“All I ever wanted was to make everyone happy” claims the father at the centre of Hajime Gonno’s Family Bond (太陽の家, Taiyo no Ie). Once again placing the modern family under the microscope, Gonno’s take is perhaps more traditional than most taking a largely uncritical stance against its extremely patriarchal patriarch whose heart might be in the right place even if his extremely outdated vision of idealised masculinity continues to undermine the idea of family that he is endeavouring to build.

A manly man, Shingo (Tsuyoshi Nagabuchi) proudly introduces himself as a “Master Builder”, tearing up some revised blueprints from his excited newlywed clients who admittedly unreasonably have proposed major changes to the design at the groundbreaking ceremony on their new home. Such fits of artistic temperament are apparently not uncommon, Shingo’s understanding wife Misaki (Naoko Iijima) profusely apologising and later talking him down while reminding him that he might be a master craftsman but he also runs a business and his family need to eat. Shingo prides himself on being a paterfamilias, subscribing to a traditional ideal of masculinity in which a man must be strong to protect his family, and most particularly his women, but that protection extends in the main to the physical. As Misaki later complains, he largely does what he likes because family means no consequences, rarely bothering to consider the feelings of others in his impulsive drive to live in a thoroughly manly way.

That’s perhaps one reason why he walks off the site of the traditional woodframe house he’s being paid to build to have coffee with a pretty young woman, Mei (Ryoko Hirosue), who as it turns out has an ulterior motive in that she wants to sell him an insurance policy. Despite all his life claiming that insurance is for cowards, Shingo signs as gesture of patriarchal solidarity helping out a struggling single mother while perhaps harbouring sightly less altruistic intensions. Nevertheless, it’s her son Ryusei that he’s eventually taken by, struck by the loneliness in his eyes as a boy without a father and taking it upon himself to fulfil that role. For her part, Mei is disturbingly unconcerned by this strange, over friendly, middle-aged man with a strong interest in her young son, encouraging Ryusei to hang out with him expressly because Shingo signed a policy with her as if she were in a sense loaning him out in exchange. In any case, it’s difficult to believe a modern woman would be entirely happy about Shingo’s well-meaning fathering, transmitting this extremely problematic, toxic masculinity to a new generation in instructing Ryusei that he needs to get strong because it’s a man’s responsibility to “protect womenfolk” and Ryusei’s to protect his mother as the man of the house.

These outdated chauvinistic ideas also undermine his relationships with his wife and children, teenage daughter Kanna (Mayu Yamaguchi) resentful at his bond with a random little boy whom he seems to be grooming as a replacement son and potential heir having already alienated his adopted son and apprentice Takashi (Eita Nagayama). Kanna, studying to become an architect, resents her father for his sexism, largely ignoring her because she is a girl and therefore in his eyes unable to assume the family business. Takashi meanwhile resents him because he sent him off to apprentice as a plasterer rather than training him in carpentry as if suggesting he didn’t have what it takes to become a master builder himself. Both of them are hurt by his desire to simply get a new son in its implication that they were never good enough, a feeling compounded by the fact that they are both adopted. Shingo later signals something similar himself when Ryusei’s estranged birth father resurfaces, immediately backing off believing that he couldn’t win against blood as if that really is everything.

“It’s all a big lie” Kanna and Takashi yell on different occasions trying to get through to their irritatingly distant father whose manly code means he doesn’t engage with emotion or feel the need to respond to their distress, eventually striking Kanna for her disrespect and kicking her out of the house. Of course, he doesn’t really mean it but it’s just another example of the ways his problematic manliness continues to destroy his relationships, Takashi also apparently harbouring resentment towards him for his unreconstructed chauvinism in his many affairs believing his desire to help Mei is just him getting up to his old tricks again. What Shingo discovers however is that he’ll have to literally repair his family through building it anew by helping Mei and Ryusei do the same as her estranged husband reassumes his male responsibility to protect his family. In essence, he’s forced to accept the family he has rather than chasing a better one, drawing a clear divide in building a house for Ryusei and his parents which is separate from his own while entreating his children to return to him through getting them to help build it. Shingo might not have changed, still defiantly patriarchal, but he has perhaps begun to accept that family is a mutual construct that requires strong support. In the end you have to build it together or the structure won’t hold.

Family Bond streams in the US via the Smart Cinema app Aug. 28 to Sept. 12 as part of this year’s New York Asian Film festival.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

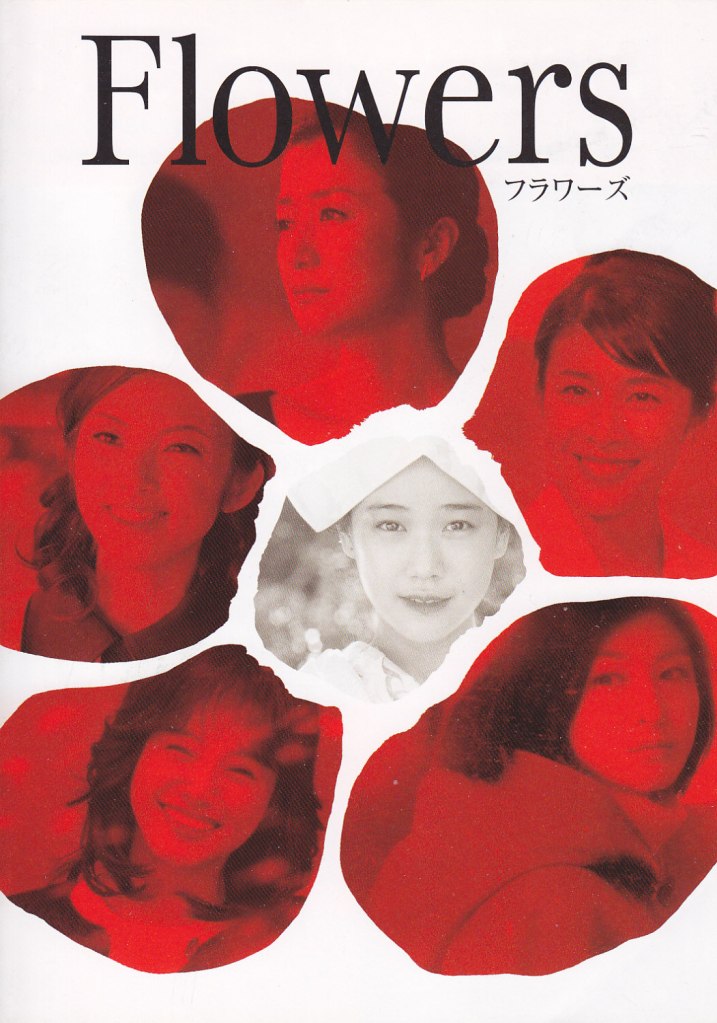

The rate of social change in the second half of the twentieth century was extreme throughout much of the world, but given that Japan had only emerged from centuries of isolation a hundred years before it’s almost as if they were riding their own bullet train into the future. Norihiro Koizumi’s Flowers (フラワーズ) attempts to chart these momentous times through examining the lives of three generations of women, from 1936 to 2009, or through Showa to Heisei, as the choices and responsibilities open to each of them grow and change with new freedoms offered in the post-war world. Or, at least, up to a point.

The rate of social change in the second half of the twentieth century was extreme throughout much of the world, but given that Japan had only emerged from centuries of isolation a hundred years before it’s almost as if they were riding their own bullet train into the future. Norihiro Koizumi’s Flowers (フラワーズ) attempts to chart these momentous times through examining the lives of three generations of women, from 1936 to 2009, or through Showa to Heisei, as the choices and responsibilities open to each of them grow and change with new freedoms offered in the post-war world. Or, at least, up to a point. Times change, and men must change with them or they must die. When Japan was forced to open up to the rest of the world after centuries of isolation, its ancient order of samurai with their feudal lords and subjugated peasantry was abandoned in favour of a more Western looking democratic solution to social stratification. Suddenly the entirety of a man’s life was rendered nil – no more lords to serve, a man must his make his own way now. However, for some, old wounds continue to fester, making it impossible for them to embrace this entirely new way of thinking.

Times change, and men must change with them or they must die. When Japan was forced to open up to the rest of the world after centuries of isolation, its ancient order of samurai with their feudal lords and subjugated peasantry was abandoned in favour of a more Western looking democratic solution to social stratification. Suddenly the entirety of a man’s life was rendered nil – no more lords to serve, a man must his make his own way now. However, for some, old wounds continue to fester, making it impossible for them to embrace this entirely new way of thinking. 2009 marked the centenary year of Osamu Dazai, a hugely important figure in the history of Japanese literature who is known for his melancholic stories of depressed, suicidal and drunken young men in contemporary post-war Japan. Villon’s Wife (ヴィヨンの妻 〜桜桃とタンポポ, Villon no Tsuma: Oto to Tampopo) is a semi-autobiographical look at a wife’s devotion to her husband who causes her nothing but suffering thanks to his intense insecurity and seeming desire for death coupled with an inability to successfully commit suicide.

2009 marked the centenary year of Osamu Dazai, a hugely important figure in the history of Japanese literature who is known for his melancholic stories of depressed, suicidal and drunken young men in contemporary post-war Japan. Villon’s Wife (ヴィヨンの妻 〜桜桃とタンポポ, Villon no Tsuma: Oto to Tampopo) is a semi-autobiographical look at a wife’s devotion to her husband who causes her nothing but suffering thanks to his intense insecurity and seeming desire for death coupled with an inability to successfully commit suicide. The late Ken Takakura is best remembered as cinema’s original hard man but when the occasion arose he could provoke the odd tear or two just the same. 1999’s Poppoya (鉄道員) directed by frequent collaborator Yasuo Furuhata sees him once again playing the tough guy with a battered heart only this time he’s an ageing station master of a small town in deepest snow country which was once a prosperous mining village but is now a rural backwater.

The late Ken Takakura is best remembered as cinema’s original hard man but when the occasion arose he could provoke the odd tear or two just the same. 1999’s Poppoya (鉄道員) directed by frequent collaborator Yasuo Furuhata sees him once again playing the tough guy with a battered heart only this time he’s an ageing station master of a small town in deepest snow country which was once a prosperous mining village but is now a rural backwater.