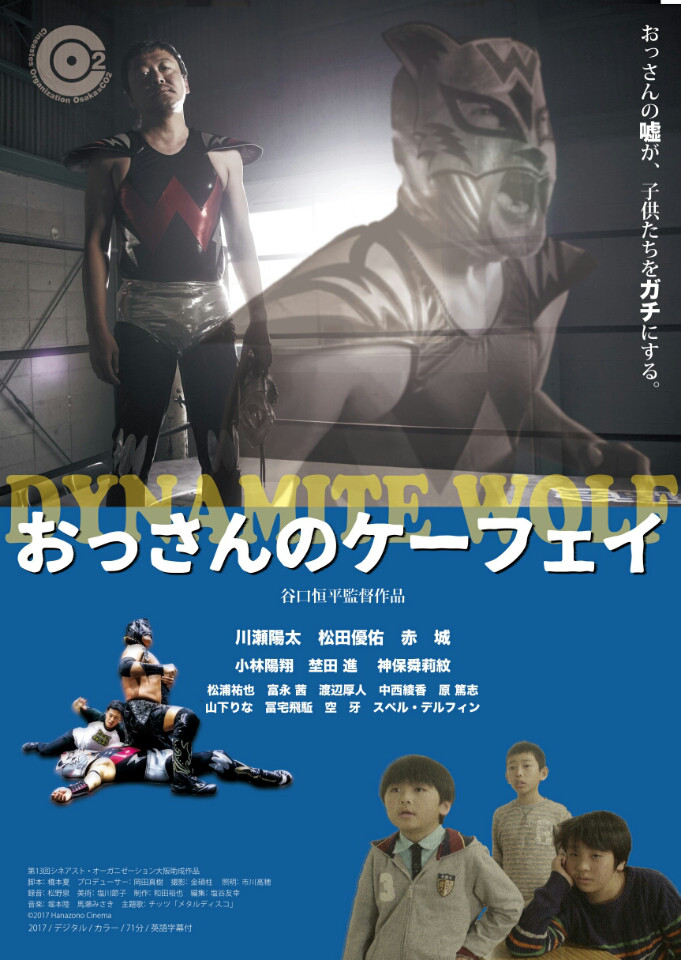

Back in the day, lucha libre-style wrestling was hugely popular in Japan. Tiger Mask, a manga set in the world of Japanese pro-wrestling remains a firm favourite and its eponymous hero has also become a byword for altruistic philanthropy as well-meaning anonymous donors donate expensive gifts such as Japanese school backpacks to orphanages in Tiger Mask’s name. Sadly, pro-wrestling is no longer as high-profile as it once was and has left mainstream television screens far behind even if it still maintains a small but dedicated fanbase. Kohei Taniguchi’s Dynamite Wolf (おっさんのケーフェイ, Ossan no Kefei) is out to change all that by shining a spotlight on this almost forgotten phenomenon of crazy outfits, killer moves, and camp showmanship.

Back in the day, lucha libre-style wrestling was hugely popular in Japan. Tiger Mask, a manga set in the world of Japanese pro-wrestling remains a firm favourite and its eponymous hero has also become a byword for altruistic philanthropy as well-meaning anonymous donors donate expensive gifts such as Japanese school backpacks to orphanages in Tiger Mask’s name. Sadly, pro-wrestling is no longer as high-profile as it once was and has left mainstream television screens far behind even if it still maintains a small but dedicated fanbase. Kohei Taniguchi’s Dynamite Wolf (おっさんのケーフェイ, Ossan no Kefei) is out to change all that by shining a spotlight on this almost forgotten phenomenon of crazy outfits, killer moves, and camp showmanship.

Middle schooler Hiroto is the most ordinary of little boys. He has two good friends, but no particular, hopes, dreams, talents, or aspirations. When his teacher assigns the class a special project in which they are supposed to come up with some kind of act they can do before the class to showcase a special skill, Hiroto is at a loss. His friend Takuto is going to whilstle whilst recent transfer student from Tokyo, Naoya, is going to show off his English but neither of them have any suggestions to help Hiroto figure out what his special talent is. Things only get worse when his mother catches sight of another boy, Teruo, on television being showcased on the news because of his dedication to dance, and insists Hiroto go to dance classes too which he is not really interested in. On the way back however his life changes when he spots a man in a strange shiny suit standing outside smoking. Invited inside, Hiroto witnesses the last ever fight of the legendary wrestler Dynamite Wolf and becomes instantly hooked on Japanese pro-wrestling.

Times being what they are, pro-wrestling is not the coolest of hobbies but Hiroto is undeterred. Running into an old man he thinks might by the real Dynamite Wolf, Hiroto starts training to become a wrestler and roping Takuto and Naoya in to practice too. As Naoya points out, anyone seeing three young kids wrestling around with a 50-year-old man would probably call the police but Mr. Sakata really is just interested in spreading the love of wrestling to the younger generation.

Despite the anti-wrestling sentiment, there’s something quite refreshing about the boys who like boyband-style dancing being the bullies and not the bullied. Teruo is a nasty piece of work and a spoilt brat thanks to the fact his dad is the head of the PTA but his love of dance is never questioned or mocked and is even favoured over the comparatively more “manly” hobby of wrestling.

Like any good kids movie, Dynamite Wolf is equally about the power of friendship as it is about reviving pro-wrestling. Teruo starts out as a little thug, behaving with impunity and making Hiroto’s life a nightmare simply because he’s not quite like them. However, once he learns some unpleasant stuff about his dad his world crumbles and he reforms to become a wrestling ally and all round better person.

Hiroto proves far more mature than his mentor who has repeatedly failed to achieve his dreams and now exists in a strange kind of perpetual childhood, trapped inside his own delusions. Unfairly branded a liar, Sakata does like a few tall tales and remains embittered about his lack of his success. His life has been about wrestling, but the ring has never accepted him and now he spends all his time beating up a blow-up doll on the beach and visiting sex workers for lucha libre workouts. His desire to mentor the boys is a noble one in the service of wrestling, but then again are wrestling skills really worth anything when outsiders simply ignore the rules and go for a one punch knock out?

Taking on a Rocky vibe, the question stops being about winning or losing but about finding your passion and then giving it your all even if it doesn’t end in the predictable fashion. Pro-wrestling might be over the top and campy, more about showmanship and ritual than signature moves technical skill but the friendships, loyalties, and sense of fair play are values which deserve to be fought for – mask on or off.

Dynamite Wolf was screened at the 17th Nippon Connection Japanese Film Festival.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

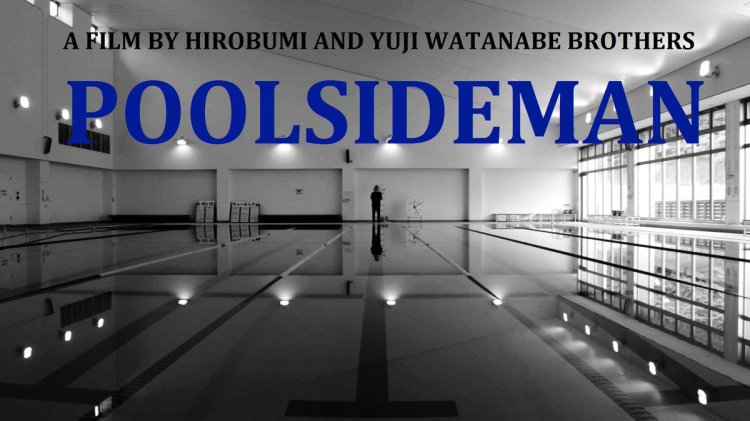

Around halfway through Poolsideman (プールサイドマン), the director himself playing an overly chatty colleague of the film’s protagonist, embarks on a lengthy rant about encroaching middle-age which is instantly relatable to those who find themselves at a similar juncture. He’s sure the world seemed better when he was a child, there wasn’t all of this distress and anxiety – everything just seemed like it would go on forever but time has inexplicably sped up with a series of rapid changes packed into recent years. The life of a poolsideman is improbably intense, or at least it is for Mizuhara (Gaku Imamura) whose days are all the same but filled with tension and the low simmer of something waiting to explode. Loosely inspired by the real life case of a man who left Japan for the Middle East with the idea of joining Isis, Poolsideman wants to explore why such a surreal thing might happen but finds it all too plausible.

Around halfway through Poolsideman (プールサイドマン), the director himself playing an overly chatty colleague of the film’s protagonist, embarks on a lengthy rant about encroaching middle-age which is instantly relatable to those who find themselves at a similar juncture. He’s sure the world seemed better when he was a child, there wasn’t all of this distress and anxiety – everything just seemed like it would go on forever but time has inexplicably sped up with a series of rapid changes packed into recent years. The life of a poolsideman is improbably intense, or at least it is for Mizuhara (Gaku Imamura) whose days are all the same but filled with tension and the low simmer of something waiting to explode. Loosely inspired by the real life case of a man who left Japan for the Middle East with the idea of joining Isis, Poolsideman wants to explore why such a surreal thing might happen but finds it all too plausible. Times change so quickly. The “danchi” was a symbol of post-war aspiration and rising economic prosperity as it sought to give young professionals an affordable yet modern, convenient way of life. The term itself is a little hard to translate though loosely enough just means a housing estate but unlike “The Projects” (団地, Danchi) of the title, these are generally not areas of social housing or lower class neighbourhoods but a kind of vertical village which one should never need to leave (except to go to work) as they also include all the necessary amenities for everyday life from shops and supermarkets to bars and restaurants. Nevertheless, aspirations change across generations and what was once considered a dreamlike promise of futuristic convenience now seems run down and squalid. Cramped apartments with tiny rooms, washing machines on the balconies, no lifts – young people do not see these things as convenient and so the danchi is mostly home to the older generation, downsizers, or the down on their luck.

Times change so quickly. The “danchi” was a symbol of post-war aspiration and rising economic prosperity as it sought to give young professionals an affordable yet modern, convenient way of life. The term itself is a little hard to translate though loosely enough just means a housing estate but unlike “The Projects” (団地, Danchi) of the title, these are generally not areas of social housing or lower class neighbourhoods but a kind of vertical village which one should never need to leave (except to go to work) as they also include all the necessary amenities for everyday life from shops and supermarkets to bars and restaurants. Nevertheless, aspirations change across generations and what was once considered a dreamlike promise of futuristic convenience now seems run down and squalid. Cramped apartments with tiny rooms, washing machines on the balconies, no lifts – young people do not see these things as convenient and so the danchi is mostly home to the older generation, downsizers, or the down on their luck.

Tsugumi Ohba and Takashi Obata’s Death Note manga has already spawned three live action films, an acclaimed TV anime, live action TV drama, musical, and various other forms of media becoming a worldwide phenomenon in the process. A return to cinema screens was therefore inevitable – Death Note: Light up the NEW World (デスノート Light up the NEW World) positions itself as the first in a possible new strand of the ongoing franchise, casting its net wider to embrace a new, global world. Directed by Shinsuke Sato – one of the foremost blockbuster directors in Japan responsible for Gantz,

Tsugumi Ohba and Takashi Obata’s Death Note manga has already spawned three live action films, an acclaimed TV anime, live action TV drama, musical, and various other forms of media becoming a worldwide phenomenon in the process. A return to cinema screens was therefore inevitable – Death Note: Light up the NEW World (デスノート Light up the NEW World) positions itself as the first in a possible new strand of the ongoing franchise, casting its net wider to embrace a new, global world. Directed by Shinsuke Sato – one of the foremost blockbuster directors in Japan responsible for Gantz,

Parks are a common feature of modern city life – a stretch of green among the grey, but it’s important to remember that there has not always been such beautiful shared space set aside for public use. Natsuki Seta’s light and breezy youth comedy, Parks (PARKS パークス), was commissioned in celebration of the centenary of the Tokyo park where the majority of the action takes place, Inokashira. Mixing early Godardian whimsy with new wave voice over and the kind of innocent adventure not seen since the Kadokawa idol days, Parks is a sometimes melancholy, wistful tribute to a place where chance meetings can define lifetimes as well as to brief yet memorable summers spent with gone but not forgotten friends doing something which seems important but which in retrospect may be trivial.

Parks are a common feature of modern city life – a stretch of green among the grey, but it’s important to remember that there has not always been such beautiful shared space set aside for public use. Natsuki Seta’s light and breezy youth comedy, Parks (PARKS パークス), was commissioned in celebration of the centenary of the Tokyo park where the majority of the action takes place, Inokashira. Mixing early Godardian whimsy with new wave voice over and the kind of innocent adventure not seen since the Kadokawa idol days, Parks is a sometimes melancholy, wistful tribute to a place where chance meetings can define lifetimes as well as to brief yet memorable summers spent with gone but not forgotten friends doing something which seems important but which in retrospect may be trivial.

When tragedy strikes the one thing you ought to be able to rely on is your family, but when the tragedy occurs within that sacred space which exits between you what is to be done? Yosuke Takeuchi’s The Sower (種をまく人, Tane wo Maku Hito) attempts to provide an answer whilst putting one very ordinary, loving and forgiving family through a series of tests and tragedies. Lies, regret, and despair conspire to ruin the lives of four once happy people but even in the midst of such a shocking, unexpected event there is still time to turn towards the sun rather than continuing in the darkness.

When tragedy strikes the one thing you ought to be able to rely on is your family, but when the tragedy occurs within that sacred space which exits between you what is to be done? Yosuke Takeuchi’s The Sower (種をまく人, Tane wo Maku Hito) attempts to provide an answer whilst putting one very ordinary, loving and forgiving family through a series of tests and tragedies. Lies, regret, and despair conspire to ruin the lives of four once happy people but even in the midst of such a shocking, unexpected event there is still time to turn towards the sun rather than continuing in the darkness.

Towards the end of the 60s and faced with the same problems as any other studio of the day – namely declining receipts as cinema audiences embraced television, Nikkatsu decided to spice up their already racy youth orientated output with a steady stream of sex and violence. The Roman Porno line took a loftier approach to the “pink film” – mainstream softcore pornography played in dedicated cinemas and created to a specific formula, by putting the resources of a bigger studio behind it with greater production values and acting talent. 40 years on Roman Porno is back. Kazuya Shiraishi’s Dawn of the Felines (牝猫たち, Mesunekotachi) takes inspiration from Night of the Felines by the Roman Porno master Noboru Tanaka but where Tanaka’s film is a raucous comedy following the humorous adventures of its three working girl protagonists, Shiraishi’s is a much less joyous affair as he casts his three lonely heroines adrift in Tokyo’s red light district.

Towards the end of the 60s and faced with the same problems as any other studio of the day – namely declining receipts as cinema audiences embraced television, Nikkatsu decided to spice up their already racy youth orientated output with a steady stream of sex and violence. The Roman Porno line took a loftier approach to the “pink film” – mainstream softcore pornography played in dedicated cinemas and created to a specific formula, by putting the resources of a bigger studio behind it with greater production values and acting talent. 40 years on Roman Porno is back. Kazuya Shiraishi’s Dawn of the Felines (牝猫たち, Mesunekotachi) takes inspiration from Night of the Felines by the Roman Porno master Noboru Tanaka but where Tanaka’s film is a raucous comedy following the humorous adventures of its three working girl protagonists, Shiraishi’s is a much less joyous affair as he casts his three lonely heroines adrift in Tokyo’s red light district.

Learning to love Tokyo is a kind of suicide, according to the heroine of Yuya Ishii’s love/hate letter to the Japanese capital, The Tokyo Night Sky is Always the Densest Shade of Blue (夜空はいつでも最高密度の青色だ, Yozora wa Itsudemo Saiko Mitsudo no Aoiro da). This city is a mess of contradictions, a huge sprawling metropolis filled with the anonymous masses and at the same time so tiny you can find yourself running into the same people over and over again. Inspired by the poems of Tahi Saihate, The Tokyo Night Sky is at once a meditative contemplation of city life and an awkward love story between two lost souls who somehow find each other in its crowded backstreets.

Learning to love Tokyo is a kind of suicide, according to the heroine of Yuya Ishii’s love/hate letter to the Japanese capital, The Tokyo Night Sky is Always the Densest Shade of Blue (夜空はいつでも最高密度の青色だ, Yozora wa Itsudemo Saiko Mitsudo no Aoiro da). This city is a mess of contradictions, a huge sprawling metropolis filled with the anonymous masses and at the same time so tiny you can find yourself running into the same people over and over again. Inspired by the poems of Tahi Saihate, The Tokyo Night Sky is at once a meditative contemplation of city life and an awkward love story between two lost souls who somehow find each other in its crowded backstreets.

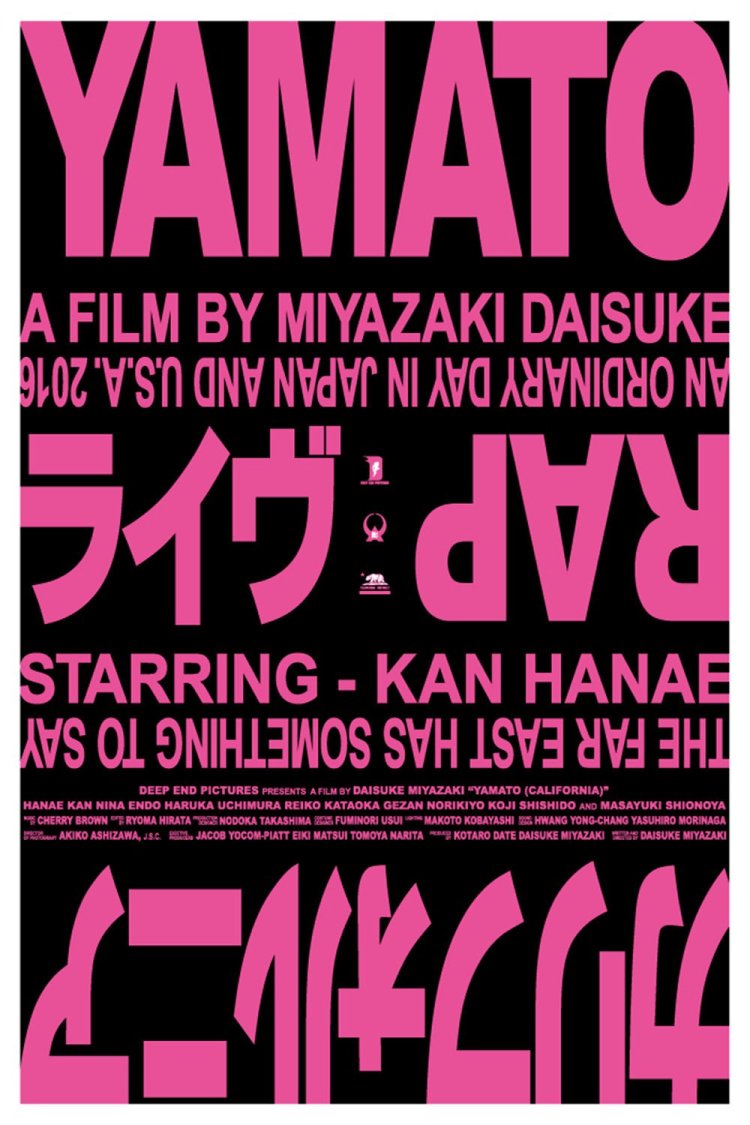

When you think of the American military presence in Japan, your mind naturally turns to Okinawa but the largest mainland US base is actually located not so far from Tokyo in a small Japanese town called Yamato which is also the ancient name for the modern-day country. The US has been a constant presence since the end of the second world war prompting resistance of varying degrees from both left and right either in resentment at perceived complicity in American foreign policy, or the desire to reform the pacifist constitution and rebuild an independent army capable of defending Japan alone. Daisuke Miyazaki’s second feature, Yamato (California) (大和(カリフォルニア) dramatises this long-standing issue through exploring the life of hip-hop enthusiast and Yamato resident Sakura (Hanae Kan) who idolises an art form born of political oppression in a country which she also feels oppresses her as a Japanese citizen living on the other side of the fence from land which technically still belongs to the US government.

When you think of the American military presence in Japan, your mind naturally turns to Okinawa but the largest mainland US base is actually located not so far from Tokyo in a small Japanese town called Yamato which is also the ancient name for the modern-day country. The US has been a constant presence since the end of the second world war prompting resistance of varying degrees from both left and right either in resentment at perceived complicity in American foreign policy, or the desire to reform the pacifist constitution and rebuild an independent army capable of defending Japan alone. Daisuke Miyazaki’s second feature, Yamato (California) (大和(カリフォルニア) dramatises this long-standing issue through exploring the life of hip-hop enthusiast and Yamato resident Sakura (Hanae Kan) who idolises an art form born of political oppression in a country which she also feels oppresses her as a Japanese citizen living on the other side of the fence from land which technically still belongs to the US government. “Memories are what warm you up from the inside. But they’re also what tear you apart” runs the often quoted aphorism from Haruki Murakami. SABU seems to see things the same way and indulges an equally surreal side of himself in the sci-fi tinged Happiness (ハピネス). Memory, as the film would have it, both sustains and ruins – there are terrible things which cannot be forgotten, no matter how hard one tries, while the happiest moments of one’s life get lost among the myriad everyday occurrences. Happiness is the one thing everyone craves even if they don’t quite know what it is, little knowing that they had it once if only for a few seconds, but if the desire to attain “happiness” is itself a reason for living could simply obtaining it by technological means do more harm than good?

“Memories are what warm you up from the inside. But they’re also what tear you apart” runs the often quoted aphorism from Haruki Murakami. SABU seems to see things the same way and indulges an equally surreal side of himself in the sci-fi tinged Happiness (ハピネス). Memory, as the film would have it, both sustains and ruins – there are terrible things which cannot be forgotten, no matter how hard one tries, while the happiest moments of one’s life get lost among the myriad everyday occurrences. Happiness is the one thing everyone craves even if they don’t quite know what it is, little knowing that they had it once if only for a few seconds, but if the desire to attain “happiness” is itself a reason for living could simply obtaining it by technological means do more harm than good?