First it was drugs, then diamonds. This time, it’s gold. Even by this third and final, in the official trilogy at least, instalment in the Sister Street Fighter series, Return of the Sister Street Fighter (帰って来た女必殺拳, Kaette kita onna hissatsu ken) the gangsters still haven’t come up with a good way of smuggling. These ones have hit on the bright idea of dissolving gold in acid and importing it as if it were Chinese liquor.

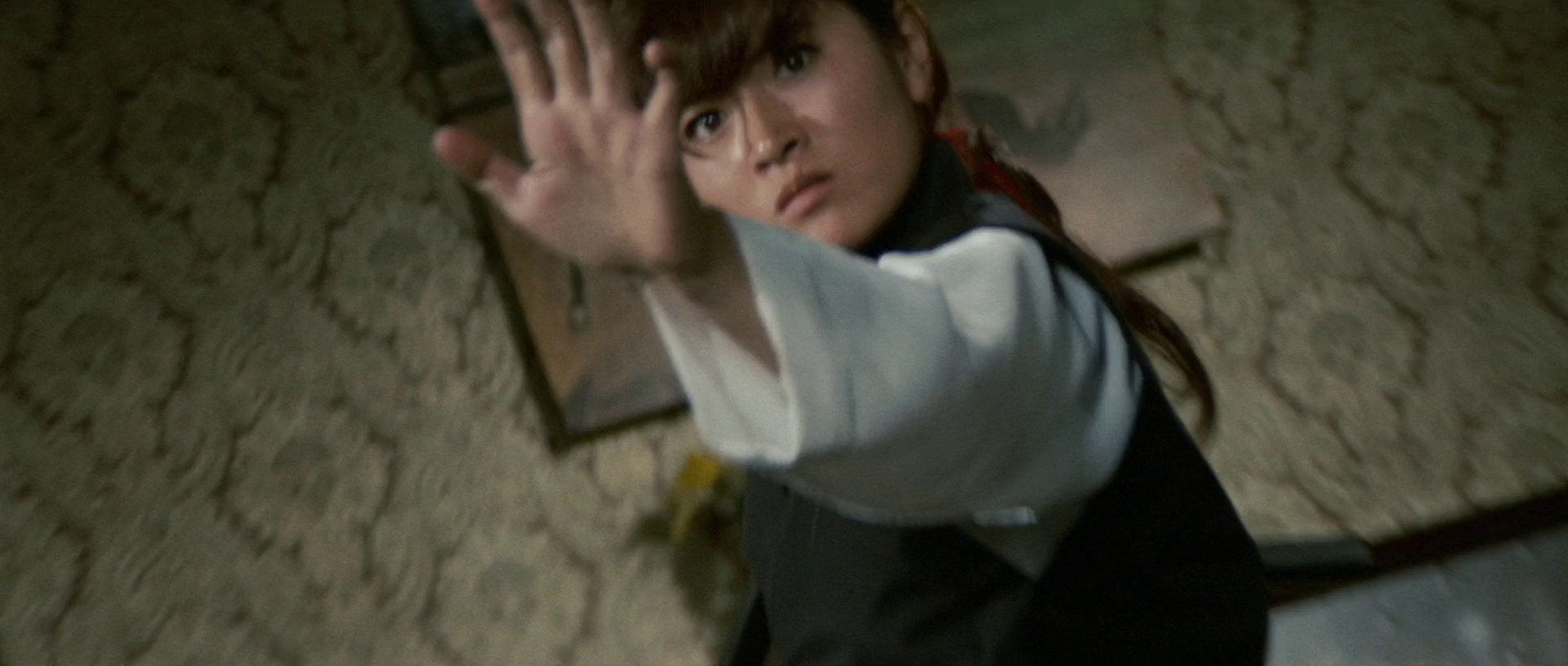

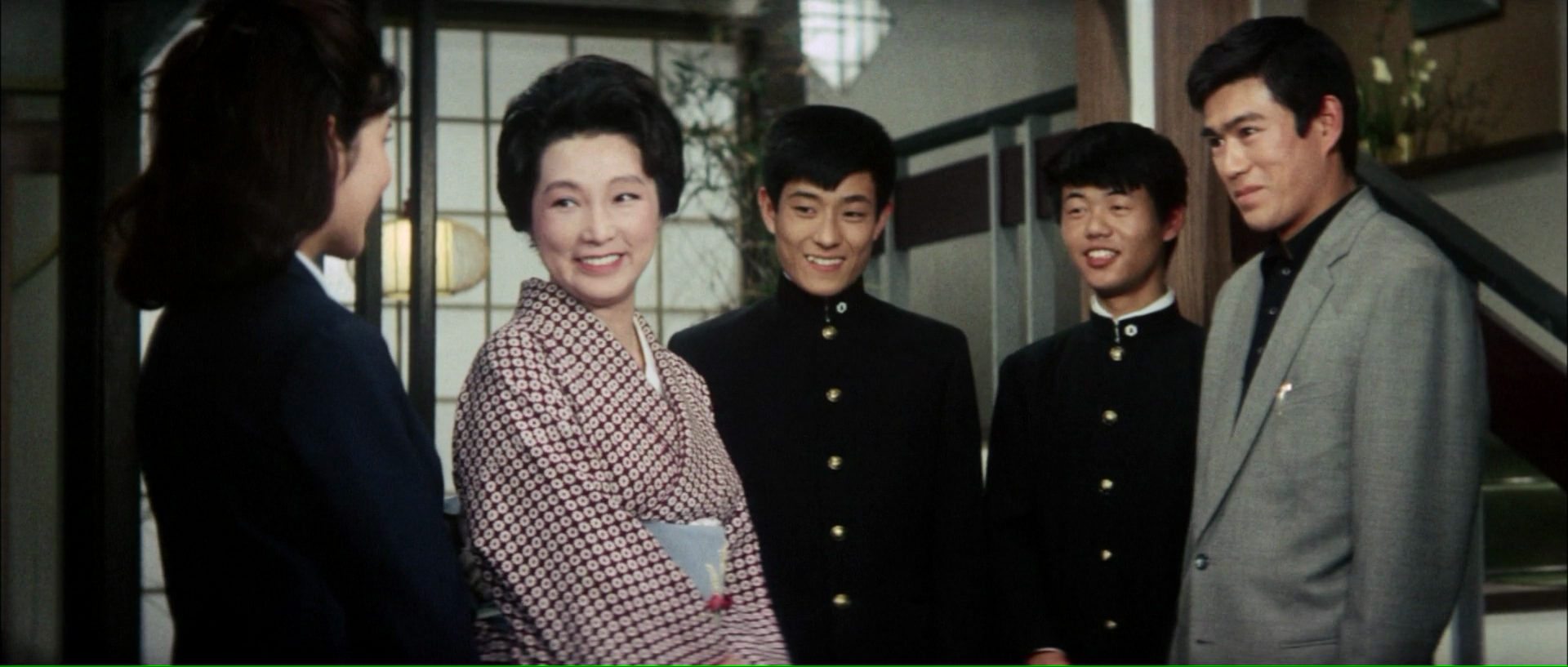

In any case, following the same pattern as the other two films, Return begins in Hong Kong with a friend of Koryu’s (Etsuko Shihomi) being murdered by thugs right after asking her to go to Japan and look for her cousin Shurei (Akane Kawasaki) who has gone missing leaving her little girl Rika (Chieko Onuki) behind. Hoping to track down her sister Reika in Yokohama, Koryu once again heads to Japan with Rika in tow only to discover that Shurei has been forced to become the mistress of the shadow boss of the Yokohama China Town, Oh Ryumei (Rinichi Yamamoto).

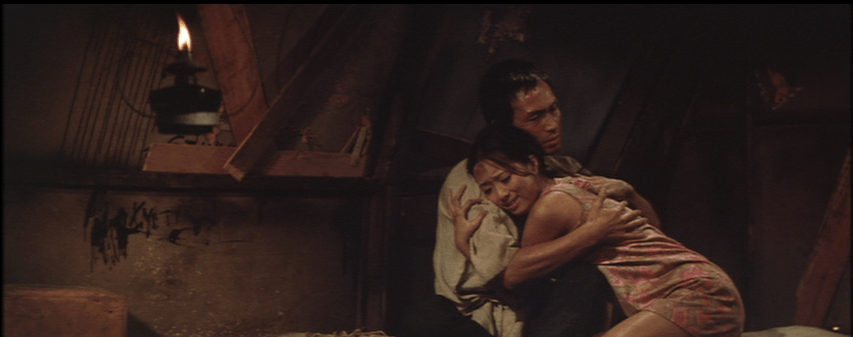

Though the film maybe following a pattern, it’s also, in a sense, diverging in that it, perhaps uncomfortably, attempts shift Koryu into a more maternal space in essentially leaving her responsible for Rika because of all of her other relatives are for one reason or another unavailable. This is, after all, the implication of the closing scenes, that Koryu will be giving up her life of martial arts and fighting crime to look Rika. Even so, as we’ve seen throughout the trilogy, Koryu is not much good at protecting those around her. All of her friends and relatives generally end up dead, leaving the screenwriters having to make up more for the next instalment. Family is a liability for the sisters too, as Shuri and Reika try to save each other from the clutches of Oh, who once again tries to control them with drugs and familial bonds, but ultimately fail.

But then Oh is on a different level even to the admittedly eccentric villains of the first two films. He appears to use a wheelchair and dresses in a stereotypically Chinese outfit (as does Koryu, to be fair). Even his name is obviously Chinese even if uses the Japanese readings of the kanji which literally mean “King Dragon Bright”. Yet when he’s eventually unmasked, it seems that he was actually a member of the Kempeitai, or military police, in Manchuria during the war, where he committed atrocities against the Chinese people and finally stole bunch of gold bullion which has fuelled his post-war Chinatown empire. It’s likely also what sparked his obsession with all things gold. Even his prosthetic hand turns out to be made of it, ironically moulded into a grasping motion.

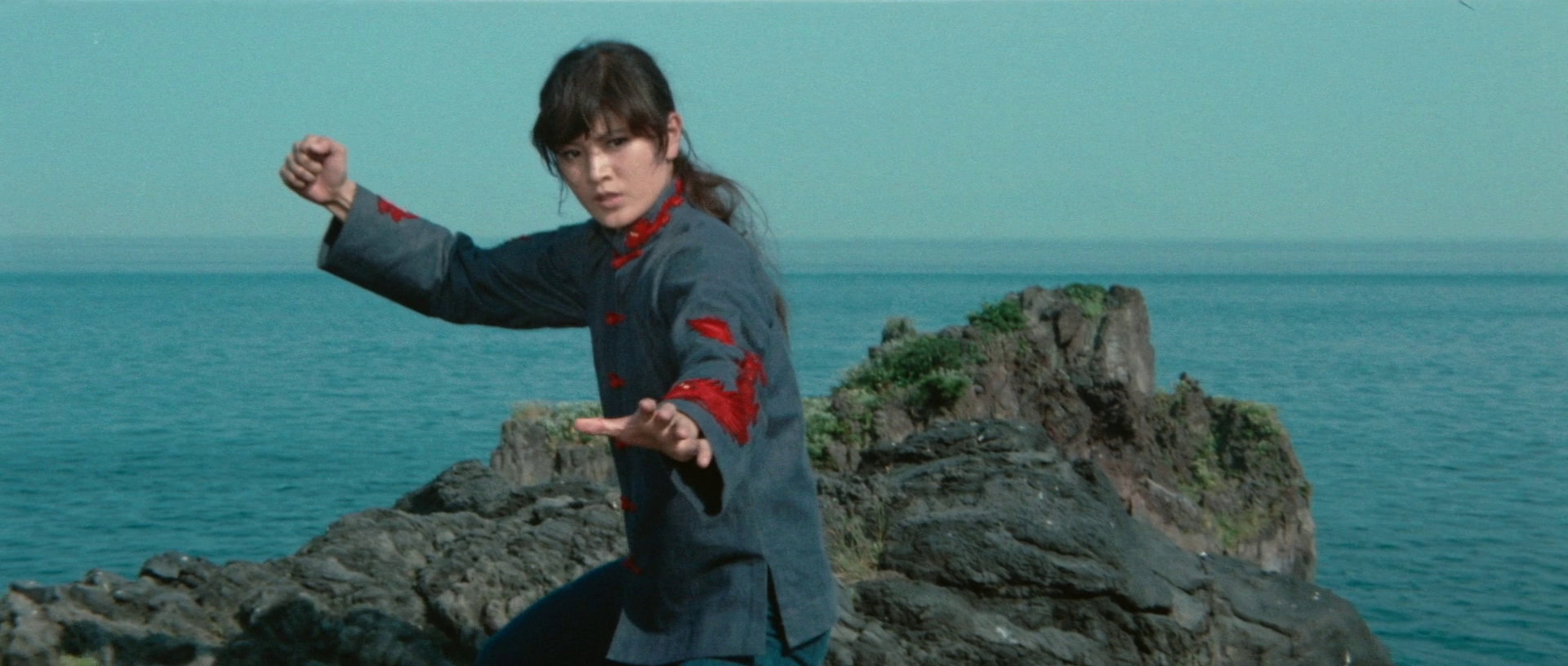

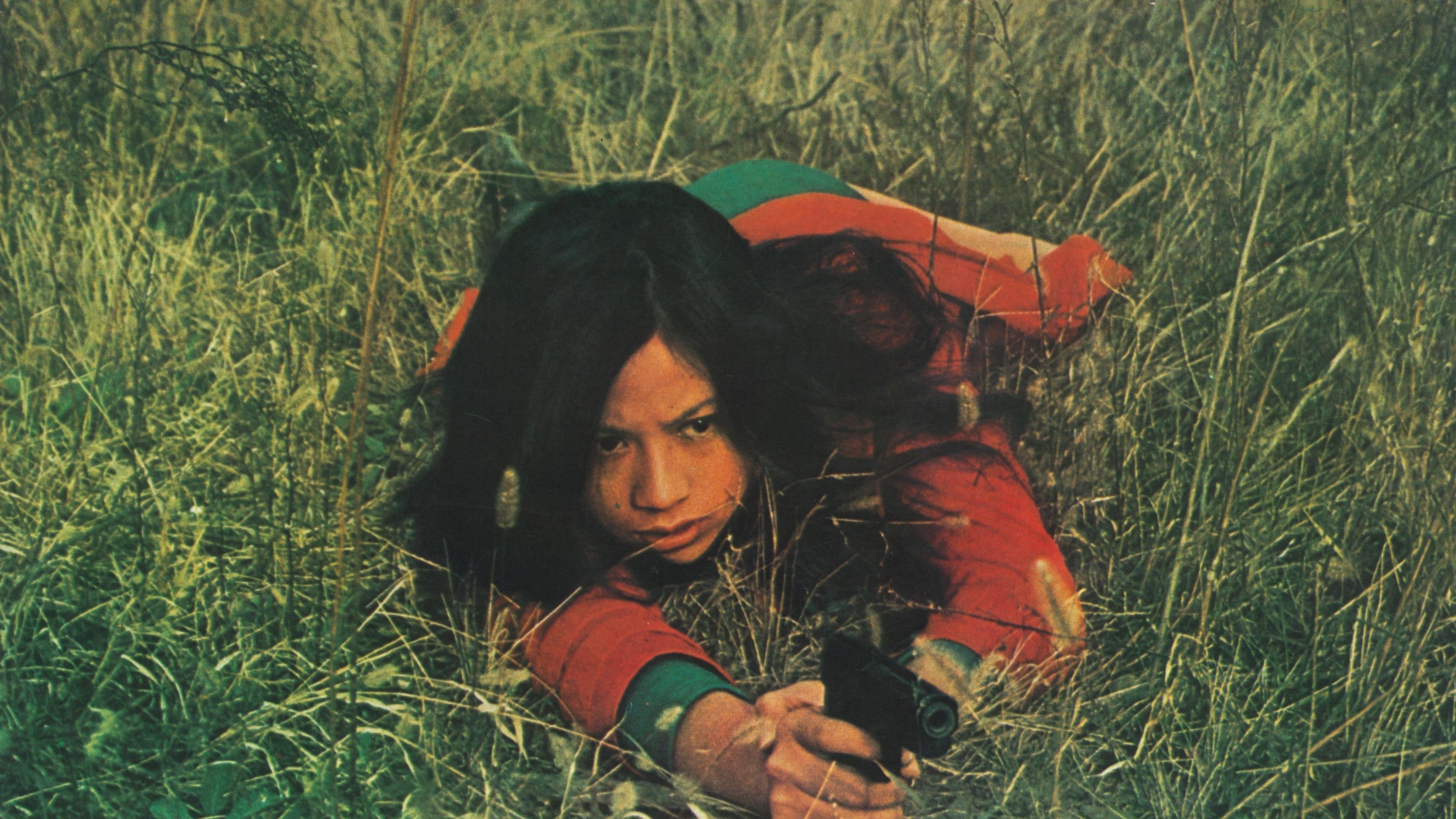

Oh behaves like some kind of Roman Emperor, sitting on his Dias and holding gladiatorial contests to find new henchmen. He declares he that neither capitalism nor communism can beat gold and he’s hedging his bets on both in an ultimate bid for behind-the-scenes power. Embodying the toxic legacy of militarism, he mistakenly underestimates Koryu declaring that that’s what happens to people who depend too much on their physical abilities, thinking her to be dead. His weird henchmen include a man with a lewd-looking and infinitely symbolic snaking sword, but, of course, they’re no match for Koryu who once again discovers an unexpected ally at a critical moment.

Even so, the film’s approach to it’s Chinese themes is very much of its time. Once again, it uses some offensively stereotypical music to introduce the Hong Kong setting, and the friend who went to Japan with Shurei is actually called “Suzie Wong”, as in “The World of”. The world surrounding Oh ought to be quite dark what with the constant presence of acid, the people trafficking, and the weird henchmen but somehow the film maintains its cheerful tone, no doubt bolstered by Koryu’s ability to take the gangsters down, even if her way of doing it isn’t all that efficient and more often than not gets all her friends killed. Nevertheless, this time around it seems she’s fighting for the sisterhood against the evil gangsters who control and abuse women, but even so, her final transition to mother-in-waiting feels a little like a rebuke, as if even little dragons have to cool their fire one day just as her brother in the first instalment had wanted her to settle down and live a “normal life” doing typically feminine things rather than mastering martial arts and shutting down the warped and amoral gangsters currently smuggling their greed and weirdness into a changing Japan.

Trailer (English subtitles)