By 1941 it was becoming harder to make films which were strictly apolitical, though many directors were able to circumvent the constraints of a tightening censorship regime in focusing on the kinds of messages they could get behind. Hiroshi Shimizu’s 1941 drama Record of a Woman Doctor (女医の記録, Joi no Kiroku) is in essence a public information film hoping to foster better hygiene practices in rural areas while encouraging those who might have felt mistrust towards modern medical professionals that they need have no fear of doctors, but in its own way presents a challenge to the militarist line in implying that the humanist teacher and female doctor of the title are in a sense “re-educated” though their exposure to the rural poor.

As the film opens, a collection of medical students from Tokyo Women’s Medical University is sent to a small rural village as part of a pop-up free clinic in an area which otherwise has little access to professional healthcare. As the school teacher, Kamiya (Shin Saburi), who is their liaison explains, the the major health problems faced by the villagers are largely those of poverty, i.e. malnutrition, while infant mortality remains high. Each of these is compounded by the contemporary economic and social realities in that the young often leave to work in cities and then bring back with them urban diseases such as tuberculosis to which the locals are especially vulnerable while in the absence of a professional doctor medical emergencies such as appendicitis or complications with childbirth which might be easily treated are often fatal.

Even so, the villagers are not initially grateful for the doctors’ arrival for various interconnecting reasons. The first is obviously their poverty, not realising that the clinic is free and assuming they cannot afford to take advantage of it. Secondly, they have experience of being ripped off by duplicitous conmen calling themselves doctors and fear that they will simply incur a large debt to be paid at a later date, wary that though the consultation may be free the treatment may not be, the doctor suddenly discovering they are actually incredibly ill and must part with a lot of money in order to redeem their health. The third reason, meanwhile, is older still in the intense stigma surrounding sickness and particularly any respiratory condition.

These are all the attitudes the doctors and the film intend to challenge in insisting that modern medicine is both safe and responsible, interested only in helping prevent the onset of sickness rather needlessly meddling in their way of life. All from the city, the conditions in this small mountain village necessarily shock the doctors noting that the villagers have no culture of regular bathing, often wear the same clothes day and night for indefinite amounts of time with no washing, never air their futons, and live in dark and poorly ventilated homes. The authorities have often recommended felling a thick circle of trees which surrounds the village to let more light in and allow the breeze to travel through though the villagers have always refused.

The felling of the trees takes on a symbolic association of freeing the village from primitive superstition, literally enlightening it, as they shift closer towards modernity in learning the importance of proper sanitation. In a sense these ordinary rural people are being patronised, even sympathetic teacher Kamiya describing them as “culturally deprived” while later implying that he himself has been reformed by their simple way of life. Kamiya’s life is certainly not easy, effectively acting as something like a village headman called in to deal with any sort of local problem while often providing childcare to the infants brought in by his pupils who are supposed to be minding their siblings while the parents work in the fields but are not always completely responsible. Earnest doctor Natsuki (Kinuyo Tanaka) is later much the same, touched by the plight of a local girl suffering with TB kept like a secret in the back room by her mother after being sent back from her factory job. The mother is intent on sending the younger sister in her place even though she too is in poor health because the family is without a male earner and unable to support itself.

The fact that the doctors are all female may in itself be somewhat progressive but also speaks of the times, the male medical students presumably diverted to the military ironically reinforcing the idea that “domestic” concerns are women’s concerns, something echoed in the film’s concluding scenes which see Natsuki, a qualified doctor, operating a daycare centre taking care of local infants while Kamiya runs a callisthenics session behind her. Conversely, it’s also implied that Natsuki must give up her womanhood or any sense of personal desire in order to dedicate herself to the village making it quite clear that there is no possibility of a romantic connection with Kamiya. Even so, the secondary message seems to be that the key to inspiring confidence lies in a process of mutual understanding, Natsuki belatedly realising she’s accidentally alienated some of the local children by usurping their position as caregivers to Kamiya, less relieving them of a burden than firing them from a job they were proud to do while the only real way to gain the villagers’ trust is to listen to their concerns and show them they really do care about their welfare. The subtext may be that their health is important because healthy bodies are needed to fuel the war effort, but even so you can’t argue with the humanist message even as Shimizu’s subversive implication that one can learn alot from the simple way of life cuts against the militarist grain.

Yasujiro Shimazu had been a pioneer of the “shomingeki” – naturalistic stories of ordinary lower middle class life, and his early career included several forays into the world of the “tendency film” which carried strong left-wing messages. By the late 1930s however his films have shifted upwards a little and often deal with the lives of the upper middle classes as they find themselves at another moment of transition during the turbulent militarist years. In contrast with many contemporary films, Shimazu’s may seem curiously apolitical but speak volumes solely through their subtlety and direct refusal to engage with the propagandist concerns of the ruling regime.

Yasujiro Shimazu had been a pioneer of the “shomingeki” – naturalistic stories of ordinary lower middle class life, and his early career included several forays into the world of the “tendency film” which carried strong left-wing messages. By the late 1930s however his films have shifted upwards a little and often deal with the lives of the upper middle classes as they find themselves at another moment of transition during the turbulent militarist years. In contrast with many contemporary films, Shimazu’s may seem curiously apolitical but speak volumes solely through their subtlety and direct refusal to engage with the propagandist concerns of the ruling regime.

Despite being at the forefront of early Japanese cinema, directing Japan’s very first talkie, Heinosuke Gosho remains largely unknown overseas. Like many films of the era, much of Gosho’s silent work is lost but the director was among the pioneers of the “shomin-geki” genre which dealt with ordinary, lower middle class society in contemporary Japan. Burden of Life (人生のお荷物, Jinsei no Onimotsu) is another in the long line of girls getting married movies, but Gosho allows his particular brand of irrevent, ironic humour to colour the scene as an ageing patriarch muses on retiring from the fathering business before resentfully remembering his only son, born to him when he was already 50 years old.

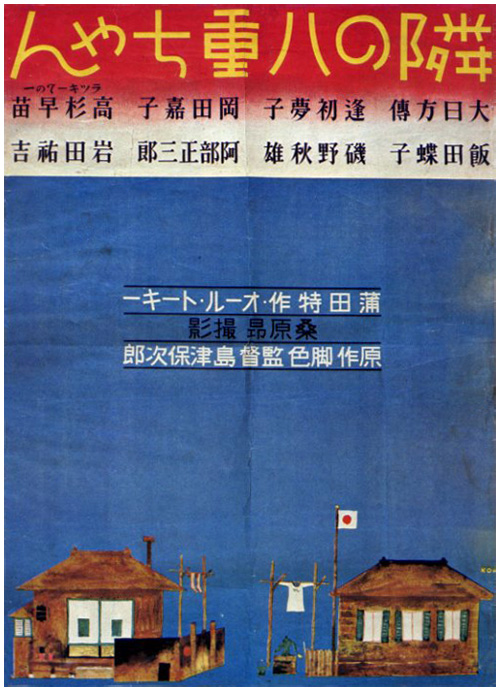

Despite being at the forefront of early Japanese cinema, directing Japan’s very first talkie, Heinosuke Gosho remains largely unknown overseas. Like many films of the era, much of Gosho’s silent work is lost but the director was among the pioneers of the “shomin-geki” genre which dealt with ordinary, lower middle class society in contemporary Japan. Burden of Life (人生のお荷物, Jinsei no Onimotsu) is another in the long line of girls getting married movies, but Gosho allows his particular brand of irrevent, ironic humour to colour the scene as an ageing patriarch muses on retiring from the fathering business before resentfully remembering his only son, born to him when he was already 50 years old. Hiroshi Shimizu is best remembered for his socially conscious, nuanced character pieces often featuring sympathetic portraits of childhood or the suffering of those who find themselves at the mercy of society’s various prejudices. Nevertheless, as a young director at Shochiku, he too had to cut his teeth on a number of program pictures and this two part novel adaptation is among his earliest. Set in a broadly upper middle class milieu, Seven Seas (七つの海, Nanatsu no Umi) is, perhaps, closer to his real life than many of his subsequent efforts but notably makes class itself a matter for discussion as its wealthy elites wield their privilege like a weapon.

Hiroshi Shimizu is best remembered for his socially conscious, nuanced character pieces often featuring sympathetic portraits of childhood or the suffering of those who find themselves at the mercy of society’s various prejudices. Nevertheless, as a young director at Shochiku, he too had to cut his teeth on a number of program pictures and this two part novel adaptation is among his earliest. Set in a broadly upper middle class milieu, Seven Seas (七つの海, Nanatsu no Umi) is, perhaps, closer to his real life than many of his subsequent efforts but notably makes class itself a matter for discussion as its wealthy elites wield their privilege like a weapon.