A down on his luck writer finds himself at the centre of a mystery only how much is truth and how much “fiction”? Based on the novel by Shogo Sato, Hideta Takahata’s Every Trick in the Book (鳩の撃退法, Hato no gekitai-ho) ponders the possibilities of literature as the hero seems to create a fictional world around him in which it is largely unclear whether he is solving a real world mystery or simply imagining one based on his impressions of the strange characters he encounters through the course of his everyday life.

That everyday life is however eventful just in itself. Tsuda (Tatsuya Fujiwara) once won a prestigious literary prize and was destined to become a popular author but hasn’t written anything of note for some time and in fact now largely works as a driver ferrying sex workers around on behalf of his shady boss. The mystery begins when he approaches a man, a rare solo reader in an overnight cafe, and promises to lend him a copy of Peter and Wendy by JM Barrie only to later discover that the man went missing along with his wife and the daughter he had explained was fathered by another man.

Like many of his subsequent encounters it isn’t entirely clear if this meeting really took place or at least as Tsuda said it did or is only part of the novel he is beginning to write. The man, Hideyoshi (Shunsuke Kazama), asks him if it’s a novelist’s habit to begin imagining backstories for everyone he sets eyes on and there may well be some of that even as Tsuda is fond of claiming that amazing things happen around us every day to which we are mostly oblivious. Still, Tsuda probably didn’t expect to be pulled into the orbit of local gangster Kurata (Etsushi Toyokawa) after accidentally passing on counterfeit currency he found by chance. It’s true that most of what’s happening to him is the result of a series of bizarre coincidences or cosmic confluence which has accidentally united this collection of people in an unintended mystery which Tsuda intends to solve in either literal or literary terms.

“It’s all a novelist can do” he later claims in trying to write a better ending for “characters” he has come to like than the one he assumes they “actually” met. But then his editor Nahomi (Tao Tsuchiya) chief worry is that, like his previous novel, Tsuda’s story will contain too much of the “literal” truth which could cause his publishers some legal problems. Part of the reason Tsuda left the industry is apparently because his last book was inspired by a real life affair which was then considered somewhat hurtful and defamatory. For that reason it comes as quite a blow to Nahomi as she begins to investigate and discovers that much of Tsuda’s story lines up with “real” places and events, but then again as he says if you can draw connections between known facts then you begin to see a “hidden” truth which may in its own way be merely his invention.

The film’s Japanese title translates more literally as something like “how to fend off a dove” which does indeed have its share of irony especially considering the meaning the dove symbolism turns out to have in the film but perhaps also hints at the essential absurdity of trying to fight back against something that is otherwise harmless and in fact represents peace. Tsuda may be onto something and nothing, embracing the bizarre serendipity of a writer’s life while trying to recover his creative mojo but embellishing it with more danger and strangeness than it actually has to offer. Then again as his editor discovers, there really is an incinerator it seems anyone can just walk up and use to burn whatever they want including dead bodies, while people in general are full of duplicities all of which keeps the “fake” money circulating as people use it to try to buy things that can’t really be bought. Hideyoshi calls them “miracles”, embracing the strange serendipity of his life as an orphan longing for a family to call his own and unexpectedly finding one which is “real” in someways and “fiction” and in others. Then again, if you believe in something does it really matter if it’s “real” or not? Hideyoshi and Tsuda might say it doesn’t, the publishing company’s lawyers might feel differently, but it seems there really are amazing things going on around us every day if only you stop to look.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

In this brand new, post truth world where spin rules all, it’s important to look on the bright side and recognise the enormous positive power of the lie. 2015’s April Fools (エイプリルフールズ) is suddenly seeming just as prophetic as the machinations of the weird old woman buried at its centre seeing as its central message is “who cares about the truth so long as everyone (pretends) to be happy in the end?”. A dangerous message to be sure though perhaps there is something to be said about forgiving those who’ve misled you after understanding their reasoning. Or, then again, maybe not.

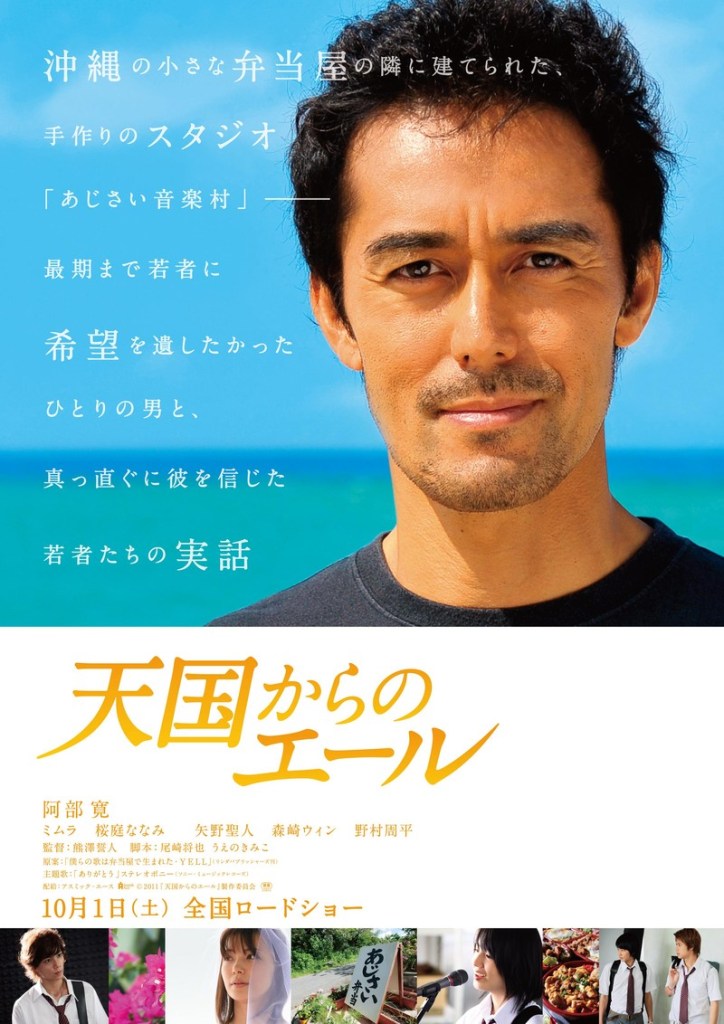

In this brand new, post truth world where spin rules all, it’s important to look on the bright side and recognise the enormous positive power of the lie. 2015’s April Fools (エイプリルフールズ) is suddenly seeming just as prophetic as the machinations of the weird old woman buried at its centre seeing as its central message is “who cares about the truth so long as everyone (pretends) to be happy in the end?”. A dangerous message to be sure though perhaps there is something to be said about forgiving those who’ve misled you after understanding their reasoning. Or, then again, maybe not. Okinawa might be a popular tourist destination but behind the beachside bars and fun loving nightlife there’s a thriving community of local people making their everyday lives here. Just like everywhere else, life can be tough when you’re young and the town’s teenagers lament that there’s just not much for them to do. A small group of high schoolers have formed a rock band but they’re quickly kicked out of their practice spot at school after a series of noise complaints from neighbours.

Okinawa might be a popular tourist destination but behind the beachside bars and fun loving nightlife there’s a thriving community of local people making their everyday lives here. Just like everywhere else, life can be tough when you’re young and the town’s teenagers lament that there’s just not much for them to do. A small group of high schoolers have formed a rock band but they’re quickly kicked out of their practice spot at school after a series of noise complaints from neighbours.