“If no one denounces the absurdity of this world, then our descendants will keep suffering,” a soon-to-be ronin insists in Eiichi Kudo’s revengers tragedy, Eleven Samurai (十一人の侍, Juichinin no Samurai). It seems clear from the outset that their actions will have little effect no matter whether they succeed or fail because the enemy is feudalism which may be approaching the end of its life but is definitely not dead yet. They can at least attempt to avenge their clan even if they can’t save it while refusing to let an entitled, selfish lord get away doing whatever he likes just because he happens to be the son of the former shogun and brother of the current one.

The opening scenes see Nariatsu (Kantaro Suga) chasing a deer having declared himself a “real hunter”. He ignores the cries of his men to watch where he’s going and sails over the border into the territory of Oshi which amounts to an invasion seeing as he is armed and has no permission to be there. The deer gets away, but Nariatsu shoots an old woodcutter whom he felt to be in his way with his bow and arrow. The Lord of the Abe clan that rules Oshi immediately takes him to task and tells Noriatsu that his behaviour is unbecoming for the son of the former shogun. He’s committed a murder in their territory, but they’re prepared to let it go as long as he leaves as soon as possible. But Nariatsu doesn’t like being told what to do and simply shoots the lord in the eye, potentially sparking a diplomatic incident.

The Abe clan try to lodge a complaint in Edo, but are shut down by courtier Mizuno (Kei Sato) who fears that to acknowledge an event such as this would damage the moral authority of the Tokugawa regime. He decides to cover the whole thing up by claiming it was the Abe clan who insulted Noriatsu. The Abe clan will then be dissolved, and Oshi essentially gets nationalised. All of which suits Nariatsu just fine because he wants to take control of Oshi and expand his territory anyway. Part of his petulance seems to stem from the fact that he feels hard done by with such a small inheritance when his brother became the Shogun and received multiple fiefdoms. The previous Shogun, Tokugawa Ieyoshi, had produced an unusual number of children which became quite a problem in that he had to find lands for them all and eventually hastened the demise of the shogunate because of the additional strain.

But Nariatsu is also an overgrown child who has no idea how to do anything for himself and no concern for the feelings or fortunes of others. When instructed to do something he doesn’t want to, Nariatsu petulantly stamps his feet and complains, and when his actions are challenged he simply replies that he’ll be telling his father. In fact, he is so infuriating that it’s likely most of his men secretly want him dead too, including his chief adviser Gyobu (Ryutaro Otomo) who was once the General Inspector but is now expected to babysit this absolute buffoon. Even though Nariatsu knows the Abe clan will be trying to kill him, he still sneaks out to the red light district and gets blind drunk with geisha which in itself is conduct unbecoming for a high ranking samurai such as himself.

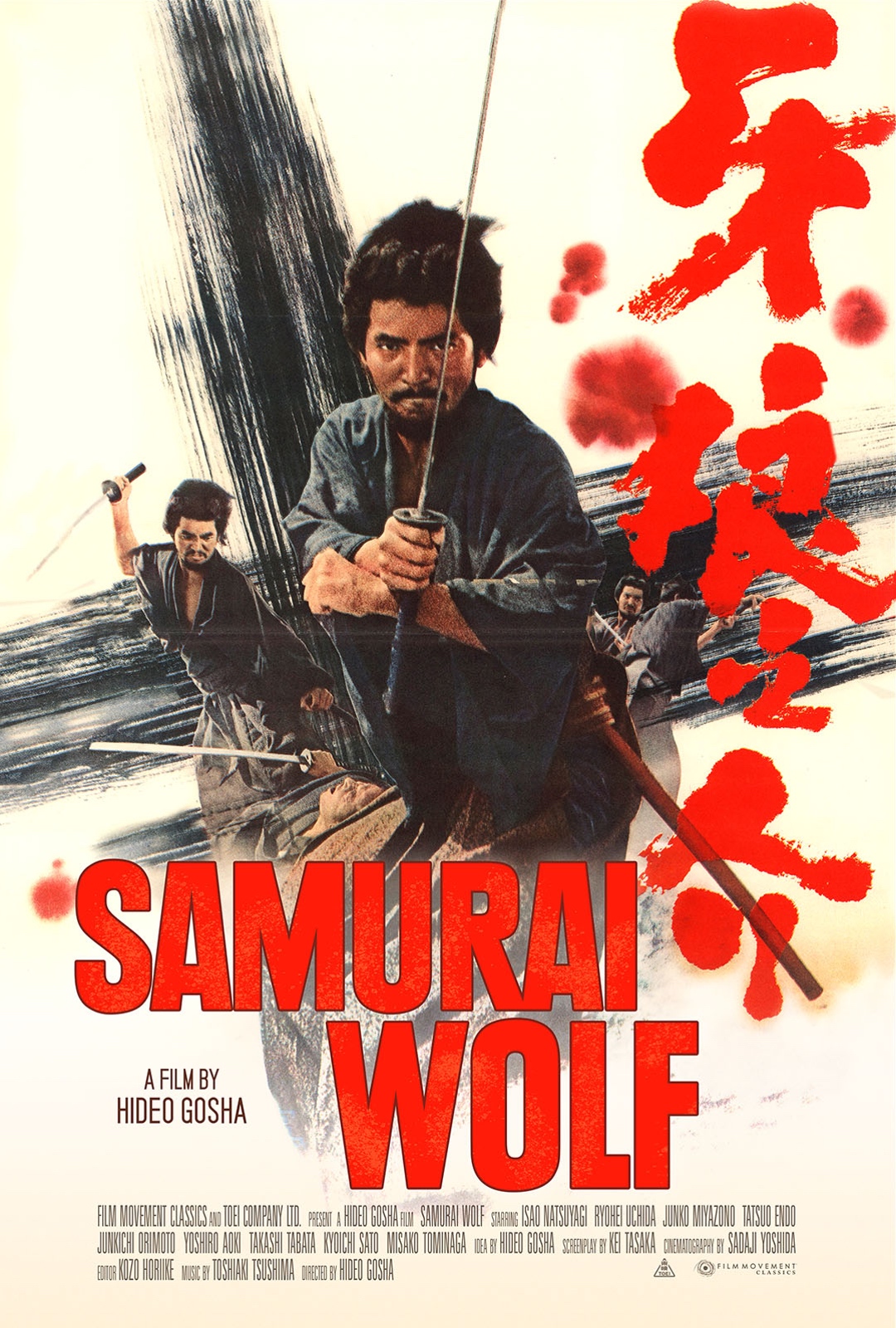

As such, he represents almost everything that’s wrong with the feudal order while Mizuno represents the rest. It’s Mizuno that secretly plots against the plotters, manipulating them into giving up their assassination mission by claiming to have switched sides only to backtrack and reveal he’s actually still working for Nariatsu fearing a reputational loss for the Tokugawa. Chief revenger Hayato (Isao Natsuyagi) is also banking on this fear of reputational damage, certain that the Shogunate won’t be able to bear the humiliation of Nariastsu being killed by a ronin so will instead claim that he died from an illness. Vowing to avenge the clan, Hayato righteously gives up his position to become one so that the Abes won’t be linked to the crime and is joined by 10 more similarly annoyed samurai. Six of them are already “dead” having been asked to commit seppuku for recklessly attacking Nariatsu on their own and blowing the whole operation.

Hayato at least believes this to be a suicide mission. He leaves his loving wife and home and allows people to think he’s run off with Nui (Eiko Okawa), the younger sister of one of their number who died before he could join them. They do this because they think it must be done, and also because if no one stands up to samurai oppression it will never end. Wandering peasant Daijuro (Ko Nishimura) agrees with them. He wants revenge on the samurai for raping his sister after which his father and brother took their own lives. Nariatsu is as good as anyone else and he does very much need to die.

But despite Daijuro’s homemade cannons, nothing quite goes to plan. Kudo sets his final battle in an atmospheric, misty valley that is an obvious stand in for the underworld. Hayato may succeed in killing Nariatsu but it’s a pyrrhic victory. Though he vowed “to put an end to this ridiculous world,” a samurai cannot really win this battle. It’s Daijuro who eventually walks off with Nariatsu’s head, symbolically decapitating the shogunate which the closing titles confirm was mortally wounded by this incident. With his striking black and white cinematography, Kudo does indeed paint this samurai world as a hellish place ruled over by an infinitely corrupt and self-interested authority. The nihilistic futility of it all is emphasised by the figure of a grown man sitting like a small child and splashing his sword in a puddle while surrounded by dead bodies. There might be a way out of this, but not for the samurai, only for those who will come after and perhaps finally be free of this world’s absurdity.