Park Chung-hee kept a tight rein on cinema which he saw as an important political tool and means of communication. That’s not to say, however, that criticising his authoritarian regime was impossible, but that criticism was often expressed in unexpected or abstract ways. The debut film of Hollywood-trained director Ha Gil-jong, The Pollen of Flowers (화분, Hwabun), was adapted from a novel by Yi Hyoseok that was published in 1939 when Korea was under Japanese rule but now speaks directly to the contemporary era as a young man and woman long for escape from the oppressive atmosphere of the “Blue House”.

The Blue House is the name for the residence of Korea’s president and where Park Chung-hee lived at the time, but within the context of the film, it’s inhabited by the mistress of a wealthy businessman, Se-ran (Choi Ji-hee), and her younger sister, Mi-ran (Yoon So-ra). The relationship between the sisters is, however, much more like mother and daughter with Se-ran repeatedly stating that Mi-ran is “everything” to her and that she must grow up to become a “great woman”. The slightly uncomfortable implication is that she is encouraging a possible relationship between Mi-ran and her patron Hyeon-ma (Namkoong Won) or at least that by “great woman” she means Mi-ran should be the partner of a great man who moves within their social circles. Ominously, however, the film opens with Mi-ran discovering that all the fish in their pond have died making it clear that the water here is poisoned and the atmosphere rancid.

It’s not exactly clear how old Mi-ran is intended to be, only that Se-ran had been worried that hadn’t yet started menstruating. She’s spent her entire life in the cosseted environment of the Blue House and knows nothing of the world outside. That she gets her period for the first time when her father brings his secretary/secret lover Dan-ju (Hah Myung-joong) to the house suggests that she has, in a sense, been liberated by his arrival. For whatever reason, Se-ran had tried to warn her off him. She appears jealous while implying that Dan-ju is a dangerous social climber who threatens the integrity of her household. Mi-ran replies that you shouldn’t judge someone because of their background, but in a fit of pique also refers to Dan-ju as a “servant” which hurts both his feelings and his male pride.

But Dan-ju himself is something of a cypher whose motivations are often unclear. Having grown up working class, he’s risen in the world through complicity with Hyeon-ma’s authoritarian rule. As Se-ran says, Hyeon-ma is infatuated with him but perhaps more as a symbol of his overall control. He reminds Dan-ju that he controls his future and repeatedly asks him if he wants to go back to his old life of being a “scumbag” not quite realising that Dan-ju may have become fed up with his degradation and no longer thinks this kind of success is worth it. Hyeon-ma refers to Dan-ju as his “dream and ambition,” even going so far as to say he’d like to start a new life with him, though this is obviously not something that would be considered publicly acceptable in the Korea of the early 1970s. The film is often referred to as the first to depict a same-sex relationship, but it’s one motivated more by power than by love. It’s not clear if Hyeon-ma is so convinced that Mi-ran is completely safe with Dan-ju because he believes him to be interested only in men, or if he is certain that his control over him is absolute, while Dan-ju may not actually be interested in men at all and is only submitting himself to Hyeon-ma’s attentions in return for social advancement.

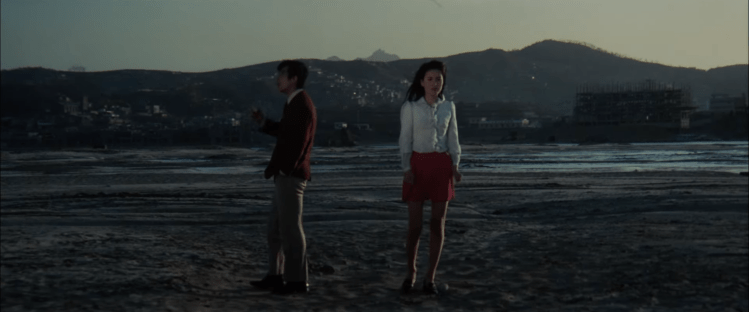

What he comes to represent for each is freedom. After running away, Mi-ran explains that she was happy with her life within the Blue House, in other words under authoritarianism, because it treated her well and so she could think of no other happiness. But meeting Dan-ju has shown her that happiness is possible outside of it. Love is a force that threatens the social order, and now Mi-ran resents her tightly controlled life and longs for the freedom Dan-ju represents over the patriarchal oppression represented by Hyeon-ma to which Se-ran has wholly submitted herself. Now that she’s committed to the regime, she cannot permit Mi-ran to leave it and tries to convince her to study music abroad and date an international pianist who could help career. Hyeon-ma, meanwhile, reacts in jealousy and frustration. He beats Dan-ju and throws him in his shed echoing the torture and imprisonment of dissidents that took place under Park’s regime.

As time passes, however, something evidently goes wrong with Hyeon-ma’s business causing him to flee in a hurry abandoning Se-ran and Mi-ran to their fates. The ominous maid who has been dropping rats through their windows, eventually tries to release Dan-ju with whom she has some kind of intimate connection, with the consequence that he haunts the mansion like a ghost. Mi-ran appears to have reassimilated, dancing with another man while wearing what looks very like wedding a dress, but her desire for freedom is reawakened by Dan-ju’s return. The house itself is then stormed by the revolutionary force of Hyeon-ma’s creditors who are not exactly noble avengers. They raid the place looting his possessions to get back what they’re owned, even going so far as to cut off Se-ran’s finger to take her ring and pulling out her gold teeth. The message seems to be that the dictator will probably get away (Park didn’t, he was assassinated by the head of his own security forces), but a heavy price will be paid for complicity when the regime falls, as all regimes eventually do.