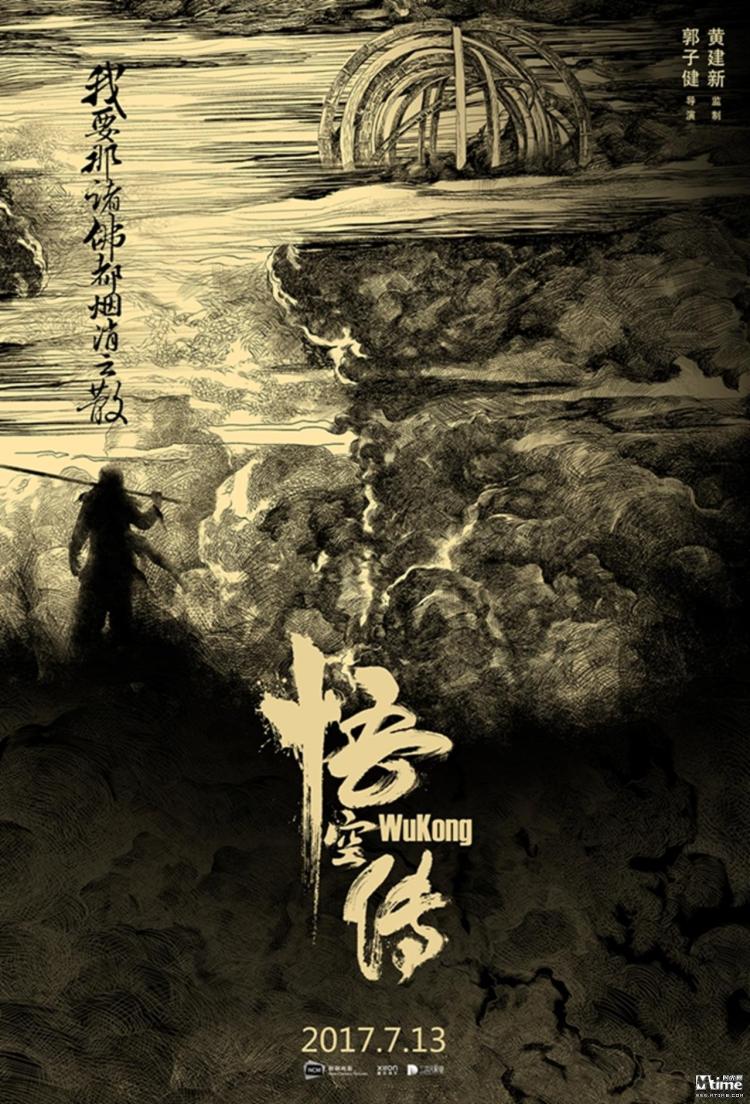

As it stands, contemporary Chinese cinema is veering dangerously close to Monkey King fatigue. Stephen Chow brought his particular sensibilities to the classic Journey to the West before Donnie Yen put on a monkey suit for Cheang Pou-soi, both of which were quickly followed by sequels. Eddie Peng is the latest to pick up the staff for Gallants’ Derek Kwok, though this is a much more youthful incarnation of the iconic hero, acting as a kind of prequel to recent incarnations and as a coming of age tale for the titular “demon” as recounted in the popular online novel Legend of Wukong by Jin Hezai. Told in grand style, Kwok’s Wu Kong (悟空传, Wù Kōng Zhuàn) is a star studded box office extravaganza but embraces both extremes of its family friendly, mainstream blockbuster thrills.

As it stands, contemporary Chinese cinema is veering dangerously close to Monkey King fatigue. Stephen Chow brought his particular sensibilities to the classic Journey to the West before Donnie Yen put on a monkey suit for Cheang Pou-soi, both of which were quickly followed by sequels. Eddie Peng is the latest to pick up the staff for Gallants’ Derek Kwok, though this is a much more youthful incarnation of the iconic hero, acting as a kind of prequel to recent incarnations and as a coming of age tale for the titular “demon” as recounted in the popular online novel Legend of Wukong by Jin Hezai. Told in grand style, Kwok’s Wu Kong (悟空传, Wù Kōng Zhuàn) is a star studded box office extravaganza but embraces both extremes of its family friendly, mainstream blockbuster thrills.

So, Sun Wu Kong (the Monkey King), as you know, was born from a stone atop Mount Huaguo – a remnant of a giant who attempted to battle the heavens but was defeated. Heaven fears the existence of the mischievous demon and determines to destroy him but he’s saved by a teacher who gives him a human form and the name Sun Wu Kong. Devastated by the destruction of his homeland, Wu Kong (Eddie Peng) vows revenge on the Heavens and travels to voice his concerns in person. Resenting his “destiny” Wu Kong focusses his attentions on destroying the divine astrolabe which ascribes fate to all beings, but little does he know that its guardian, Hua Ji (Faye Yu), wants his heart for herself so that she might rule all of Heaven and Earth.

Kwok opens with a beautifully designed sequence modelled after traditional chinese ink paintings in which he recounts the pre-history and birth of the demon later known as Sun Wu Kong. Unlike some other recent attempts to tackle this famously fantastical world, Wu Kong boasts fabulously high production values as well as much better special effects than most Chinese blockbusters, and it helps that Eddie Peng is not burdened with spending the majority of the movie in prosthetics.

Nevertheless for all the lack of actual plot, there is a lot going on and the brisk pace of the exposition filled opening is hard to follow (but, thankfully, details are unimportant). As in his other adventures, Wu Kong ends up with a collection of friends and enemies including love interest Azi (Ni Ni) – the equally rebellious daughter of Hua Ji who has just returned from 100 years in “re-education” exile and fiercely resents her mother’s cruel and controlling nature. Likewise her half brother, Erlang (Shawn Yue) has also arrived home at just the right/wrong moment and is conflicted in his views towards the Heavens – wanting to be accepted as a true “immortal” but also wanting to protect his little sister, so obviously unhappy with the ruling regime. Two more cohorts appear in the gadget laden Juan Lian (Qiao Shan) – a kind hearted man with a hopeless crush on Azi, and the lovelorn retainer, Tian Peng (Oho Ou), still pining after his childhood sweetheart who was exiled to the mortal world.

Much of the central drama occurs after Wu Kong, Erlang, and Tian Peng destroy “The Bridge of Destiny” and are cast down to the mortal world themselves along with Juan Lian and Azi. Finding themselves in a desperate village which happens to be on the former site of Mount Huaguo, the five start to believe they’ll never be going home and discuss staying to help the villagers defeat the “Cloud Demon” which has been stealing all their water. Interacting with the villagers teachers each of them some vaiuable lessons, but “destiny” is still waiting, and trying to change the fate of these desperate people may have disastrous, unforeseen consequences.

Once again, Wu Kong’s battle lies in the Heavens and may end up costing more than it gains. Kwok’s direction is conventional in one sense, but also manages to add a youthful energy which befits the film’s message. Wu Kong’s rebellion is the same as many a young a man’s – against a pre-ordained fate. As he puts it in the punkish final title cards, he will not be blinded by the sky or bound by the Earth – he will decide his own destiny and will never submit himself to the authority of any god or Earthly power. Attempts at melodrama largely fall flat, as does the unwise decision to shift to fantasy sequences for moments of high emotion, not to mention the inclusion of a sappy pop song to really ram home the theme of tragic romance, but whatever Wu Kong’s failings it succeeds brilliantly in its primary objective as an admittedly vacuous summer blockbuster primed to speak to the hearts of hemmed in teens everywhere.

Currently on UK release at selected cinemas.

Original trailer (Mandarin with English/simplified Chinese subtitles)

Taiwan and Japan have a complicated history, but in SABU’s latest slice of cross-cultural interplay each place becomes a kind of refuge from the other. Working largely in Mandarin and with Taiwanese star Chang Chen, SABU returns to a familiar story – the lonely hitman tempted by a normal family life filled with peace and simplicity only to have his dreams taken from him by the spectre of his past. Only this time it isn’t just his past but that of others too. Despite the melancholy air, Mr. Long (ミスター・ロン) is a testament to the power of simple human kindness but also a condemnation of underworld cruelty and its vicelike grip on all who enter its grasp.

Taiwan and Japan have a complicated history, but in SABU’s latest slice of cross-cultural interplay each place becomes a kind of refuge from the other. Working largely in Mandarin and with Taiwanese star Chang Chen, SABU returns to a familiar story – the lonely hitman tempted by a normal family life filled with peace and simplicity only to have his dreams taken from him by the spectre of his past. Only this time it isn’t just his past but that of others too. Despite the melancholy air, Mr. Long (ミスター・ロン) is a testament to the power of simple human kindness but also a condemnation of underworld cruelty and its vicelike grip on all who enter its grasp.

Like the rest of the world, China, or a given generation at least, may be finding itself at something of a crossroads. The past few years have seen a flurry of coming of age dramas in which the melancholy and middle-aged revisit lost love from their youth but Derek Tsang’s Soul Mate (七月与安生, Qīyuè yǔ Anshēng) seems to be speaking to an older kind of melodrama in its examination of passionate friendship pulled apart by time, tragedy, and unspoken emotion. The story is an old one, but Tsang tells it well as its twin heroines maintain their intense, elemental connection even whilst cruelly separated.

Like the rest of the world, China, or a given generation at least, may be finding itself at something of a crossroads. The past few years have seen a flurry of coming of age dramas in which the melancholy and middle-aged revisit lost love from their youth but Derek Tsang’s Soul Mate (七月与安生, Qīyuè yǔ Anshēng) seems to be speaking to an older kind of melodrama in its examination of passionate friendship pulled apart by time, tragedy, and unspoken emotion. The story is an old one, but Tsang tells it well as its twin heroines maintain their intense, elemental connection even whilst cruelly separated. Feng Xiaogang, often likened to the “Chinese Spielberg”, has spent much of his career creating giant box office hits and crowd pleasing pop culture phenomenons from World Without Thieves to Cell Phone and You Are the One. Looking at his later career which includes such “patriotic” fare as Aftershock, Assembly, and

Feng Xiaogang, often likened to the “Chinese Spielberg”, has spent much of his career creating giant box office hits and crowd pleasing pop culture phenomenons from World Without Thieves to Cell Phone and You Are the One. Looking at his later career which includes such “patriotic” fare as Aftershock, Assembly, and  Youth looks ahead to age with eyes full of hope and expectation, but age looks back with pity and disappointment. Adapting her father’s novel, Liu Yulin joins the recent movement of disillusionment epics coming out of China with Someone to Talk to (一句頂一萬句, Yī Jù Dǐng Yīwàn Jù). Arriving at the same time as another adaptation of a Liu Zhenyun novel, I am Not Madame Bovary, Someone to Talk to takes a less comical look at the modern Chinese marriage with all of its attendant sorrows and ironies, a necessity and yet the force which both defines and ruins lives. Communism believes love is a bourgeois distraction and the enemy of the common good (it may have a point), but each of these lonely souls craves romantic fulfilment, a soulmate with whom they might not need to talk. The desire for someone they can connect with an elemental level becomes the one thing they cannot live without.

Youth looks ahead to age with eyes full of hope and expectation, but age looks back with pity and disappointment. Adapting her father’s novel, Liu Yulin joins the recent movement of disillusionment epics coming out of China with Someone to Talk to (一句頂一萬句, Yī Jù Dǐng Yīwàn Jù). Arriving at the same time as another adaptation of a Liu Zhenyun novel, I am Not Madame Bovary, Someone to Talk to takes a less comical look at the modern Chinese marriage with all of its attendant sorrows and ironies, a necessity and yet the force which both defines and ruins lives. Communism believes love is a bourgeois distraction and the enemy of the common good (it may have a point), but each of these lonely souls craves romantic fulfilment, a soulmate with whom they might not need to talk. The desire for someone they can connect with an elemental level becomes the one thing they cannot live without.

“Time, like a river, flows both day and night” as the narrator of Yang Chao’s poetical return to source Crosscurrent (長江圖, Chang Jiang Tu) tells us early on. Like the crosscurrent of the title, ship’s captain Chun sails forth yet also in retrograde as he chases a love he can never truly embrace. Truth be told, the philosophical poetry of a lonely sailor condemned to sail a predetermined course at the mercy of the winds and tides is often obscure and confused, like the half mad ramblings of one who’s spent too much time all alone at sea. Yet his melancholy passage is more metaphor than reality, or several interconnected metaphors as water yearns for shore but is pulled towards the ocean, a man yearns to free himself of his father’s spirit, and mankind yearns for the land yet disrupts and destroys it in its quest for mastery. Often frustrating in its obscurity, Crosscurrent’s breathtaking visuals are the key to unlocking its meditative sadness as they paint the beautiful landscape in its own conflicting colours.

“Time, like a river, flows both day and night” as the narrator of Yang Chao’s poetical return to source Crosscurrent (長江圖, Chang Jiang Tu) tells us early on. Like the crosscurrent of the title, ship’s captain Chun sails forth yet also in retrograde as he chases a love he can never truly embrace. Truth be told, the philosophical poetry of a lonely sailor condemned to sail a predetermined course at the mercy of the winds and tides is often obscure and confused, like the half mad ramblings of one who’s spent too much time all alone at sea. Yet his melancholy passage is more metaphor than reality, or several interconnected metaphors as water yearns for shore but is pulled towards the ocean, a man yearns to free himself of his father’s spirit, and mankind yearns for the land yet disrupts and destroys it in its quest for mastery. Often frustrating in its obscurity, Crosscurrent’s breathtaking visuals are the key to unlocking its meditative sadness as they paint the beautiful landscape in its own conflicting colours. No ghosts! That’s one of the big rules when it comes to the Chinese censors, but then these “ghosts” are not quite what they seem and belong to the pre-communist era when the people were far less enlightened than they are now. One of the few directors brave enough to tackle horror in China, Raymond Yip Wai-man goes for the gothic in this Phantom of the Opera inspired tale of love and the supernatural set in bohemian ‘30s Shanghai, Phantom of the Theatre (魔宫魅影, Mó Gōng Mèi Yǐng). As expected, the thrills and chills remain mild as the ghostly threat edges closer to its true role as metaphor in a revenge tale that is in perfect keeping with the melodrama inherent in the genre, but the full force of its tragic inevitability gets lost in the miasma of awkward CGI and theatrical artifice.

No ghosts! That’s one of the big rules when it comes to the Chinese censors, but then these “ghosts” are not quite what they seem and belong to the pre-communist era when the people were far less enlightened than they are now. One of the few directors brave enough to tackle horror in China, Raymond Yip Wai-man goes for the gothic in this Phantom of the Opera inspired tale of love and the supernatural set in bohemian ‘30s Shanghai, Phantom of the Theatre (魔宫魅影, Mó Gōng Mèi Yǐng). As expected, the thrills and chills remain mild as the ghostly threat edges closer to its true role as metaphor in a revenge tale that is in perfect keeping with the melodrama inherent in the genre, but the full force of its tragic inevitability gets lost in the miasma of awkward CGI and theatrical artifice. Waking up in a strange place with absolutely no recollection of how you got there is bad enough. Waking up next to a total stranger is another degree of awkward. Waking up not in someone else’s apartment but in a department store furniture showroom is another kind of problem entirely (let’s hope the CCTV cameras were on the blink, eh?). This improbable situation is exactly what has befallen two lonely Beijinger’s in Derek Tsang and Jimmy Wan’s elegantly constructed romantic comedy meets procedural, Lacuna (醉后一夜, Zuì Hòu Yīyè). An extreme number of unexpected events is required to bring these two perfectly matched souls together, but the love gods were smiling on this particular night and, once the booze has worn off, romance looks set to bloom .

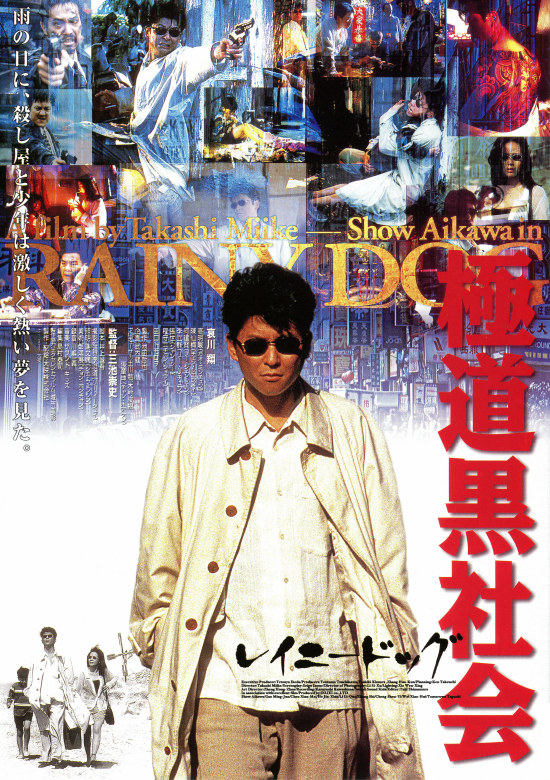

Waking up in a strange place with absolutely no recollection of how you got there is bad enough. Waking up next to a total stranger is another degree of awkward. Waking up not in someone else’s apartment but in a department store furniture showroom is another kind of problem entirely (let’s hope the CCTV cameras were on the blink, eh?). This improbable situation is exactly what has befallen two lonely Beijinger’s in Derek Tsang and Jimmy Wan’s elegantly constructed romantic comedy meets procedural, Lacuna (醉后一夜, Zuì Hòu Yīyè). An extreme number of unexpected events is required to bring these two perfectly matched souls together, but the love gods were smiling on this particular night and, once the booze has worn off, romance looks set to bloom . They say dogs get disorientated by the rain, all those useful smells they use to navigate the world get washed away as if someone had suddenly crumpled up their internal maps and thrown them in the waste paper bin. Yuji (Show Aikawa), the hero of Rainy Dog (極道黒社会, Gokudo Kuroshakai) – the second instalment in what is loosely thought of as Takashi Miike’s Black Society Trilogy, appears to be in a similar position as he hides out in Taipei only to find himself with no home to return to. Miike is not generally known for contemplative mood pieces, but Rainy Dog finds him feeling introspective. A noir inflected, western inspired tale of existential reckoning, this is Miike at his most melancholy but perhaps also at his most forgiving as his weary hitman lays down his burdens to open his heart only to embrace the cold steel of his destiny rather than the warmth of his redemption.

They say dogs get disorientated by the rain, all those useful smells they use to navigate the world get washed away as if someone had suddenly crumpled up their internal maps and thrown them in the waste paper bin. Yuji (Show Aikawa), the hero of Rainy Dog (極道黒社会, Gokudo Kuroshakai) – the second instalment in what is loosely thought of as Takashi Miike’s Black Society Trilogy, appears to be in a similar position as he hides out in Taipei only to find himself with no home to return to. Miike is not generally known for contemplative mood pieces, but Rainy Dog finds him feeling introspective. A noir inflected, western inspired tale of existential reckoning, this is Miike at his most melancholy but perhaps also at his most forgiving as his weary hitman lays down his burdens to open his heart only to embrace the cold steel of his destiny rather than the warmth of his redemption. Trains! They seem to be the latest big thing in Chinese cinema, but at least Railroad Tigers (铁道飞虎, Tiědào Fēi Hǔ) has more rolling stock on offer than the disappointingly CGI enhanced effort which formed the finale of

Trains! They seem to be the latest big thing in Chinese cinema, but at least Railroad Tigers (铁道飞虎, Tiědào Fēi Hǔ) has more rolling stock on offer than the disappointingly CGI enhanced effort which formed the finale of