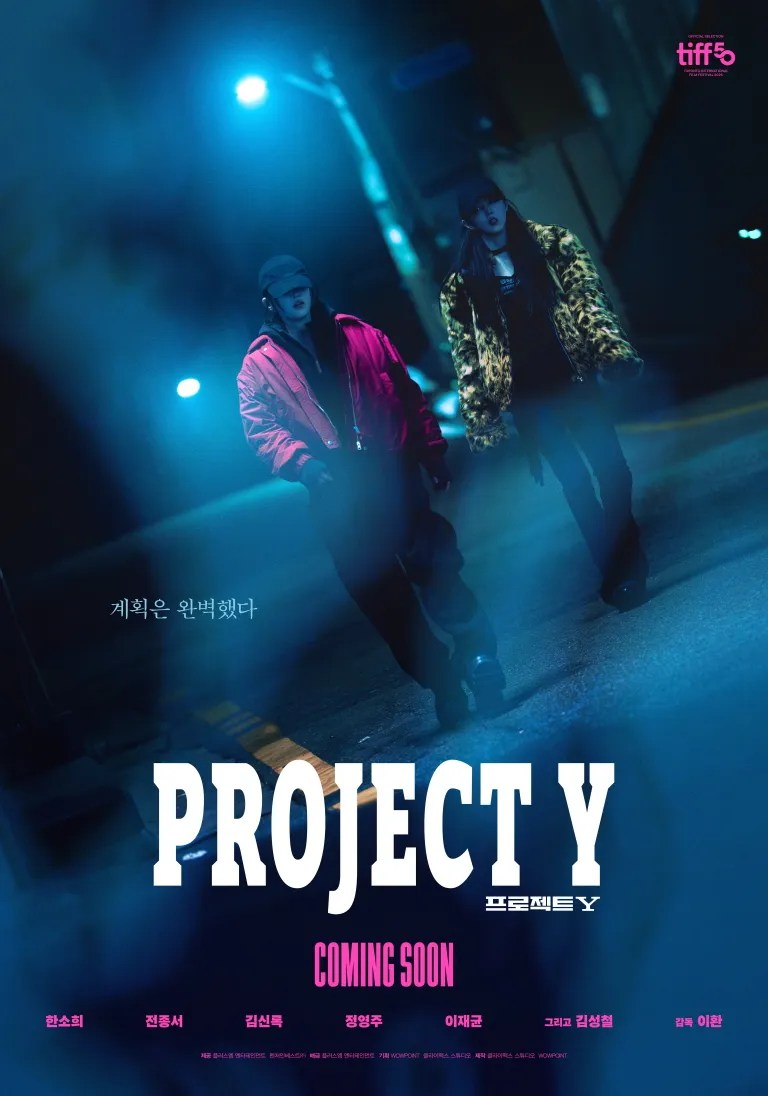

The opening sequence of Lee Hwan’s Project Y (프로젝트 Y) seems to echo the iconic intro of Millennium Mambo as two women look back over their shoulders as they traverse a seemingly endless tunnel. Later we realise that the tunnel is their passage out of the underworld of the red light district towards escape and liberation, not only from patriarchal control and their impossible lives, but from a generational legacy of abuse and entrapment.

Indeed, Ga-young (Kim Shin-rok) the adoptive mother of Mi-sun (Han So-hee) and birth mother of Do-kyung (Jeon Jong-seo), is fond of asking who is saving who when we’re all the same, and insisting that your life is yours to save. It’s a message the girls have taken to heart, yet they remain devoted to each other in a relationship that also appears to be romantic or perhaps has already transcended romance in the depth of their connection. Mi-sun has been working as a karaoke bar hostess for a number of years while Do-kyung works as her driver and occasional courier for various shady types. They plan to leave the red light district now Mi-sun has saved enough money to buy a florist’s from its retiring owner along with a downpayment on a apartment, but it turns out half the girls in the red light district have been scammed by a dodgy estate agent at the behest of local kingpin Blackjack (Kim Sung-cheol).

It seems that Blackjack may have done this deliberately in a nefarious plot to increase the girls’ debts and prevent them from leaving. Blackjack’s callousness is signalled early on when he tells the girls’ manager to get rid of a drooping plant if she can’t manage it and space the others out to disguise the gap. But on the flip side, Blackjack has a young and very silly wife who has got into host clubs and has been spending all his money on a young man who is openly exploiting her. Though the men are ostensibly in the same position as the women, they still have a greater power in preying on female loneliness while the women, by contrast, may be indulging in this behaviour precisely because it gives them an illusion of control they ordinarily don’t have a patriarchal society. Blackjack’s wife throws expensive gifts at her favourite host in an attempt to persuade him to enter a deeper relationship while blabbing her husband’s secrets. The host doesn’t seem to have realised it might be a bad idea to be messing around with Blackjack’s wife, while stealing his secret stash is going to annoy him even more and Blackjack’s not the sort of man you want to be annoyed with you.

Blackjack watches a video of a dog drowning in a tarpit while he works out, and this particular tarpit acts as a kind of vortex drawing all the greed in the red-light district towards it. Hearing about the plot to rob Blackjack, the girls decide to rob him first and blame it on a local hoodlum. But after retrieving a bag with the exact amount they lost, discover a stash of gold bars. It’s taking them too that damages the integrity of their quest and sets them on a course towards a direct confrontation with Blackjack as they try their hardest to escape the red light district for good.

The implication seems to be that if they take the money, they’ll never really be free because it stemmed from the source of their exploitation. This might in a way be what Ga-young is trying to teach the girls in her otherwise hard to read behaviour, sacrificing herself to save them from their poor decision to cross Blackjack while trying to catapult them free of the red-light district though she knows she herself can never leave. Slick and stylish, Lee’s noir stays just on the right side of realism despite its recurrent grimness and larger than life characters such as the Blackjack’s icy female enforcer Bull and captures both girls’ desire for a “normal life” of working in the day and sleeping at night, along with the cheerful solidarity of the hostesses as they band together to take revenge on Blackjack and finally free themselves from this world of constant betrayal and exploitation.

Project Y screened as part of this year’s LEAFF.

International trailer (English subtitles)