After a couple of hundred years of corporatising culture, sham apologies have become an unfortunate phenomenon all over the world. Corporations in particular will often offer a fairly meaningless apology that acknowledges a minimal level of responsibility but does not bind them to recompense those they’ve wronged nor put right anything that their conduct has made wrong. The problem is that an apology has become a kind of sticking plaster that allows us all to move on but doesn’t really solve anything and may even prevent us from doing so because it turns us all into accidental liars who are primed to say “sorry” to make the situation go away even it wasn’t actually our fault.

That’s essentially what happens to Seiichi (Go Ayano), previously an unremarkable primary school teacher with a teenage son of his own and an apparently happy home. Inspired by a real life case, Takashi Miike’s courtroom drama Sham (でっちあげ ~殺人教師と呼ばれた男, Detchiage: Satsujin Kyoshi to Yobareta Otoko) flirts with ambiguities but in keeping with its themes eventually descends into a defence of the well-meaning man as its hero becomes so embroiled in the injustice being done to him that he doesn’t see that he is not entirely blameless. Though we’re first introduced to him as the “homicidal teacher” the papers describe him as, the film’s title leaves us in no doubt that his account is the truer. But it remains a fact that during his conversation with Ritsuko (Ko Shibasaki), the mother of the boy Seiichi is accused of racially bullying, he did remark that Takuto’s American grandfather may explain his unique characteristics which is perhaps within the realms of thoughtless things well-meaning people say in awkward conversations but hints at a level of latent societal prejudice. In any case, that the fact his conversation with Ritsuko ended up drifting towards subjects like bloodlines and the Pacific War is not ideal, while Seiichi should probably have been more mindful of his politically neutral position as an educator.

Likewise, he doesn’t dispute that he tapped Takuto lightly on the cheek to “educate” him that it hurt when he slapped another boy, Junya, who, according to Seiichi, he was bullying. He probably shouldn’t have done this either, even if some may see it merely as common sense in teaching the children that violence is wrong, as ironic as that may be. In any case, the film is on Seiichi’s side and insistent that he did not treat Takuto any differently on account of his non-Japanese ancestor nor spout off any of the racist nonsense that Ritsuko attributes to him. But the major problem is that Seiichi is mild-mannered and also a product of this society. He tries to protest his innocence, but is pressured by his headmaster to apologise anyway which is, of course, a form of lying, something they discourage the children from doing. In the end he goes along with it, because it’s easier to just say “sorry” and hope it goes away rather than address the real issues.

It’s this sham society that the film seems to be critiquing, even if its message gets lost among its intertwining plot threads as Seiichi effectively finds himself bullied by an empowered tabloid media formenting mob justice against what it brands a far-right fascist teacher as a means of selling papers through generating outrage. While he is scrutinised and scorned, no one bothers to look into Ritsuko’s story which is already full of holes such as why, if she’s so protective as a mother, she waited for her son to be a victim of “corporal punishment” 18 times before complaining to the school. Little motivation is given for Ritusko’s actions, though Miike films her and her husband with an an almost vampiric sense of unease as they appear eerily in black on their way to the school. Unhinged herself, the answers may lie in Ritsuko’s own childhood and her yearning for a protective mother figure, not to mention the sophistication of being a child returning from abroad with good education and prospects for the future.

Seiichi refocuses his closing statement on Takuto, insisting that he doesn’t blame him for “lying”, but it’s perhaps also try that he is a kind of victim too whose own actions can only be explained by a closer look at his relationship with his mother and familial environment. But it turns out that it really is easier to just say “sorry” and move on. Even the psychiatrists seem more interested in treating Ritsuko like a customer whose wishes must be obeyed than earnestly trying to help Takuto even if his issues don’t seem to be as serious as his mother might have it. According to Seiichi, telling a child off is the purest expression of love. If everyone carries on with sham apologies, nothing really changes and kids like Takuto get forgotten about as everyone falls over themselves to make the situation go away. No one really cares about the truth, and so it becomes an inconvenience to social cohesion in which those who insist on speaking it are hounded down until they agree with the majority and meekly say “sorry” while those in the wrong nod their heads and continue with their lives free of blame or consequence.

Sham screened as part of this year’s Fantasia International Film Festival.

Trailer (English subtitles)

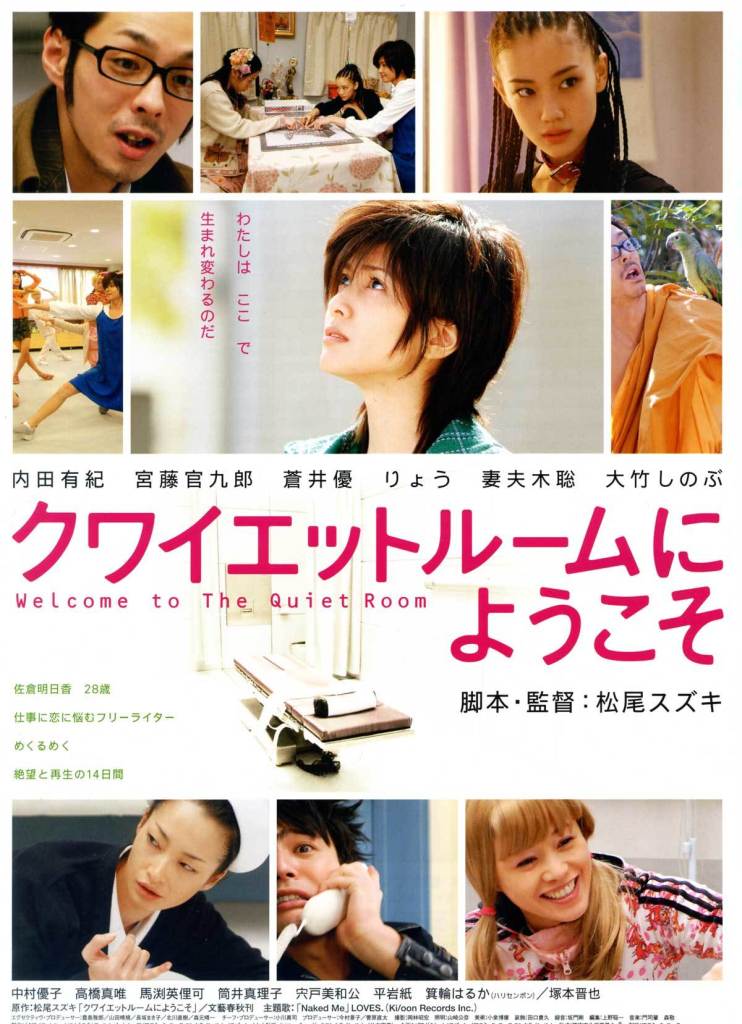

Everyone has those little moments in life where you think “how did I get here?”, but thankfully most of them do not occur strapped to a table in an entirely white, windowless room. This is, indeed, where the heroine of Suzuki Matsuo’s adaptation of his own novel Welcome to the Quiet Room (クワイエットルームにようこそ, Quiet Room ni Yokoso) finds herself after a series of events she can’t remember but which seem to have involved pills and booze. A much needed wake up call, Asuka’s spell in the Quiet Room provides a long overdue opportunity to slow down and take a long hard look at herself but self knowledge can be a heavy burden.

Everyone has those little moments in life where you think “how did I get here?”, but thankfully most of them do not occur strapped to a table in an entirely white, windowless room. This is, indeed, where the heroine of Suzuki Matsuo’s adaptation of his own novel Welcome to the Quiet Room (クワイエットルームにようこそ, Quiet Room ni Yokoso) finds herself after a series of events she can’t remember but which seem to have involved pills and booze. A much needed wake up call, Asuka’s spell in the Quiet Room provides a long overdue opportunity to slow down and take a long hard look at herself but self knowledge can be a heavy burden.

Below average student buckles down and makes it into a top university? You’ve heard this story before and Nobuhiro Doi’s Flying Colors (ビリギャル, Biri Gyaru) doesn’t offer a new spin on the idea or additional angles on educational policy but it does have heart. Heart, it argues is what you need to get ahead (if you’ll forgive the multilevel punning) as the highest barriers to academic success are the ones which are self imposed. Arguing for a more inclusive, tailor made approach to education which doesn’t instil false hope but does help young people develop self confidence alongside standardised skills, Flying Colors is the story of one popular girl’s journey from anti-intellectual teenage snobbery to the very top of the academic tree whilst healing her divided family in the process.

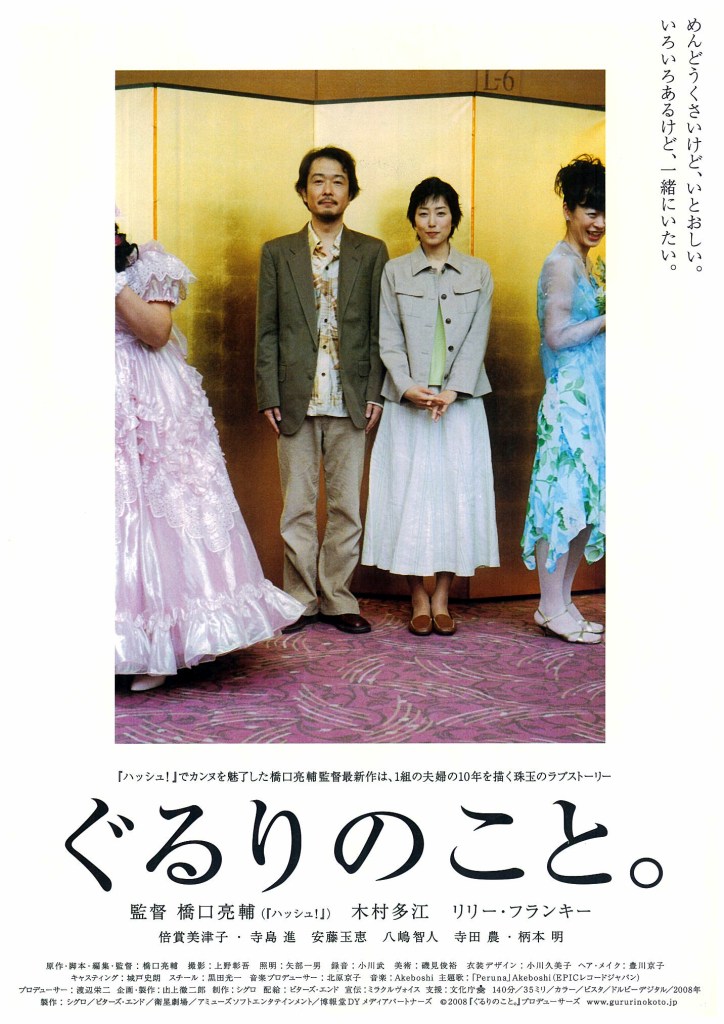

Below average student buckles down and makes it into a top university? You’ve heard this story before and Nobuhiro Doi’s Flying Colors (ビリギャル, Biri Gyaru) doesn’t offer a new spin on the idea or additional angles on educational policy but it does have heart. Heart, it argues is what you need to get ahead (if you’ll forgive the multilevel punning) as the highest barriers to academic success are the ones which are self imposed. Arguing for a more inclusive, tailor made approach to education which doesn’t instil false hope but does help young people develop self confidence alongside standardised skills, Flying Colors is the story of one popular girl’s journey from anti-intellectual teenage snobbery to the very top of the academic tree whilst healing her divided family in the process. Ryosuke Hashiguchi returns after an eight year absence with All Around Us (ぐるりのこと。Gururi no Koto) and eschews most of his pressing themes up this by point by opting to depict a few “scenes from a marriage” in post-bubble era Japan. Set against the backdrop of an extremely turbulent decade which was plagued by natural disasters, terrorism, and shocking criminal activity Hashiguchi shows us the enduring love of one ordinary couple who, finding themselves pulled apart by tragedy, gradually grow closer through their shared grief and disappointment.

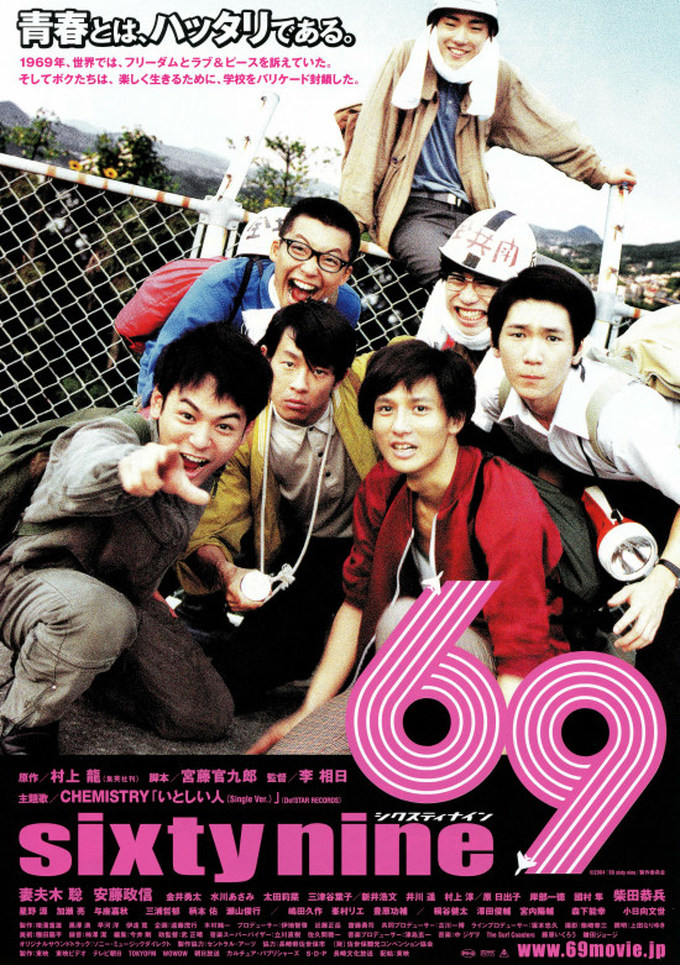

Ryosuke Hashiguchi returns after an eight year absence with All Around Us (ぐるりのこと。Gururi no Koto) and eschews most of his pressing themes up this by point by opting to depict a few “scenes from a marriage” in post-bubble era Japan. Set against the backdrop of an extremely turbulent decade which was plagued by natural disasters, terrorism, and shocking criminal activity Hashiguchi shows us the enduring love of one ordinary couple who, finding themselves pulled apart by tragedy, gradually grow closer through their shared grief and disappointment. Ryu Murakami is often thought of as the foremost proponent of Japanese extreme literature with his bloody psychological thriller/horrifying love story

Ryu Murakami is often thought of as the foremost proponent of Japanese extreme literature with his bloody psychological thriller/horrifying love story