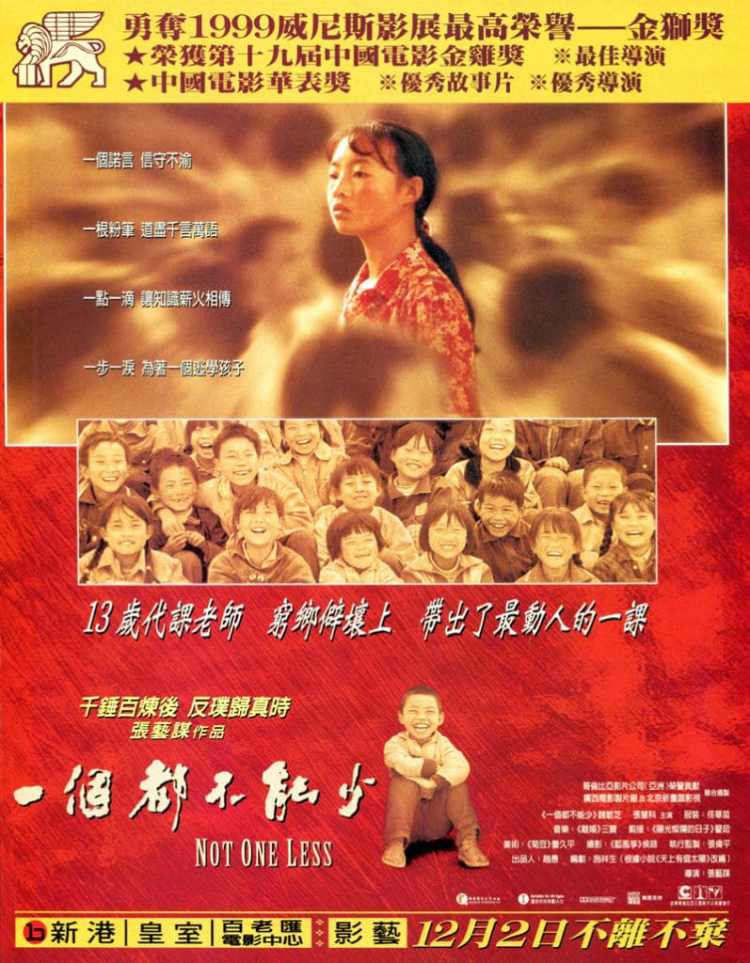

It’s tough being a kid in rural China. Childhood is perhaps the rarest of commodities, all too often cut short by the concerns of the adult world, but then again sometimes childish innocence can bring forth the real change in which grownups have long stopped believing. Zhang Yimou is no stranger to the struggles of life in China’s remote villages, but in Not One Less (一个都不能少, Yīgè Dōu Bùnéng Shǎo) he crouches a little closer to the ground as one tenacious little girl finds herself thrust into an unexpected position of authority and then cast away on an odyssey to rescue a lost sheep.

It’s tough being a kid in rural China. Childhood is perhaps the rarest of commodities, all too often cut short by the concerns of the adult world, but then again sometimes childish innocence can bring forth the real change in which grownups have long stopped believing. Zhang Yimou is no stranger to the struggles of life in China’s remote villages, but in Not One Less (一个都不能少, Yīgè Dōu Bùnéng Shǎo) he crouches a little closer to the ground as one tenacious little girl finds herself thrust into an unexpected position of authority and then cast away on an odyssey to rescue a lost sheep.

The girl, 13-year old Wei Minzhi has been brought over from an adjacent village to substitute for the local teacher whose mother is ill, meaning he needs to take a month off to go back to his own remote village and look after her. The problem is that no-one would agree to spend a month teaching little kids in a rural backwater for almost no money. Wei Minzhi graduated primary school which makes her one of the most educated people around and at least means that she’s a little way ahead of some of the other kids and, to be fair, teaching methods here generally end at copying the lessons from the master book up onto the blackboard so the kids can copy them down and study in their own time. Given the relative poverty of the village, children often drop out of school altogether because their parents need them at home. Teacher Gao has promised Wei 10 extra yuan if the same number of kids are still coming to school when he comes back as there were when he left.

Documenting daily life in the village, the early part of the film strikes a warm and comedic tone to undercut the hardship the villagers face. The Mayor, apparently a slightly dishonest but well meaning sort, is doing his best but the village is so poor that the children turn desks into beds and huddle together to sleep in the school. Chalk is strictly rationed and resources are scarce. Wei takes to her new found authority with schoolmarmish tenacity but struggles to exert her authority over her charges, and especially over one cheeky little boy, Zhang Huike.

When Zhang Huike disappears one day and Wei finds out he’s been sent to the city, she becomes fixated on the idea of going after him to drag him back and make sure she gets her 10 yuan bonus. The quest is a fallacious one – it will coast Wei far more than the 10 yuan bonus to get to the city and back so it’s hardly cost effective, but Wei is a literal sort and doesn’t tend to think things through. Nevertheless, the need to figure out how to get Zhang back does finally get her teaching as she gets the kids to help her do the calculations of how much money she’s going to need and to figure out how to get it.

If life in the village was tough, the city is tougher. When Wei arrives and tries to find Zhang, she winds up at the dorm of a construction site which is peopled exclusively by children who are (presumably) all working here to help their families out of poverty. Zhang, however, got lost on the way to his new job and is currently wandering the city alone, staring enviously at meat buns until someone takes pity on him and hands him one. Luckily he later meets a kind restaurant owner who takes him in off the street and gives him food in return for dishwashing. Wei, meanwhile, is completely at a loss as to how to look for Zhang. She hits on the idea of fliers but doesn’t think to leave contact details beyond the name of her school – after all, everyone in the village knows where the school is so why wouldn’t they in the city. Later someone recommends she try TV only for her to become semi-exploited for a human interest story on rural education in which the rabbit-in-the-headlights Wei can do little more than burst into tears and plead for Zhang’s return.

Wei’s single-mindedness may eventually reap rewards, but it’s impossible to escape the fact that it was motivated out of pure self interest. She wanted her 10 yuan bonus, and she never stopped to think about anyone’s else situation so long as she got it. Thus when scouts arrive from a nearby sports school with an amazing opportunity for one of her pupils, she tries to mess it up just so she’ll get the money. Similarly she’s determined to bring Zhang back even after visiting his home and meeting his bedridden mother who explains the family situation that necessitates sending her 11-year-old son away to work on a construction site. Despite having been warned about the chalk shortage, she allows half of it to get ground into the floor because she’s too busy trying to assert her authority to realise the (accidentally) destructive effects of her own actions. Nevertheless, her bullheadedness does eventually pay off. Asked about his experiences in the city, Zhang Huike remarks that the city is “beautiful and prosperous” before looking sad and admitting that he’ll never forget that he had to beg for food. Cities, it seems, are teeming hubs of wealth and success but they’re also cold, lonely, and so anonymous that small boys like Zhang get lost amid the hustle and bustle of the individualist life.

International trailer (English voice over)