Post-war desperation drives a collection of otherwise honest men and women towards a criminal act that for all its politeness they are ill-equipped to live with in Kaneto Shindo’s biting social drama The Wolves (狼, Okami). “Wolves” is what the criminals are branded, but the title hints more at the wolfish society which threatens to swallow them whole. After all, it’s eat or be eaten in this dog eat dog world, at least according to a cynical insurance salesman hellbent on exploiting those without means.

Each of the five “criminals” is an employee at Toyo Insurance where they’re immediately pitted against each other, reminded that in order to qualify for a full-time position they need to meet their quotas for six months. The orientation meeting is cultilke in its intensity, the boss insisting that only in insurance can you become a self-made man while recounting his own epiphany as to the worthiness of his profession. They are told that the only two things they need are “faith and honesty”, and then “faith and pursuasion”, while encouraged to think of their work as an act of “worship”, “for the salvation of everyone”.

Yet they’re also told to exploit their friends and family by pressuring them into taking out life insurance policies in order to help them meet their quotas. As one man points out, friends and relatives of the poor are likely to be poor themselves, but these are exactly the kind of people they’re expected to target. They’re told there’s no point going after the weathly because they’re already insured, but there’s something doubly insidious in trying to coax desperate people who can’t quite afford to feed themselves into paying out money they don’t have on the promise of protecting their families from ruin. One man even asks if the policy covers suicide and is told it does if you pay in for a year, sighing that he doesn’t want to wait that long.

“Suicide or robbery, choose one,” one of the salespeople reflects after failing to make their quota once again. They each have reasons to be desperate, all of them already excluded from the mainstream society and uncertain how they will find work if the job falls through. Akiko (Nobuko Otowa) is a war widow with a young son who is being bullied at school because of his cleft palate for which he needs an expensive operation. She’s already tried working as a bar hostess but is quiet by nature and found little success with it. Fujibayashi (Sanae Takasugi) is widowed too with two children and five months behind rent for a dingy flat in a bomb damaged slum where the landlord is about to turn off her electric. Harajima (Jun Hamamura) used to work in a bank but was fired for joining a union and is trapped in a toxic marriage to woman looking for material comfort he can’t offer. Mikawa (Taiji Tonoyama) too is resented by his wife, a former dancer, having lost his factory job to a workplace injury while the ageing Yoshikawa (Ichiro Sugai) was once a famous screenwriter but as he explains people in the film industry turn cold when you’re not hot stuff any more.

Their unlikely descent into crime has its own kind of inevitability in the crushing impossibility of their lives. They may rationalise that what they’re doing is no different from the insurance company that exploits the vulnerable for its own gain, thinking that if they can just get a little ahead they’d be alright while feeling as if robbery and suicide are the only choices left to them and at the end of the day they want to survive. Perhaps you could call them “wolves” for that, but they’re the kind of wolves that give the guards from the cash van they robbed their train fare home after bowing profusely in apology. The real wolves are those like Toyo who think nothing of devouring the weakness of others, promising the poor the future they can’t afford while draining what little they have left out of them. As the film opens, Akiko looks down at a bug writhing in the dirt attacked by ants from all sides and perhaps recognises herself in that image as the sun beats down oppressively on both of them. Breaking into expressionistic storms and unsubtly driving past a US airbase to make clear the source of the decline, Shindo paints a bleak picture of the post-war world as a land of venal wolves which makes criminals of us all.

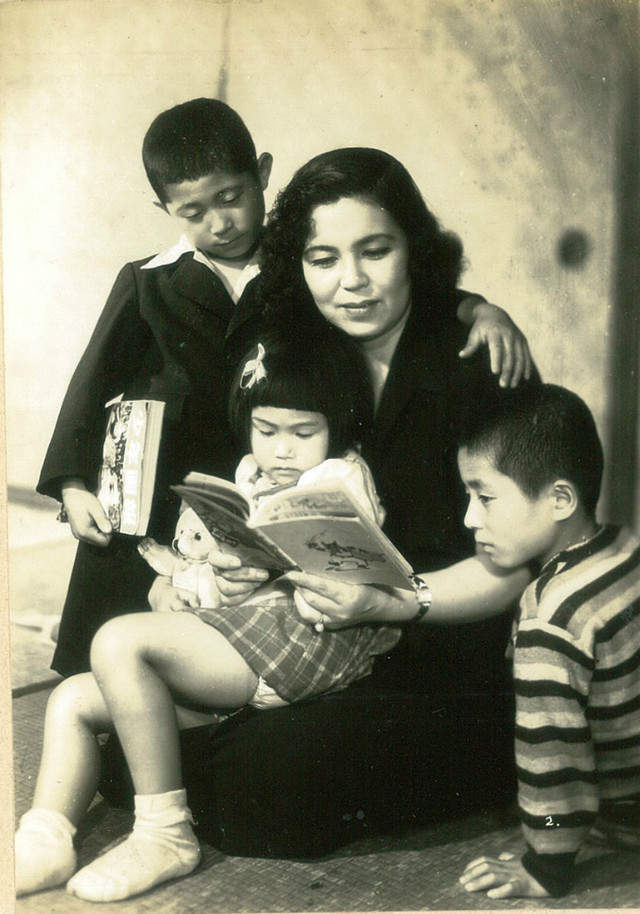

Shimizu’s depression era work was not lacking in down on their luck single mothers forced into difficult positions as they fiercely fought for their children’s future, but 1950’s A Mother’s Love (母情, Bojo) takes an entirely different approach to the problem. Once again Shimizu displays his customary sympathy for all but this particular mother, Toshiko, does not immediately seem to be the self sacrificing embodiment of maternal virtues that the genre usually favours.

Shimizu’s depression era work was not lacking in down on their luck single mothers forced into difficult positions as they fiercely fought for their children’s future, but 1950’s A Mother’s Love (母情, Bojo) takes an entirely different approach to the problem. Once again Shimizu displays his customary sympathy for all but this particular mother, Toshiko, does not immediately seem to be the self sacrificing embodiment of maternal virtues that the genre usually favours.