Something of an oddity, Tetsuya Yamanouchi’s The Magic Serpent (怪竜大決戦, Kairyu daikessen) puts a tokusatsu spin on the classic ninja movie in a jidaigeki tale of revenge that ends ultimately in revolution rather than the restoration of the feudal order. A big screen monster movie from Toei, the film was released around the same time as the studio embarked on its signature line of tokusatsu serials such as Captain Ultra which aired the following year.

Drawing inspiration from the Tale of Jiraiya, the hero Ikazuchimaru (Hiroki Matsukata) later even giving himself Jiraiya’s name and indeed riding a giant toad, The Magic Serpent nevertheless seems to have been influenced by contemporary wuxia films from Hong Kong and Taiwan right down to the appearance of martial arts master with a flowing white beard and a distinctly philosophical way of speaking. At one point, Ikazuchimaru even rides an animated cloud much like the Monkey King in Journey to the West.

In any case, set in the pre-Edo feudal era the revenge tale revolves around treacherous lords as the ambitious Yuki Daijo (Bin Amatsu) teams up with evil ninja Orochimaru (Ryutaro Otomo) to kill his master, Ogata, and take over his castle. Daijo orders that Ogata’s son, Ikazuchimaru, be murdered so that he won’t cause them any problems in the future but the boy is rescued by a servant and makes his escape at which point Orochimaru transforms into a giant dragon and capsizes his boat. Luckily, a giant bird then arrives and pecks Orochimaru on the nose, rescuing Ikazuchimaru and taking him to the mountain retreat of ninja master Goma Douji (Nobuo Kaneko) where he trains for 14 years in preparation for his revenge.

To this point, it might be said that the corruption is to the feudal era rather than of it though through his travels Ikazuchimaru comes to see how the ordinary people suffer as a result of Yuki Daijo’s oppressive rule. He comes to the rescue of a small family who in turn help him to overcome Yuki Daijo’s checkpoints as they search for him having become aware that he has survived and is intent on his revenge. But unbeknownst to him, Orochimaru is also potting to exploit the threat posed by Ikazuchimaru by stealing his identity to oust Yuki Daijo and take over the castle himself as its “rightful” heir.

Meanwhile, Ichikazu meets his opposite number, Tsunade (Tomoko Ogawa), who is searching for a father she has never met and can identify only by a keepsake from her now departed mother. In a shocking turn of events, it transpires that her grandmother is also a ninja master and gives her a magic hairpin she can use to call for help. Both searching for their birthright, the two eventually wind up at the castle and a confrontation with a corrupted feudalism. The surprising thing is in this case that Ikazuchimaru rejects his place as the heir and declines to rebuild the clan. With the castle now destroyed by the fight between his giant toad, Ochimaru’s dragon, and a mystery third party, the feudal order itself has been ruined. “There are only beautiful fields for you farmers left to create,” he tells the surviving members of the family that helped him. “Stay healthy and cultivate great lands.” He leaves with Tsunade, who is returning to her grandmother, and vows to travel to the place where his master lies or symbolically to the place of his spiritual rather than biological father.

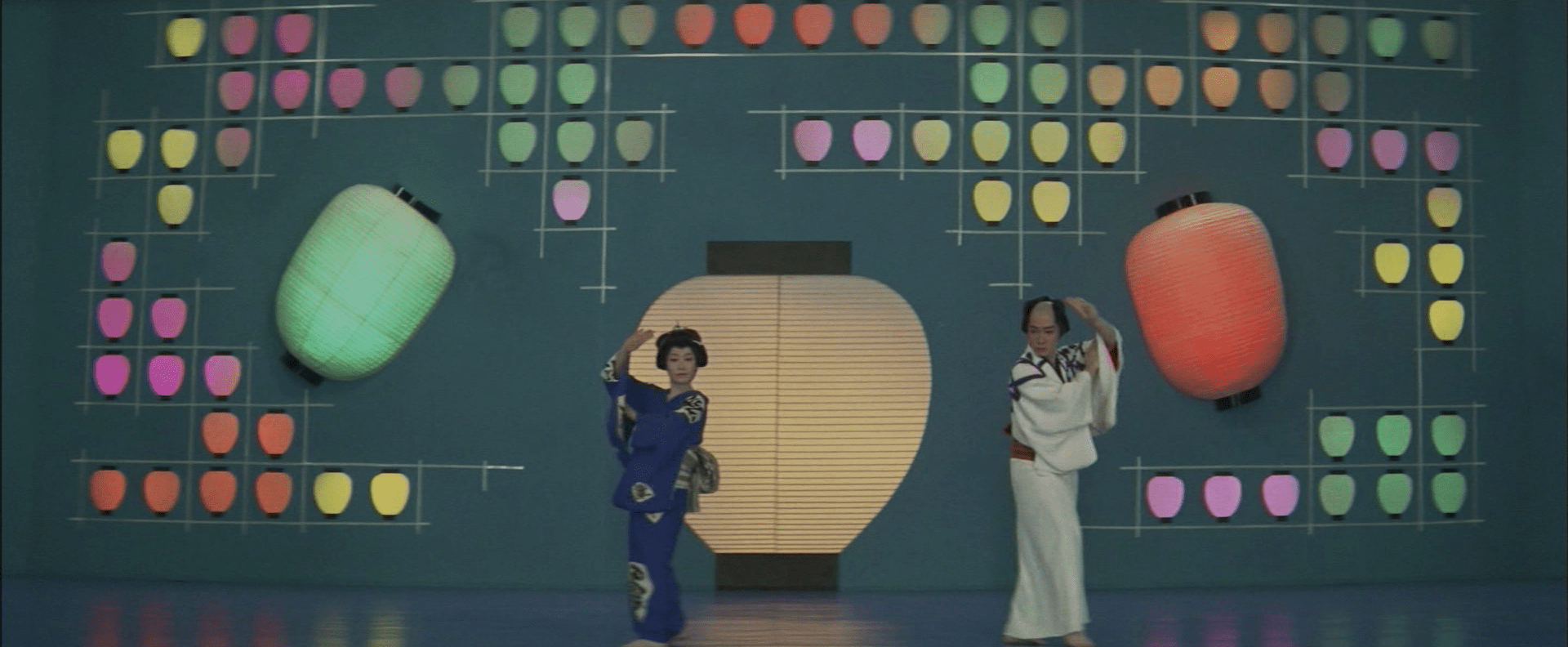

Yamanouchi went on to work more in television than movies, apparently a devotee of period drama in both his personal and professional lives yet, makes fantastic use of special effects on an otherwise limited budget even briefly switching to black and white when the ghosts of Ikazuchimaru’s murdered parents appear to torment the usurping Yuki Daijo. Thunder, lightning, and ninja tricks mix seamlessly with tokusatsu action as the giant monsters finally approach their showdown yet perhaps in keeping with the surprisingly progressive outcome Ikazuchimaru struggles against the evil powers of Orochimaru and in the end cannot win alone but only with the help of those around him as they rise to challenge not only Orochimaru’s evil subversion of morals both feudal and spiritual in his betrayal of his master, but the evils of the feudal order itself and finally free themselves from its oppressive yoke.