The hero of Kinji Fukasaku’s Kamikaze Guy (カミカゼ野郎 真昼の決斗, Kamikaze Yaro: Mahiru no Ketto) is described as cheerful and with a spirited personality though unfortunately not very bright. A vehicle for rising star Chiba, the film was intended as the first in a series starring its bumbling hero, Ken Mitarai, though no other instalments were ever produced. In any case, it seems to echo the lighter side of Nikkatsu’s borderless action line along with Toho’s spy spoofs in its wrong man tale of wartime legacy and corporate duplicity.

Often called “Mr. Toilet” because of the way his name is pronounced, Ken (Sonny Chiba) is a slightly sleazy private plane pilot who has pinups on the roof of the cockpit. According to the voiceover, there is no bottom to the depths of his crassness which is a sentiment later borne out by his attempt to pick up a woman on a ski slope by uttering the immortal lines “please don’t think I’m a creep, just hear me out.” However, events take a turn for the strange when the pair of them are witness to a murder. Ken valiantly tries to help, but is later brought in as a suspect himself, partly as the police are annoyed by his smugness. The woman, Koran (Bai Lan), turns out to be from Taiwan which is where Ken ends up flying only to discover that his cargo is the body of an old man he also encountered at the slopes.

In keeping wth the growing internationalism of mid-1960s Japanese cinema, the film travels to Taiwan but does so in a rather complicated way as Ken is drawn into a plot concerning three men responsible for the death of a Japanese official shortly after the war killed because he wanted to return 200 billion yen’s worth of diamonds stolen from the local population. While on his travels, Ken runs into a woman who was trafficked to the island at the age of 15 and later cheated out of the money she’s saved to return. The film almost flirts with the awkward relationship between the two nations and Japan’s imperialist past but in the end does not quite engage with it save for the brief appearance of the indigenous community which seems to stand in for layers of historical and contemporary colonialism.

In any case, the murdered man was Japanese as were the two of the three currently being targeted in the assassination plot Ken is being framed for. Ken’s defining characteristic is his bumbling earnestness in which his determination to get to the bottom of the mystery only lands him in further trouble. At one point he even tries to stop the villain escaping by standing in front of the plane with his arms wide open as if it hadn’t really occurred to him that a man who has already killed a number of people is unlikely to be deterred by the thought of killing one more. Nevertheless, it provides the film with one of its more memorable and quite incredible sequences as Ken grabs on to the wing support as the plane is taking off and eventually climbs his way inside.

Chiba reportedly designed the action sequences himself and his martial arts skills are very definitely on display in the unusually well accomplished fight scenes while the film also contains a lengthy and expertly choreographed car chase albeit one occasionally interrupted by random bison and an indigenous parade. Perhaps because of this manly tone, there is an unfortunate strain of semi-ironic misogyny that runs through the film with frequent exclamations that women are too quick to jump to conclusions while Ken later seems slightly put out that Koran is “using her feminine wiles” to combat the bad guys.

By the same token, there is something a little ironic and subversive in the film’s use of the term kamikaze, self-adopted by Ken to emblematise his devil may care nature while otherwise setting the action in a nation once colonised by Japan that holds a celebratory gala in Ken’s honour for his assistance in retrieving the gold and returning it to the Taiwanese people. Perhaps in another sense, it echoes a new willingness to make restitution with the past even if Ken bumbles his way into it and does so by accident taking on both the new and destructive capitalism of the post-war society and the toxic wartime legacy and freeing himself from them, literally a body flying in midair with no direction but his own.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

All things considered, a live pig is a rather insensitive gift to present to your local police station, though any gift at all might be considered in appropriate even if offered by a well meaning colleague keen to help out when a horrific murder may be connected to his missing person case. By 1977 Kinji Fukasaku had made a name for himself through the wildly successful “jitsuroku” or “true record” genre of yakuza movies kickstarted by his own

All things considered, a live pig is a rather insensitive gift to present to your local police station, though any gift at all might be considered in appropriate even if offered by a well meaning colleague keen to help out when a horrific murder may be connected to his missing person case. By 1977 Kinji Fukasaku had made a name for himself through the wildly successful “jitsuroku” or “true record” genre of yakuza movies kickstarted by his own  Universal’s Monster series might have a lot to answer for in creating a cinematic canon of ambiguous “heroes” who are by turns both worthy of pity and the embodiment of somehow unnatural evil. Despite the enduring popularity of Dracula, Frankenstein (dropping his “monster” monicker and acceding to his master’s name even if not quite his identity), and even The Mummy, the Wolf Man has, appropriately enough, remained a shadowy figure relegated to a substratum of second-rate classics. Kazuhiko Yamaguchi’s Wolf Guy (ウルフガイ 燃えよ狼男, Wolf Guy: Moero Okami Otoko, AKA Wolfguy: Enraged Lycanthrope) is no exception to this rule and in any case pays little more than lip service to werewolf lore. An adaptation of a popular manga, Wolf Guy is one among dozens of disposable B-movies starring action hero Sonny Chiba which have languished in obscurity save for the attentions of dedicated superfans, but sure as a full moon its time has come again.

Universal’s Monster series might have a lot to answer for in creating a cinematic canon of ambiguous “heroes” who are by turns both worthy of pity and the embodiment of somehow unnatural evil. Despite the enduring popularity of Dracula, Frankenstein (dropping his “monster” monicker and acceding to his master’s name even if not quite his identity), and even The Mummy, the Wolf Man has, appropriately enough, remained a shadowy figure relegated to a substratum of second-rate classics. Kazuhiko Yamaguchi’s Wolf Guy (ウルフガイ 燃えよ狼男, Wolf Guy: Moero Okami Otoko, AKA Wolfguy: Enraged Lycanthrope) is no exception to this rule and in any case pays little more than lip service to werewolf lore. An adaptation of a popular manga, Wolf Guy is one among dozens of disposable B-movies starring action hero Sonny Chiba which have languished in obscurity save for the attentions of dedicated superfans, but sure as a full moon its time has come again. For one reason or another, the 1970s gave rise to a wave of disaster movies as Earthquakes devastated cities, high rise buildings caught fire, and ocean liners capsized. Japan wanted in on the action and so set about constructing its own culturally specific crisis movie. The central idea behind The Bullet Train (新幹線大爆破, Shinkansen Daibakuha) may well sound familiar as it was reappropriated for the 1994 smash hit and ongoing pop culture phenomenon Speed, but even if de Bont’s finely tuned rollercoaster was not exactly devoid of subversive political commentary The Bullet Train takes things one step further.

For one reason or another, the 1970s gave rise to a wave of disaster movies as Earthquakes devastated cities, high rise buildings caught fire, and ocean liners capsized. Japan wanted in on the action and so set about constructing its own culturally specific crisis movie. The central idea behind The Bullet Train (新幹線大爆破, Shinkansen Daibakuha) may well sound familiar as it was reappropriated for the 1994 smash hit and ongoing pop culture phenomenon Speed, but even if de Bont’s finely tuned rollercoaster was not exactly devoid of subversive political commentary The Bullet Train takes things one step further. You know how it is. You work hard, make sacrifices and expect the system to reward you with advancement. The system, however, has its biases and none of them are in your favour. Watching the less well equipped leapfrog ahead by virtue of their privileges, it’s difficult not to lose heart. Asakura (Yusaku Matsuda), the (anti) hero of Toru Murakawa’s Resurrection of Golden Wolf (蘇る金狼, Yomigaeru Kinro), has had about all he can take of the dead end accountancy job he’s supposedly lucky to have despite his high school level education (even if it is topped up with night school qualifications). Resentful at the way the odds are always stacked against him, Asakura decides to take his revenge but quickly finds himself becoming embroiled in a series of ongoing corporate scandals.

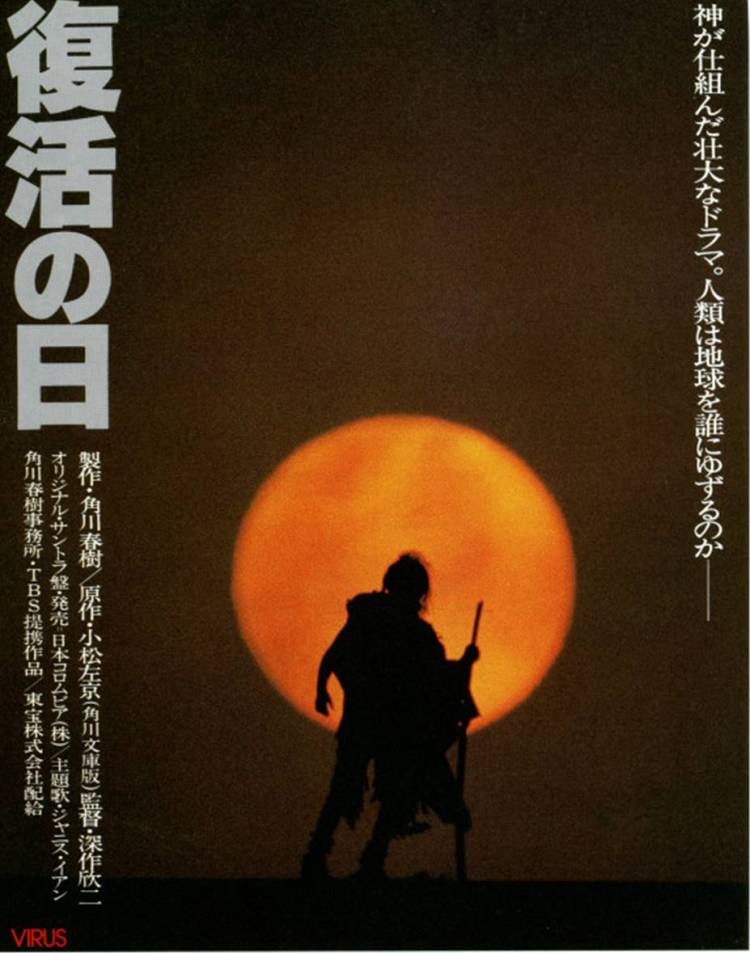

You know how it is. You work hard, make sacrifices and expect the system to reward you with advancement. The system, however, has its biases and none of them are in your favour. Watching the less well equipped leapfrog ahead by virtue of their privileges, it’s difficult not to lose heart. Asakura (Yusaku Matsuda), the (anti) hero of Toru Murakawa’s Resurrection of Golden Wolf (蘇る金狼, Yomigaeru Kinro), has had about all he can take of the dead end accountancy job he’s supposedly lucky to have despite his high school level education (even if it is topped up with night school qualifications). Resentful at the way the odds are always stacked against him, Asakura decides to take his revenge but quickly finds himself becoming embroiled in a series of ongoing corporate scandals. The ‘70s. It was a bleak time when everyone was frightened of everything and desperately needed to be reminded why everything was so terrifying by sitting in a dark room and watching a disaster unfold on-screen. Thank goodness everything is so different now! Being the extraordinarily savvy guy he was, Hiroki Kadokawa decided he could harness this wave of cold war paranoia to make his move into international cinema with the still fledgling film arm he’d added to the publishing company inherited from his father.

The ‘70s. It was a bleak time when everyone was frightened of everything and desperately needed to be reminded why everything was so terrifying by sitting in a dark room and watching a disaster unfold on-screen. Thank goodness everything is so different now! Being the extraordinarily savvy guy he was, Hiroki Kadokawa decided he could harness this wave of cold war paranoia to make his move into international cinema with the still fledgling film arm he’d added to the publishing company inherited from his father.