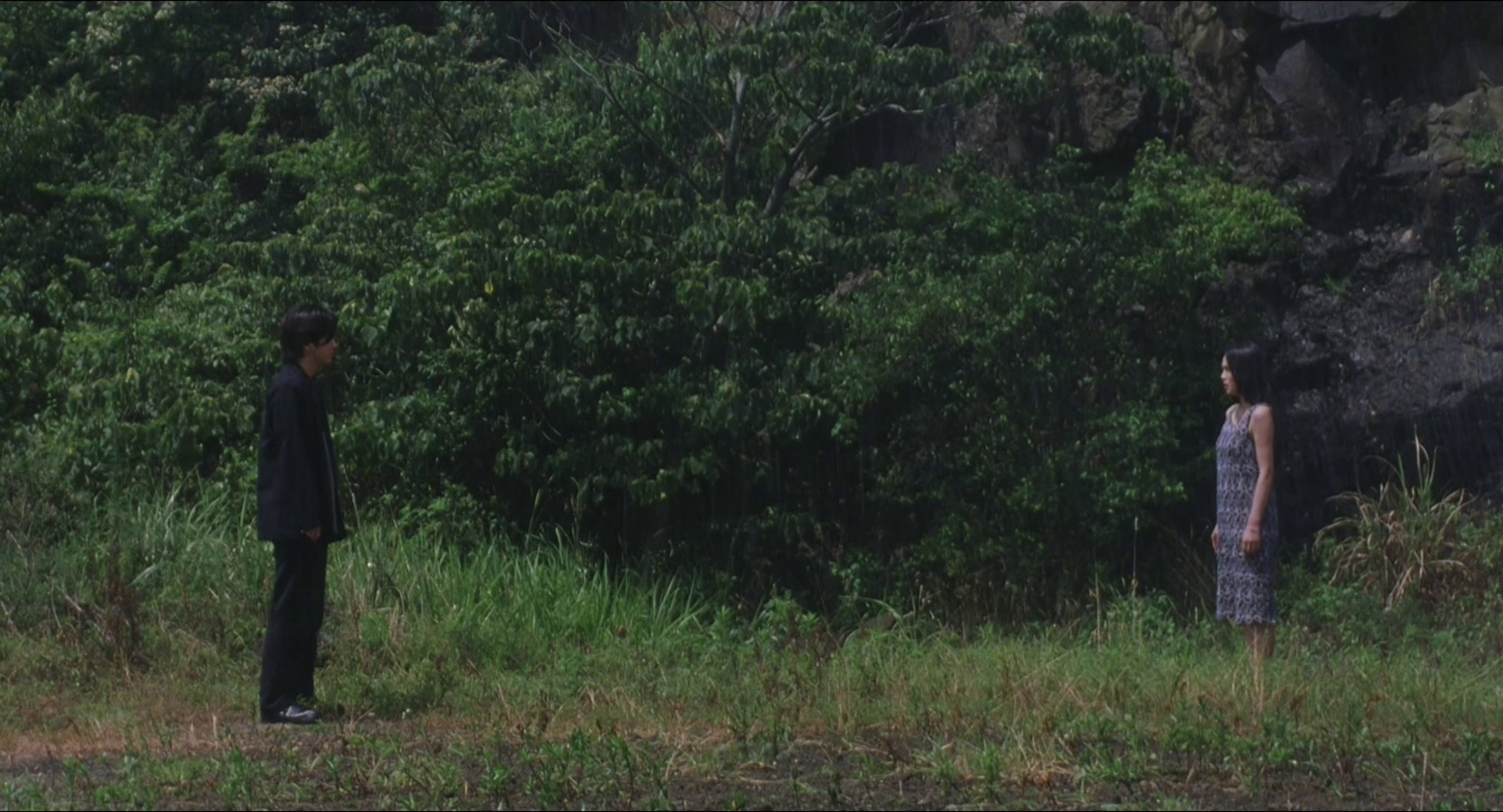

A down-on-his-luck handyman finds himself swept into intrigue when he agrees to a help a pretty young woman fake a kidnapping in Hideo Nakata’s noirish drama Chaos (カオス). Chaos is certainly what unfolds in the non-linear narrative as we try to piece together this fracturing tale of multiple betrayals and double crossings in which nothing and no one is quite as it seems and we can never really be sure just what game anyone is playing.

Goro (Masato Hagiwara), for instance, seems to be a bit of a sap. His ex-wife accuses him of being incapable of thinking of others, though his young son Noboru comes to him after having been bullied at school. He doesn’t seem to be very invested in his life of odd jobs which includes requests from lonely old men to play go as well as to visit the apartments of pretty women who’ve encountered some kind of plumbing disaster. Perhaps it’s no surprise he’s convinced to help Saori (Miki Nakatani) stage a kidnapping to test her husband’s affections seeing as she suspects he’s started an affair with a younger woman who is just nicer than she is, so she can’t compete.

What is surprising is that Goro turns out to be some sort of kidnapping expert. He explains to Saori that she should wear rope bindings for added authenticity when she’s released as well as refrain some taking showers. She should also not feed the tropical fish her friend asked her to, because if she’s been kidnapped then she’s not available, but then the fish will die, which means she’s sacrificing the life of living creatures just to prove a point. Though Goro treats her with tenderness, he frighteningly turns on after he’s helped her tie herself up, threatening rape. This is then revealed to be a ruse in order to get a real reaction of fear and terror for when he rings her husband Komiyama (Ken Mitsuishi) with the ransom request.

This reversal makes clear to us that we don’t know who we’re dealing and anyone could suddenly change at a moment’s notice. We’ve just been told, for instance, that Saori tied the ropes so she could easily untie them by herself to go to the bathroom, which means that she could have done so anytime while she thought Goro was attacking her but didn’t. Obviously, she may have been too frightened to think of it, but then again perhaps she is also playing along with her own game too. When Goro extorts Koniyama’s sister, it looks like a cunning double bluff to lend authenticity to the original kidnapping plot while simultaneously pulling off a different scam, but maybe it’s also Goro going rogue and doubling his pay packet.

Despite his circumstances, however, Goro doesn’t seem to be in this for the money so much as white knighting for Saori even though he obviously knows she’s already married. On realising she may have betrayed him, Goro goes into a fairly convincing detective mode, posing as a policeman in order to investigate. He discovers that Komiyama’s mistress was a model who’d recently been cast aside by the agency because of a rumour she slept with a client while they also seem to have a repressive rule about dating. One of her colleagues says she hardly ever goes home to the flat her agency rents for her because she’s secretly living with a boyfriend. This is, perhaps, a world in which a woman can’t really be all of who she is because men are always trying to imprint their vision of idealised femininity on them. Womanhood is, after all, a kind of performance and one which Saori may be manipulating for her own ends.

Yet it’s not clear where, if anywhere, the performances end and the authentic begins. Even having discovered at least a degree of the truth, Goro isn’t sure he can really trust Saori, while she may not really know either. What he resolves is that that might not matter, but what each of them is really looking for is a kind of escape from the constraints of their lives either through love or money only to discover that there is none, or else it lies only in death either literal or figural in a total reinvention of one’s persona. With shades of Vertigo, Nakata piles on the confusion and uncertainty to create an atmosphere of pure dread in which nothing, really, is quite as it’s assumed to be.

Trailer (English subtitles)