The Korea of the early ‘80s was not an altogether happy place. One dictator fell in 1979, but hopes of returning to democracy were dashed when general Chun Doo-hwan staged a coup and instigated martial law, brutally suppressing a large scale democracy protest in Gwangju in 1980 (though the news of the incident was also suppressed at the time it took place). People in the Slums (꼬방동네 사람들, Kkobangdongne Salamdeul), adapted from the best selling novel by Lee Dong-cheol, is not an overtly political film but takes as its heroes those who have lost out in the nation’s bold forward march into the capitalist future. Opening with a voice over from the author himself, the film dedicates itself to “the memory of neighbours of bygone days”, remembering both the hardships but also the fierce sense of community and warmth to be found among those living at the bottom of the heap.

The Korea of the early ‘80s was not an altogether happy place. One dictator fell in 1979, but hopes of returning to democracy were dashed when general Chun Doo-hwan staged a coup and instigated martial law, brutally suppressing a large scale democracy protest in Gwangju in 1980 (though the news of the incident was also suppressed at the time it took place). People in the Slums (꼬방동네 사람들, Kkobangdongne Salamdeul), adapted from the best selling novel by Lee Dong-cheol, is not an overtly political film but takes as its heroes those who have lost out in the nation’s bold forward march into the capitalist future. Opening with a voice over from the author himself, the film dedicates itself to “the memory of neighbours of bygone days”, remembering both the hardships but also the fierce sense of community and warmth to be found among those living at the bottom of the heap.

Myeong-suk (Kim Bo-yeon), a still young-ish woman with a young son, lives in a slum outside of the city with her second husband, Tae-sub (kim Hee-ra). Nicknamed “Black Glove” because of the glove she always wears on her right hand, Myeong-suk is about to open her own business – a small grocery store serving the local residents, but her happiness is tempered with anxiety. Tae-sub, despite his promises, steals money from Myeong-suk to go drinking and gambling, is occasionally violent, and does not get on with her son, Jun-il, who refers to him as Mr. Piggy. Jun-il is also a constant worry because he’s picked up a habit of stealing things and generally causing trouble around the neighbourhood. When Myeong-suk’s former husband and the father of Jun-il, Ju-seok (Ahn Sung-ki), catches sight of her by chance one day, the past threatens to eclipse the small hope of her future.

Life in the slums is not easy. There are few resources, few people are working and there are lots of children with no money to feed and clothe them. Fights are frequent but often unserious. The community pull together to support each other, turning out in force for the grand opening of Myeong-suk’s shop or the 60th birthday celebration of a fellow resident. Besides Myeong-suk, her second husband, and son, the slum is home to a collection of unusual characters from a widow who dresses in white and does strange dances to entertain the locals, to the pastor who does his best to help where he can. A poor drunken woman makes a fool of herself all over town, nursing a crush on the pastor but seemingly unable to move past her dependency on alcohol and whatever it is that caused it and landed her in the slum.

Myeong-suk’s early life would not have suggested her current trajectory, as Bae reveals in Ju-seok’s flashbacks of his courtship to the woman who would become his wife. Ju-seok, a pickpocket, spotted Myeong-suk on a bus and it was love at first sight. Eventually he married her but never revealed his illicit occupation until he was finally arrested. For the sake of his wife and child, Ju-seok attempts to go straight but his efforts are frustrated by bad luck, temptation, and unforgiving policemen. No matter how hard Ju-seok tries to be a decent, hardworking, family man, the economic instability of late ‘70s Korea will not allow him to do it.

Myeong-suk waits for him, but there comes a point she cannot wait anymore. Her second husband is no better than her first and, just like Ju-seok, is hiding something from her. Tae-sub is a bully and a bruiser who is only using Myeong-suk as a convenient place to hide. She cannot rely on him for affection, protection, or financial stability. Ju-seok, at least, did love Myeong-suk even if that love was the very thing which kept leading him back into a life of crime which then took him away from her. Once again love is a luxury the poor cannot afford .

Where the general atmosphere may seem destined for a tragedy for the resilient, suffering Myeong-suk, her damaged son, and reformed taxi-driver former husband, Bae gives them hope for a warmer, if not a better, future. As Myeong-suk prepares to leave the slum, the pastor, encircled by the residents, reads out a passage reminding the locals that a neighbour’s suffering is one’s own suffering while the drunken woman who previously hated children appears to have sobered up and happily hugs a child. Myeong-suk makes a selfless gesture of atonement and solidarity in giving the money from selling her shop to another single mother whose youngest three all have different fathers, perhaps indicating the difficulty of her life since the father of her eldest passed away. Tae-sub too reforms, decides to face the past he’s been running from and make amends for his former life, facilitating a possible reunion for the star-crossed lovers Myeong-suk and Ju-seok. The future suddenly looks brighter, but it remains uncertain and who knows if love and a taxi-driver’s salary will be enough to keep Ju-seok on the straight and narrow as a responsible husband and father in turbulent ‘80s Korea.

People in the Slum screens as part of the London Korean Film Festival 2017 which is hosting a mini Bae Chang-ho retrospective of three films at each of which the director will be present for a Q&A.

The film was also recently released on all regions blu-ray courtesy of the Korean Film Archive. In addition to English subtitles on the main feature, the blu-ray also includes English subtitles for the commentary track by Bae Chang-ho and film critic Kim Sungwook, and comes with a bilingual booklet featuring essays by Jang Byung-won (programmer for Jeonju International Film Festival), Lee Yong-cheol (film critic), and Chris Berry (King’s College London).

You can also watch the entirety of the film legally and for free courtesy of the Korean Film Archive’s YouTube Channel.

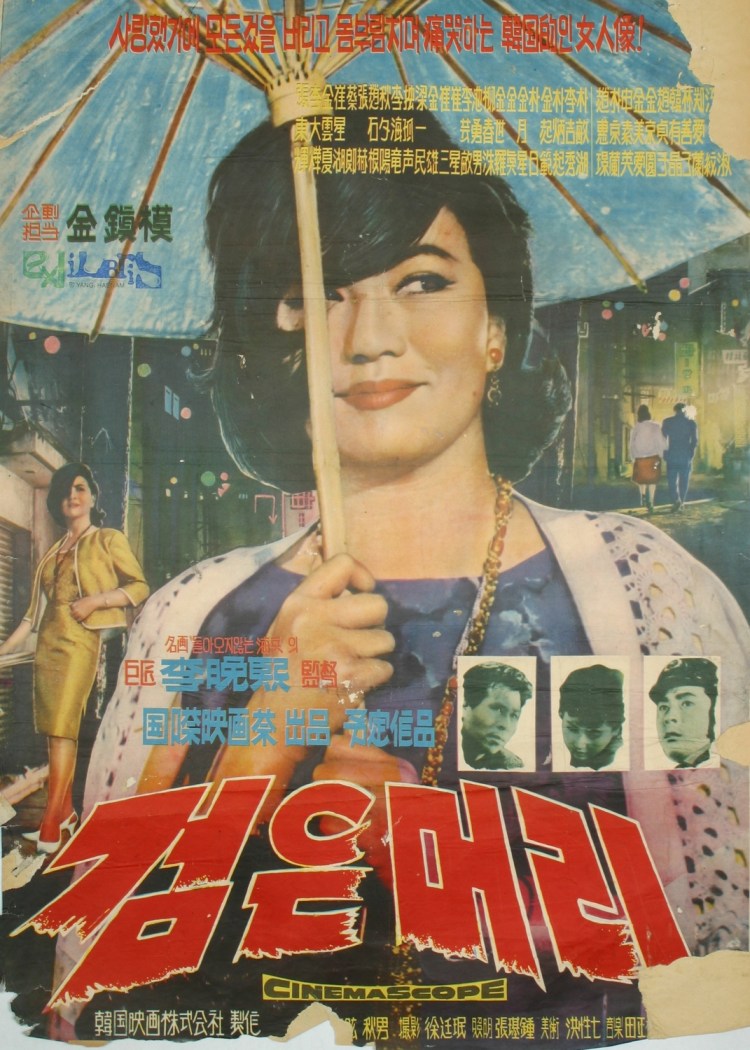

It’s Not Her Sin (그 여자의 죄가 아니다, Geu yeoja-ui joega anida) is, in contrast to its title, nowhere near as dark or salacious as the harsher end of female melodramas coming out of Hollywood in the 1950s. It’s not exactly clear to which of the central heroines the title refers, nor is it clear which “sin” it seeks to deny, but neither of the two women in question are “bad” even if they have each transgressed in some way. Drawing inspiration from the murkiness of a film noir world, Shin Sang-ok adapts the popular novel by Austrian author Gina Kaus by way of a previous French adaptation, Conflit. Shin sets his tale in contemporary Korea, caught in a moment of transition as the nation, still rebuilding after a prolonged period of war and instability, prepares to move onto the global stage while social attitudes are also in shift, but only up to a point.

It’s Not Her Sin (그 여자의 죄가 아니다, Geu yeoja-ui joega anida) is, in contrast to its title, nowhere near as dark or salacious as the harsher end of female melodramas coming out of Hollywood in the 1950s. It’s not exactly clear to which of the central heroines the title refers, nor is it clear which “sin” it seeks to deny, but neither of the two women in question are “bad” even if they have each transgressed in some way. Drawing inspiration from the murkiness of a film noir world, Shin Sang-ok adapts the popular novel by Austrian author Gina Kaus by way of a previous French adaptation, Conflit. Shin sets his tale in contemporary Korea, caught in a moment of transition as the nation, still rebuilding after a prolonged period of war and instability, prepares to move onto the global stage while social attitudes are also in shift, but only up to a point.

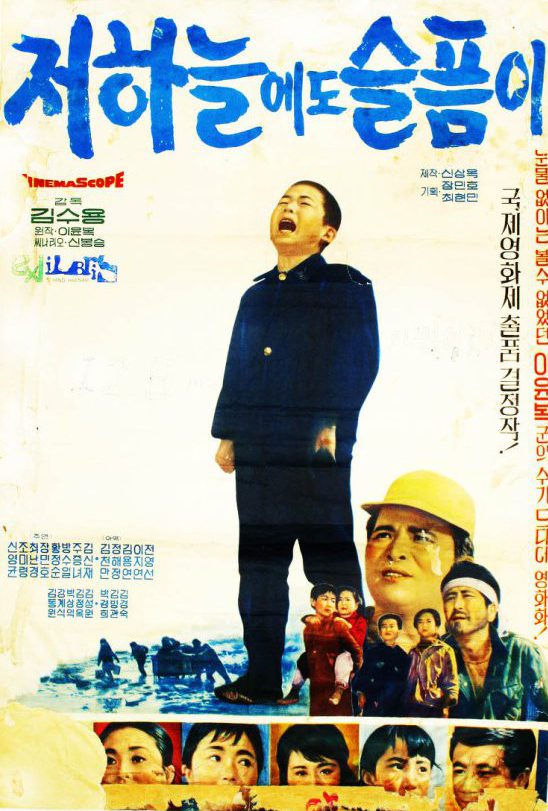

It’s a sorry enough tale to hear that many silent classics no longer exist, regarded only as disposable entertainment and only latterly collected into archives and preserved as valuable film history, but in the case of South Korea even mid and late 20th century films are unavailable thanks to the country’s turbulent political history. Though often listed among the greats of 1960s Korean cinema, Sorrow Even Up in Heaven (저 하늘에도 슬픔이, Jeo Haneuledo Seulpeumi) was presumed lost until a Mandarin subtitled print was discovered in an archive in Taiwan. Now given a full restoration by the Korean Film Archive, Kim’s tale of societal indifference to childhood poverty has finally been returned to its rightful place in cinema history but, as Kim’s own attempt to remake the film 20 years later bears out, how much has really changed?

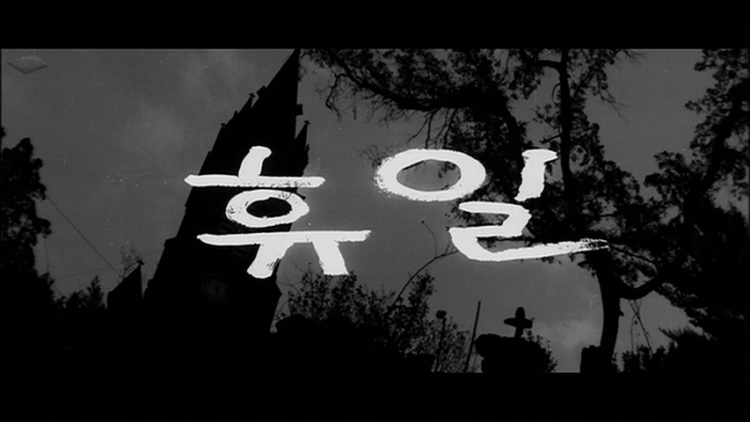

It’s a sorry enough tale to hear that many silent classics no longer exist, regarded only as disposable entertainment and only latterly collected into archives and preserved as valuable film history, but in the case of South Korea even mid and late 20th century films are unavailable thanks to the country’s turbulent political history. Though often listed among the greats of 1960s Korean cinema, Sorrow Even Up in Heaven (저 하늘에도 슬픔이, Jeo Haneuledo Seulpeumi) was presumed lost until a Mandarin subtitled print was discovered in an archive in Taiwan. Now given a full restoration by the Korean Film Archive, Kim’s tale of societal indifference to childhood poverty has finally been returned to its rightful place in cinema history but, as Kim’s own attempt to remake the film 20 years later bears out, how much has really changed? Post-war cinema took many forms. In Korea there was initial cause for celebration but, shortly after the end of the Japanese colonial era, Korea went back to war, with itself. While neighbouring countries and much of the world were engaged in rebuilding or reforming their societies, Korea found itself under the corrupt and authoritarian rule of Syngman Rhee who oversaw the traumatic conflict which is technically still ongoing if on an eternal hiatus. Yu Hyun-mok’s masterwork Aimless Bullet (오발탄, Obaltan) takes place eight years after the truce was signed, shortly after mass student demonstrations led to Rhee’s unseating which was followed by a short period of parliamentary democracy under Yun Posun ending with the military coup led by Park Chung-hee and a quarter century of military dictatorship. Of course, Yu could not know what would come but his vision is anything but hopeful. Aimless Bullets all, this is an entire nation left reeling with no signposts to guide the way and no possible destination to hope for. All there is here is tragedy, misery, and inevitable suffering with no possibility of respite.

Post-war cinema took many forms. In Korea there was initial cause for celebration but, shortly after the end of the Japanese colonial era, Korea went back to war, with itself. While neighbouring countries and much of the world were engaged in rebuilding or reforming their societies, Korea found itself under the corrupt and authoritarian rule of Syngman Rhee who oversaw the traumatic conflict which is technically still ongoing if on an eternal hiatus. Yu Hyun-mok’s masterwork Aimless Bullet (오발탄, Obaltan) takes place eight years after the truce was signed, shortly after mass student demonstrations led to Rhee’s unseating which was followed by a short period of parliamentary democracy under Yun Posun ending with the military coup led by Park Chung-hee and a quarter century of military dictatorship. Of course, Yu could not know what would come but his vision is anything but hopeful. Aimless Bullets all, this is an entire nation left reeling with no signposts to guide the way and no possible destination to hope for. All there is here is tragedy, misery, and inevitable suffering with no possibility of respite.

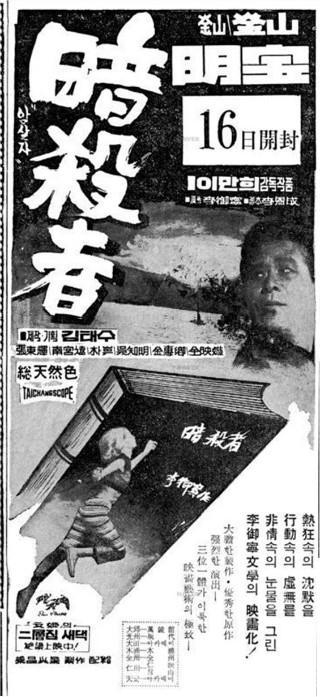

Lee Man-hee was one of the most prolific and high profile filmmakers of Korea’s golden age until his untimely death at the age of 43 in 1975. Like many directors of the era he had his fare share of struggles with the censorship regime enduring more than most when he was arrested for contravention of the code with his 1965 film Seven Female POWs and later decided to shelve an entire project in 1968’s

Lee Man-hee was one of the most prolific and high profile filmmakers of Korea’s golden age until his untimely death at the age of 43 in 1975. Like many directors of the era he had his fare share of struggles with the censorship regime enduring more than most when he was arrested for contravention of the code with his 1965 film Seven Female POWs and later decided to shelve an entire project in 1968’s  Long thought lost, Tuition (수업료, Su-eop-ryo) is an unusual example of Korean film made during the Japanese colonial period. Released in 1940, the film depicts the lives of ordinary people facing hardship during difficult economic conditions though there is no reference made to the ongoing military situation. The story itself is inspired by a prize winning effort by a real life school boy who was doubtless experiencing something similar to the trials of Yeong-dal, however, directors Choi In-gyu and Bang Han-joon made several subversive changes to the script at the filming stage in an attempt to get around the censorship regulations.

Long thought lost, Tuition (수업료, Su-eop-ryo) is an unusual example of Korean film made during the Japanese colonial period. Released in 1940, the film depicts the lives of ordinary people facing hardship during difficult economic conditions though there is no reference made to the ongoing military situation. The story itself is inspired by a prize winning effort by a real life school boy who was doubtless experiencing something similar to the trials of Yeong-dal, however, directors Choi In-gyu and Bang Han-joon made several subversive changes to the script at the filming stage in an attempt to get around the censorship regulations.