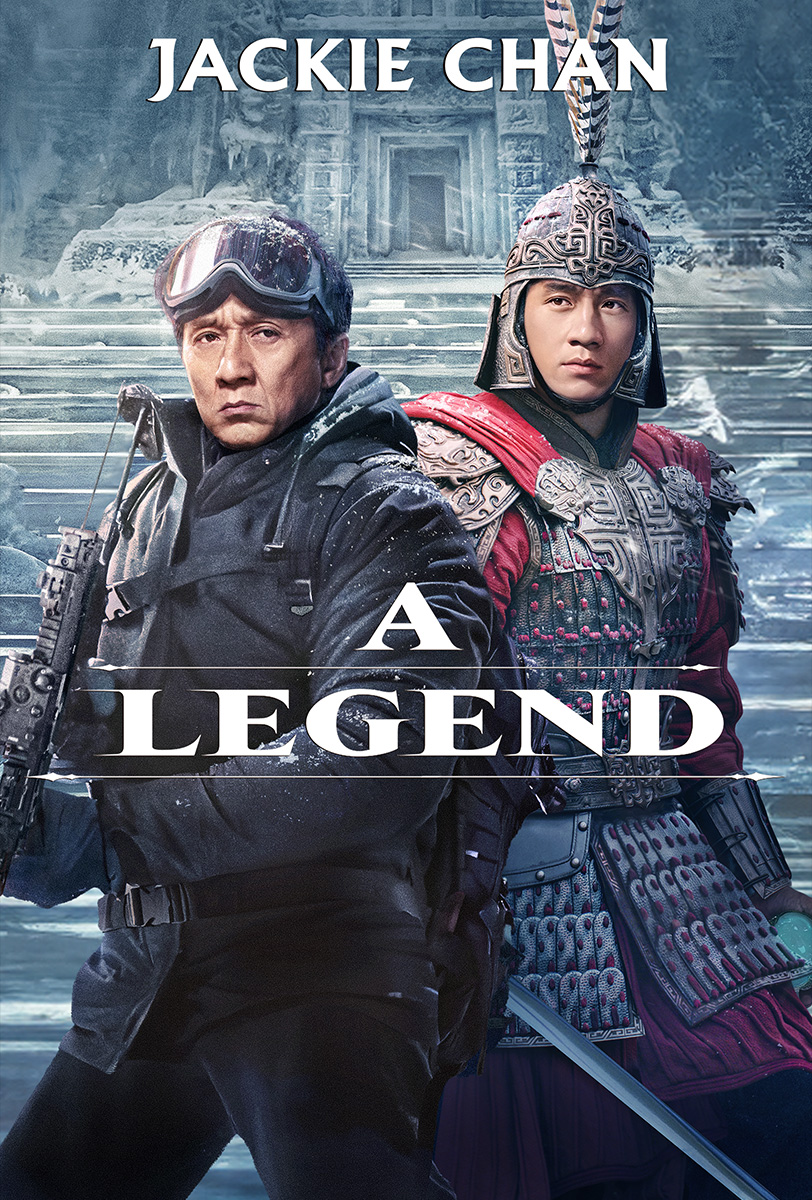

The funny thing about the strangely generic title of Stanley Tong’s latest Jackie Chan vehicle A Legend (传说, chuánshuō) is that it’s at least partly in reference to its now ageing star rather than the tragic love story at the film’s centre which at least tries to echo the epic romances of historical fiction. That might in part explain the rather dubious decision to use AI de-aging technology to cast Chan as the tragic lover in addition to his role as a veteran archeologist researching the gravesite of a Han general’s horse.

While de-aging Chan robs an age-appropriate actor of the opportunity, it’s equally true that it adds another note of uncanniness to the historical scenes contributing to their rather lifeless quality and otherwise becoming a frustrating distraction given that more often than not the actor’s face simply appears odd and doesn’t particularly look like a young Chan anyway any more than casting a younger actor with a physical resemblance might have done. In any case, despite the frequent discussions of history among Chan’s team, the historical scenes have a fantastical quality that’s much more like contemporary video games than classic wuxia. This may be deliberate given that a new addition to Professor Fang’s team is a video game developer who wants to create a game set in this era and is keen to get Fang on board as a consultant, though the aesthetic mostly detracts from the setting in the jarring use of CGI. Heroine Mengyun (Gülnezer Bextiyar) performs what is intended to be an impressive Hun sword dance, but as the sword is CGI it has no sense of skill or danger. It aligns clumsily with her physical movements like that in a video game cutscene and has a disturbingly weightless quality. The same phenomenon also mars the film’s action scenes which sometimes have an odd quality as if CGI has also been used to impose an actor’s face on that of a stunt double or somehow alter their movements.

Aside from that, there is some nice cinematography that captures the majesty of the Chinese landscape though even this is sometimes drowned out by the syrupy score which is again quite reminiscent of a video game. Supposedly a spiritual sequel to The Myth and Kung Fu Yoga, the central conceit of the film is that through a jade pendant found in the grave, Fang and his assistants become part of a collective dream which is a flashback to the distant past while it later transpires that they’re being manipulated by a malevolent force in the present who wants to rob China of its historical treasures by finding a secret sanctuary built by the Huns to store the gold statues they stole from the Hans to use as objects of worship. Accordingly, there’s some pointed commentary about how it’s illegal to steal or traffic historical artefacts which should be protected as symbols of China’s essential culture. It’s no coincidence that the villains have Western accents and begin speaking to each other in English as they wilfully blow up a newly discovered historical site.

The modern scenes do, however, have an awkward kind of comedy going on in the form of in jokes between Fang’s team such as the non-love story between assistants Xinran (Xiao Ran Peng) and the clueless Wang Jing (Lay Zhang Yixing) who completely misses all of her hints and seems to be unaware of the subtext of phrases such as “come in for coffee” or that “incredibly expensive bracelet would really suit me.” Chan also gets rescued from drowning by a family inexplicably ice fishing in this really remote place who take quite a long time to realise he’s not some kind of weird talking fish. Though Chan does get his own action sequence at the film’s conclusion, it’s fairly incongruous for a professor of archeology to possess these kinds of skills which are otherwise out of keeping with the fatherly, professorial character Chan plays up to that point even if there is a distinct hint of Indiana Jones in the instance that all of this should be a museum. The little boy who found the pendant even gets a pat on the head for reporting it to the authorities rather than trying to sell it or keep it for himself. Nevertheless, it speaks of something that the digressions into historical legend are often more interesting than the retelling of the legend itself which never really takes flight despite the flying arrows and charging horses of world in which the heroes can only dream of the supposedly peaceful and harmonious society that exists far in the future.

A Legend is released in the US on Digital, blu-ray, and DVD 21st January courtesy of Well Go USA.

Trailer (English subtitles)

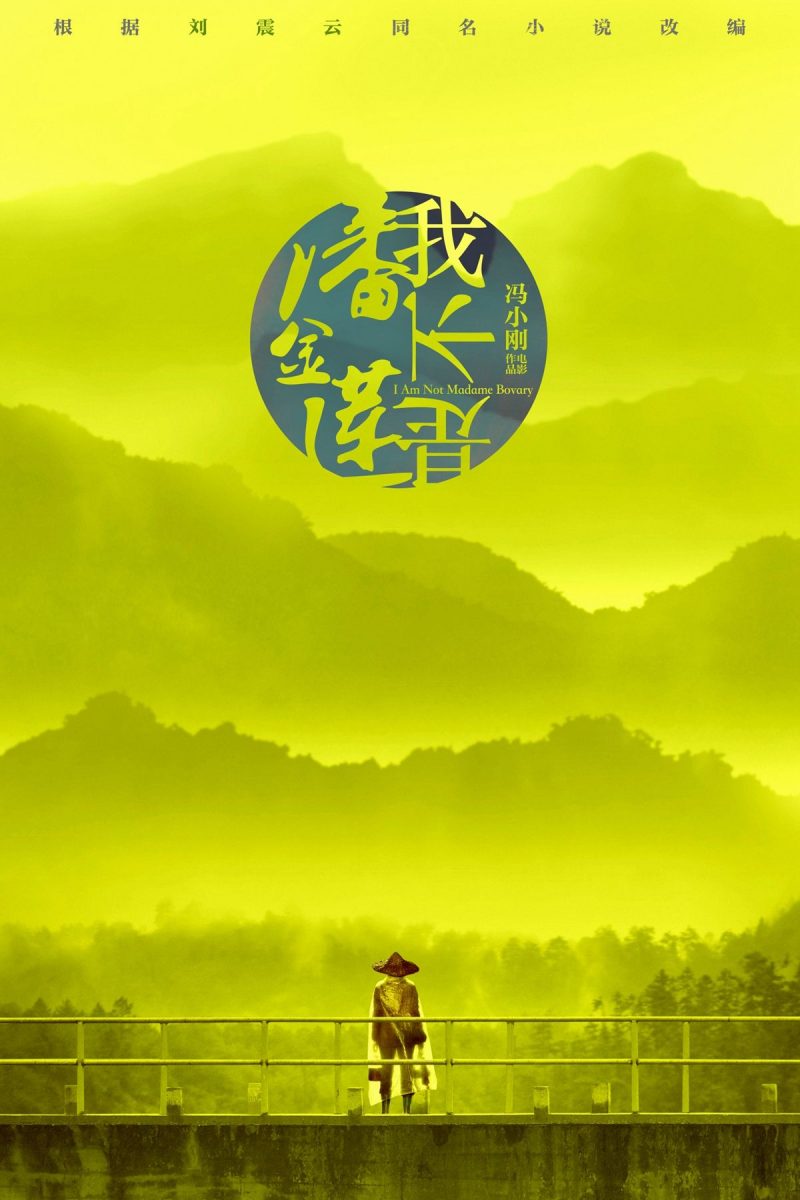

Feng Xiaogang, often likened to the “Chinese Spielberg”, has spent much of his career creating giant box office hits and crowd pleasing pop culture phenomenons from World Without Thieves to Cell Phone and You Are the One. Looking at his later career which includes such “patriotic” fare as Aftershock, Assembly, and

Feng Xiaogang, often likened to the “Chinese Spielberg”, has spent much of his career creating giant box office hits and crowd pleasing pop culture phenomenons from World Without Thieves to Cell Phone and You Are the One. Looking at his later career which includes such “patriotic” fare as Aftershock, Assembly, and