Jeong Chang-hwa is better known for the films he made with Shaw Brothers in Hong Kong, including the iconic King Boxer which helped to kick start the Kung Fu craze of the 1970s, than for earlier films he made in his native Korea. Nevertheless, while he was there he also instrumental in creating a new genre of Korean swordplay films with A Wandering Swordsman And 108 Bars of Gold and 1967’s A Swordsman In The Twilight (황혼의 검객, Hwanghonui Geomgaek).

Drawing inspiration from both Japanese samurai movies and King Hu’s wuxia dramas, the film is set in 1691 and like many Korean historical dramas revolves around intrigue in the court. Our hero is however not a high ranking courtier but as he describes himself a struggling vassal who was lucky to get his job as a lowly palace guard because he has no real connections nor does he come from a prominent family and his skills and long years of study mean almost nothing in this society ruled by status. The more things change, the more they stay the same. In any case, he was not unhappy with his life, got on well with his father-in-law, a poor scholar, and had a loving wife and daughter, who like him, valued human decency over ambition.

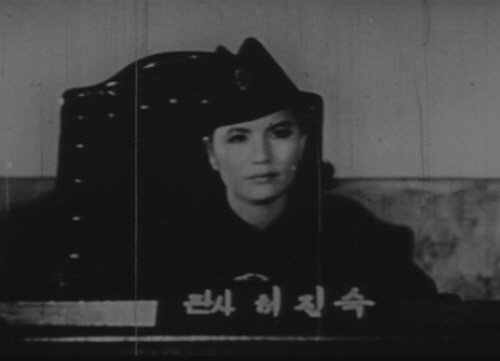

But it’s that gets them into trouble when the venomous Lady Jang stages a palace coup to usurp the position of rightful queen, Min. Queen Min is depicted as a shining example of traditional femininity and idealised womanhood. Though the situation she finds herself in is unfair, she bears it with good grace and refuses the small comforts others offer her saying only that she is a sinner and it’s only right she suffers this way for displeasing the king. Hyang-nyeo (Yoon Jeong-hee), wife of swordsman Tae-won (Namkoong Won), was once her servant and shares her birthday so feels an especial connection to her. Pitying Queen Min seeing her forced to walk barefoot through the mud she offers her shoes and for this crime is hounded by the Jang faction on account of her supposed treason.

Having taken the local governor and his clerk, who are also against the Jang faction but don’t know how to oppose it, hostage, Tae-won narrates his long sad story and reasons for his desire for revenge against corrupt courtier Oh Gi-ryong (Heo Jang-kang) who, it seems, is also motivated by resentment and sexual jealousy after having once proposed to Hyang-nyeo but been instantly rejected by her father who did not wish to marry his daughter off to a thug. As such, he comes to embody the evils of the feudal order in his casual cruelty and pettiness. When we’re first introduced to Tae-won he saves a young woman who was about to be dragged off by Gi-ryong’s henchmen presumably as a consort for their immediate boss, Gi-ryong’s right-hand man, but is warned by the other villagers that he should leave town quickly else the Jang gang will be after him. That is however, exactly what Tae-won wants. He fights a series of duels with Gi-ryong, the first of which ends with Gi-ryong simply running away when Tae-won breaks his sword and in their final confrontation he resorts to the cowardly use of firearms not to mention an entire squad of minions pitched solely against a wounded Tae-won and the unarmed governor.

What it comes down to is a last stand by men who know the right path and are now willing to defend it rather than turn a blind eye to injustice. Tae-won’s own brother (Park Am) had thrown his lot in with Gi-ryong in the hope of personal advancement, willingly aligning himself with the winning side and complicit in its dubious morality. This of course puts him in a difficult position, though he implies he will be prepared to sacrifice Tae-won and his family if necessary even if he also tries to find a better solution such as suggesting Tae-won kill Queen Min to prove his loyalty to the Jang faction. In an odd way, it speaks to the contemporary era as a treatise on how to live under an authoritarian regime not to mention the creeping heartlessness of an increasingly capitalistic society.

This sense personal rebellion may owe more to the jianghu sensibility found in the wuxia movies of King Hu than to the righteous nobility of the samurai film even if the ending strongly echoes chanbara epics in which the hero is displaced from his community and condemned to wander as a perpetual outlaw in a society which does not live up to his ideals. While staging beautifully framed action sequences such as fight at a rocky brook, Jeong undoubtedly draws inspiration from Hu in the use of trampolines and majestic jumps that have an almost supernatural quality. The sword fights are largely bloodless until the final confrontation but also violent and visceral. Gi-ryong’s henchman plays with a minion he feels has betrayed him by lightly scratching his throat before going in for the kill and such cruelty seems to be a hallmark of the Jang faction. But despite the seeming positivity of the ending in which a kind of solidarity has been discovered between Tae-won and the governor, the film ends on an ambivalent note with the fate of the nation still unknown as Lady Jang stoops to shamanic black magic to hold sway and darkness, the lingering shadows of authoritarianism, still hang over the swordsman even if he is in a way free as s rootless wanderer no longer quite bound by feudal constraint.

A Swordsman in the Twilight screened as part of Echoes in Time: Korean Films of the Golden Age and New Cinema.