but are actually playing entirely different people…. Masaki Kobayashi is still not enamoured with the new Japan by the time he comes to make Black River (黒い河, Kuroi Kawa) in 1957 which proves his most raw and cynical take on contemporary society to date. Set in a small, rundown backwater filled with the desperate and hopeless, Black River is a tale of ruined innocence, opportunistic fury and a nation losing its way.

Masaki Kobayashi is still not enamoured with the new Japan by the time he comes to make Black River (黒い河, Kuroi Kawa) in 1957 which proves his most raw and cynical take on contemporary society to date. Set in a small, rundown backwater filled with the desperate and hopeless, Black River is a tale of ruined innocence, opportunistic fury and a nation losing its way.