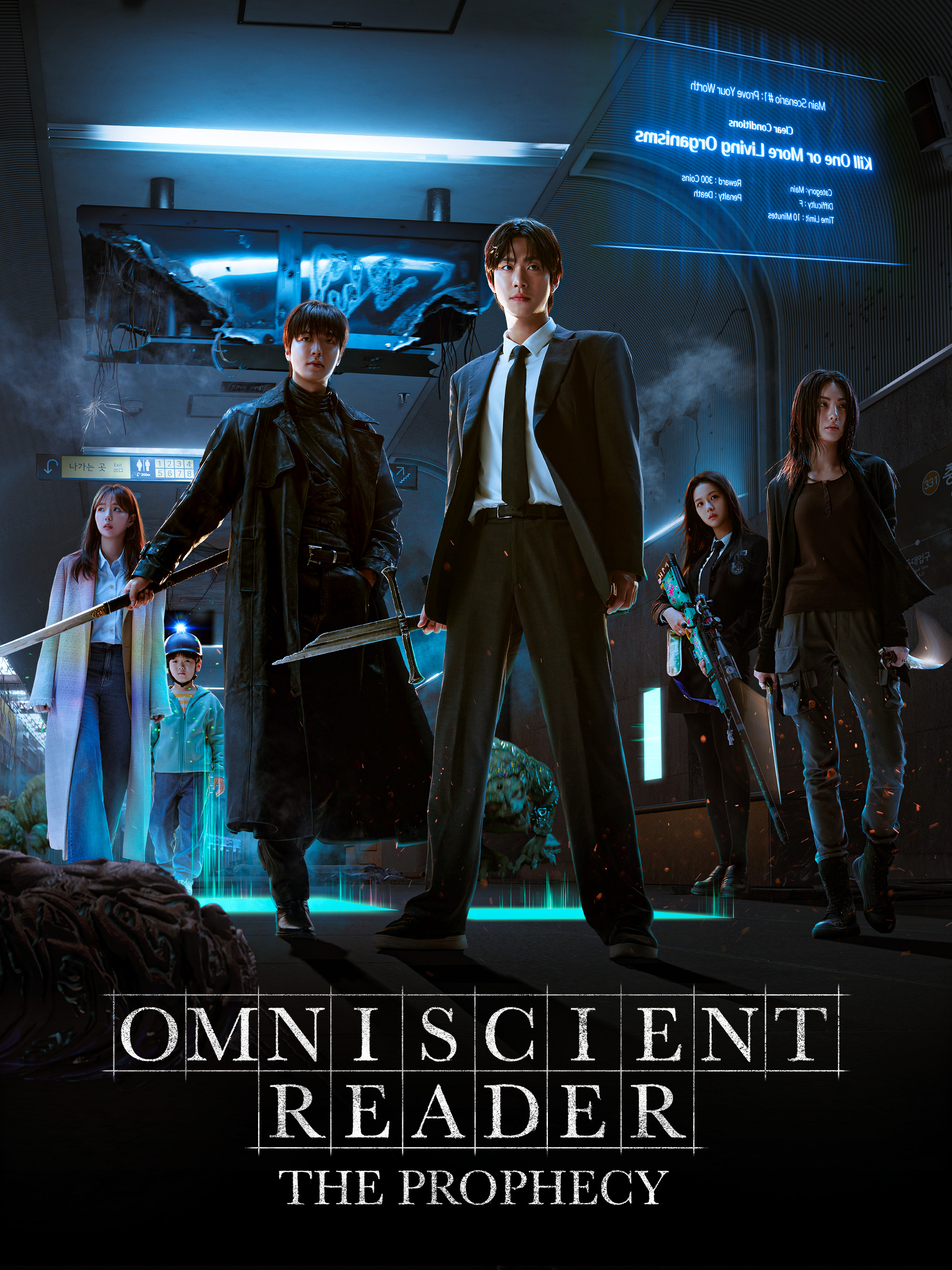

Fed up with the ending of a web novel he’s been reading since his teens, Dokja (Ahn Hyo-seop) sends the author a message. By this stage, he’s the only reader left, a kind of “lone survivor”, if you will. But he tells the author that the ending has disappointed him and that he can’t accept that the main theme was that it’s alright to sacrifice the lives of others so that you alone can live. Adapted from the popular webtoon, Kim Byung-woo’s Omniscient Reader: The Prophecy (전지적 독자 시점, Jeonjijeok Dokja Sijeom) is in part about the conflict between nihilistic pragmatism and selfishness, and a pure-hearted altruism that insists it’s possible for us all to survive and that surviving alone would be pointless anyway.

It only obliquely, however, touches on these themes in how they relate to the contemporary society in hinting at the destructive effects of capitalism. Dokja is the hero of this story, but he’s also a face in the crowd as a member of a constant stream of office workers on their way to work, not really so different from little ants squeezed between the fingers of powerful elites. Dokja at least feels himself to have lost out in this lottery, a contract worker let go by a conglomerate, while his sleazy boss Mr Han (Choi Young-joon) slobbers all over his female colleague, Sangha (Chae Soo-bin), who unlike him is no longer wedded to the corporate philosophy and is considering striking out on her own to do something that interests her personally. Perhaps the novel ending on the same day as his contract felt a little bit to much like the end of a world, which is what pushed him to write a message that in other ways seems uncharacteristically mean.

But then the author tells him that if he doesn’t like this ending he can write his own, perhaps obliquely reminding him that he is free to change his future if he wants. Nevertheless, Dokja is soon thrown into the world of the novel where he is faced with a series of scenarios where he must choose whether to sacrifice the lives of others in order to save his own for the entertainment of celestial beings who watch the whole thing via live streams and occasionally sponsor interesting players. Dokja has an advantage in that he already knows what’s going to happen, but is also aware that things don’t always go the way they should and his own actions change the course of the narrative. He’s convinced that he has to save the “hero”, Jung-hyeok (Lee Min-ho), or the fantasy world will end, killing everyone inside it, but never really considers that he too can be the protagonist of his own story.

He remains committed, however, that the only way to survive is through mutual solidarity even if he scoffs at the quasi-communist mentality at the Geumho subway station correctly guessing that it’s all a scam being run by a corrupt politician which muddies the water somewhat when it comes to the film’s politics. In any case, Dokja seems to believe that he must save Jung-hyeok not just physically but spiritually in proving to him that his nihilistic viewpoint is mistaken and the only way for them to survive is to support each other by pooling their skills and resources. In dealing with his own trauma and guilt over having once sacrificed someone else to ensure his own survival, Dokja is able to write a new ending for himself surrounded by his companions rather than as a lone survivor roaming a ruined land with nothing to look forward to except death.

On the other hand, perhaps it’s true that he thinks he needs a hero to save him rather than realising that he is also the hero of this story, while the fantasy world too is driven by capitalistic mentality in which Dokja must amass coins to be able to level up or literally buy his survival. Occasionally he wavers, wondering if the others have a point when they tell him he’s being foolish and should learn to just save himself no matter what happens to anyone else, but otherwise remains committed to rejecting the premise of the original novel’s nihilistic ending in insisting that there’s a way for us all to survive if only we can learn to be less selfish, trust each other, and work for the good of all.

Omniscient Reader: The Prophecy is available in the UK on digital download from 15th December.

UK Trailer (English subtitles)