Is it possible to be both married and personally and artistically fulfilled? Marriage hangs over Kiwa (Fujiko Yamamoto) like a looming cage in Kozaburo Yoshimura’s sensuous melodrama Undercurrent (夜の河, Yoru no Kawa, AKA Night River). Scripted not by his regular writer Kaneto Shindo but frequent Mikio Naruse collaborator Sumie Tanaka adapting a novel by Hisao Sawano, the film finds its heroine caught between tradition and modernity while struggling to maintain her position as an independent woman and rightful heir to her father’s kimono dyeing business.

Everyone also keeps telling her that kimono itself is dying out, a relic of a bygone past now that everyone wears Western dress. Even Kiwa’s younger sister Miyoko (Michiko Ono) dresses exclusively in Western fashions and moves to Tokyo on her marriage. An ancient capital, Kyoto is the centre of historical elegance and the last bastion of these “outdated ideals”, yet several shops in their area have closed recently and people do things differently now. A wealthy woman comes to the shop with some fabric directly, cutting out the middlemen and haggling for a discount while cheerfully asking for her cab fare to be covered when Kiwa refuses the job. The young man they’ve taken in as an apprentice, Toshio, leaves to work in an electric factory complaining that “master” and “apprentice” are outdated concepts and that it’s against the Labour Law to force him to work overtime. Kiwa’s father Yujiro (Eijiro Tono), meanwhile, thinks this is just an expression of Toshio’s lack of commitment and that it’s only right that an apprentice should be applying himself to learning his craft every waking moment of the day.

He was after all once an apprentice himself, but is both proud that his daughter has surpassed him in skill and guilty, fearful that Kiwa has sacrificed her own life and happiness to devote herself to kimono dyeing which is why she has never married. On one level, he’s happy if she’s happy and willing to leave marriage up to her, but also wary of the social censure of the neighbours including his kimono dyeing mentor who gives him a telling-off for his failure as a father to find a match for his daughter. When rumours arise that Kiwa has entered an affair with a married professor, the lady who helped Yujiro get started in business more or less tells him he should get her married to keep her in line. If hadn’t been for the war, she says, Kiwa would have been safely married off long ago and would probably have a gaggle of children to look after which would obviously prevent her from pursuing her art as a kimono dyer though the lady herself has obviously gone on working.

Kiwa is drawn Takemura (Ken Uehara ) firstly because he’s wearing a tie that features one of her signature dyes which implies some kind of affinity between them. That the fact that he was touring a Nara temple alone with his daughter may have suggested he was a widower, though in truth Kiwa always knew he was married and that may have been a key part of what attracted her to him. She is after all, as Yujiro’s mentor said, a woman and experiences romantic desire even if the mentor is wrong to say that Kiwa sublimates her loneliness through art when in reality the reverse is true. After meeting Takemura even Yujiro remarks that she seems more like a woman, implying that her industry and forthrightness lend her a masculine quality as does her determination to get on in business. She first strikes up a business relationship with the sleazy Omiya (Eitaro Ozawa) whose wife is always watching him like a hawk though she manages to rebuff his attentions while establishing herself as business woman and in demand kimono designer. In pursuit of Takemura she is the one bringing him gifts and inviting him out for walks while Takemura remains somewhat conflicted and pulled along her wake.

Yet for all that, none of her family members really question the fact that she’s been carrying on with a married man and rather seem slightly relieved that she’s discovered an interest in romance or perhaps just anything outside of kimono dyeing. Even Takemura’s daughter suspects they’re romantically involved and doesn’t seem to mind. Yujiro remarks on Kiwa suddenly using the colour red which she never previously liked and it does seem to echo her reawakening passion. Takemura is also researching red fruit flies, which is less romantic, but also hints his barely suppressed longing. The film seems to align him with yellow flowers and Kiwa with pink. When they’re caught in a rainstorm and refuge in an inn owned by Kiwa’s childhood friend, the entire room in bathed in the glow of the Daimonji fire festival as their passions finally, and perhaps unwisely, overtake them as Takemura announces he’s thinking of moving far away perhaps to avoid this forbidden romance or otherwise for the health of his ailing wife who has been a Kyoto hospital for the last two years.

It’s finding out about Mrs Takemura’s likely terminal illness that seems to implode Kiwa’s romantic fantasy. After they’d made love for the first time, she had told Takemura that if she became pregnant she’d raise the child alone without intruding on his family life, which is to say she wasn’t really envisaging one with him. Her horror is on one level framed as guilt, that she now sees she’s committed an act of betrayal and resents Takemura when he tells her “it won’t be much longer” as if he were counting down the days until his wife passed away. Or worse, that he or others suspected that Kiwa willed her dead. But in reality the reverse is true. Mrs Takemura’s death is an existential threat to Kiwa’s independence. She doesn’t want to get married, even if loves Takemura, because if she did she wouldn’t be able to maintain her independence or career as a kimono dyer. She really does mean it when she says that likes it best when it’s just she and her father in their “cramped” old-fashioned dyeing shop without even an apprentice.

A tortured art student who seems to pine for her tells her as much, disappointed in her for her relationship with Takemura not out of moral censure but because he fears she’s betraying her art. Okamoto is much younger than her and she’s not interested in him romantically even if he’s painting slightly lewd interpretations of his mental image of her. At one point he appears with a bandage around his neck that implies he may have tried to take his own life and eventually announces he’s leaving Kyoto because he can’t secure his identity there. Ironically he’s happy that Kiwa and Takemura are now free to love each other when the opposite is now true. Now that he’s no longer a married man, Kiwa can no longer love him and is denied the possibility of having both romantic and artistic fulfilment. She is perhaps free in another way, backed by a deep red cloth hanging up to dry as she watches the May Day parade pass by with all of its waving red flags having embarked on a life that is defiantly of her choosing and fulfilled by the passion of art.

Trailer (no subtitles)

War, in Japanese cinema, had been largely relegated to the samurai era until militarism took hold and the nation embarked on wide scale warfare mixed with European-style empire building in the mid-1930s. Tomotaka Tasaka’s Five Scouts (五人の斥候兵, Gonin no Sekkohei) is often thought to be the first true Japanese war film, shot on location in Manchuria and trying to put a patriotic spin on its not entirely inspiring central narrative. Like many directors of the era, Tasaka is effectively directing a propaganda film but he neatly sidesteps bold declarations of the glory of war for a less controversial praise of the nobility of the Japanese soldier who longs to die bravely for the Emperor and lives only to defend his friends.

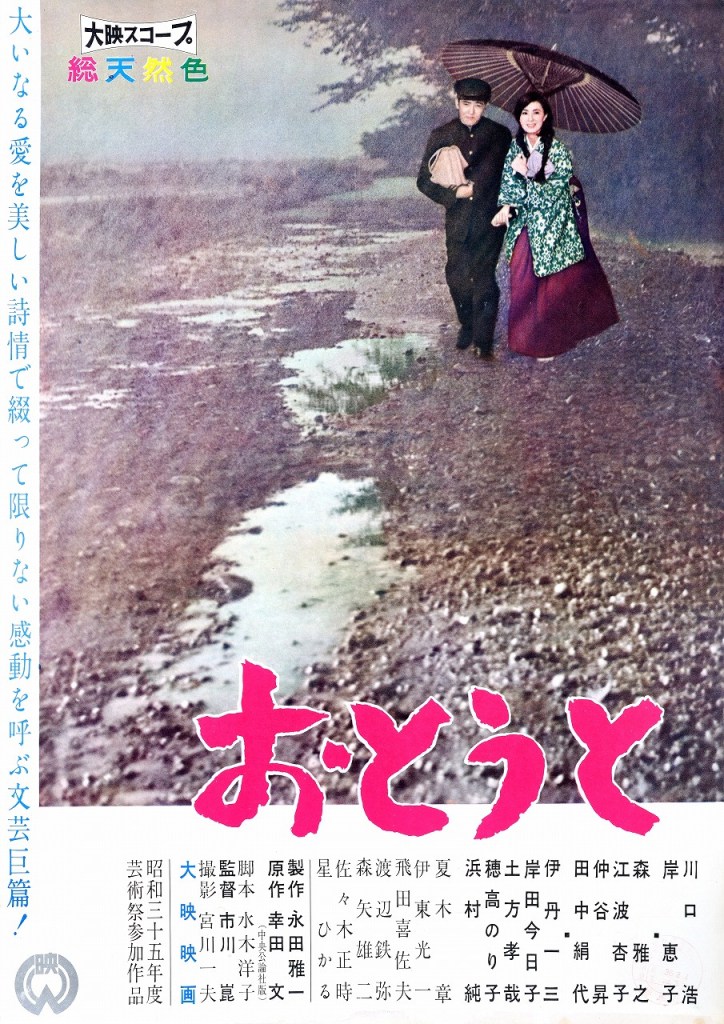

War, in Japanese cinema, had been largely relegated to the samurai era until militarism took hold and the nation embarked on wide scale warfare mixed with European-style empire building in the mid-1930s. Tomotaka Tasaka’s Five Scouts (五人の斥候兵, Gonin no Sekkohei) is often thought to be the first true Japanese war film, shot on location in Manchuria and trying to put a patriotic spin on its not entirely inspiring central narrative. Like many directors of the era, Tasaka is effectively directing a propaganda film but he neatly sidesteps bold declarations of the glory of war for a less controversial praise of the nobility of the Japanese soldier who longs to die bravely for the Emperor and lives only to defend his friends.  Perhaps oddly for a director of his generation, Kon Ichikawa is not particularly known for family drama yet his 1960 effort, Her Brother (おとうと, Ototo), draws strongly on this genre albeit with Ichikawa’s trademark irony. A Taisho era tale based on an autobiographically inspired novel by Aya Koda, Her Brother is the story of a sister’s unconditional love but also of a woman who is, in some ways, forced to sacrifice herself for her family precisely because of their ongoing emotional neglect.

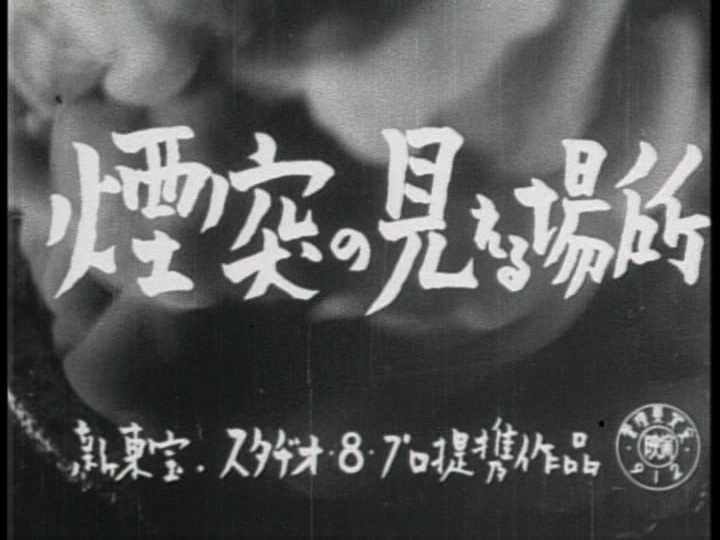

Perhaps oddly for a director of his generation, Kon Ichikawa is not particularly known for family drama yet his 1960 effort, Her Brother (おとうと, Ototo), draws strongly on this genre albeit with Ichikawa’s trademark irony. A Taisho era tale based on an autobiographically inspired novel by Aya Koda, Her Brother is the story of a sister’s unconditional love but also of a woman who is, in some ways, forced to sacrifice herself for her family precisely because of their ongoing emotional neglect. Where Chimneys are Seen (煙突の見える場所, Entotsu no Mieru Basho) is widely regarded as on of the most important films of the immediate post-war era, yet it remains little seen outside of Japan and very little of the work of its director, Heinosuke Gosho, has ever been released in English speaking territories. Like much of Gosho’s filmography, Where Chimneys are Seen devotes itself to exploring the everyday lives of ordinary people, in this case a married couple and their two upstairs lodgers each trying to survive in precarious economic circumstances whilst also coming to terms with the traumatic recent past.

Where Chimneys are Seen (煙突の見える場所, Entotsu no Mieru Basho) is widely regarded as on of the most important films of the immediate post-war era, yet it remains little seen outside of Japan and very little of the work of its director, Heinosuke Gosho, has ever been released in English speaking territories. Like much of Gosho’s filmography, Where Chimneys are Seen devotes itself to exploring the everyday lives of ordinary people, in this case a married couple and their two upstairs lodgers each trying to survive in precarious economic circumstances whilst also coming to terms with the traumatic recent past.