The Japanese film industry is generally regarded as fairly insular and focused solely on the domestic market with half an eye on other Asian territories where its stars are already popular. It has, however, made some attempts to enter Hollywood particularly in the 1970s with films such as Kinji Fukasaku’s Virus which for various reasons was largely unsuccessful in either market and suffered artistically from its attempts to bend itself to an international audience.

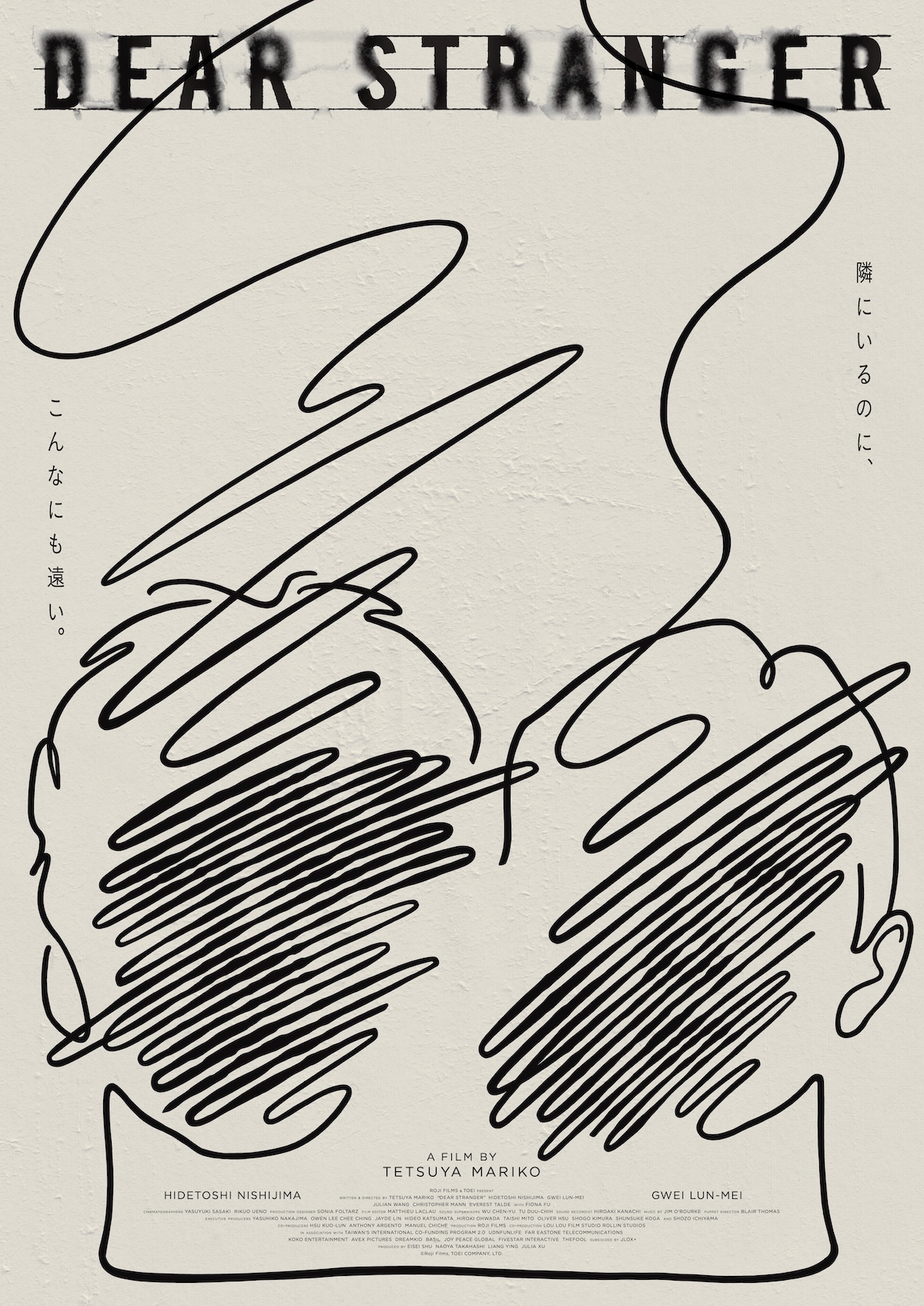

Tetsuya Mariko’s Dear Stranger (ディア・ストレンジャー) is the first in Toei’s contemporary attempt to court an audience outside of Japan as part of its Toei New Wave 2033 initiative, but it seems to be suffering from some of the same problems. The biggest is that 90% of the film is in English but the delivery is often stilted and inauthentic from both the international and native-speaking cast. That may in one way be ironic, as one of the major themes is the impossibility of communication. Emotional clarity is only really revealed during the puppetry sequences when no dialogue is involved. Set in New York, the film shifts between Mandarin, Japanese, Spanish, English and sign language, but simultaneously suggests the problem is less an external language barrier than an internal one that prevents people from saying what they really mean or encourages them to keep the truth of themselves hidden.

It’s living in this liminal third space that disrupts the marriage between Taiwanese-American Jane / Yi-zhen (Gwei Lun-mei) and her Japanese husband Kenji (Hidetoshi Nishijima) as she points out that they speak to each other in a language is not their own. At moments of high tension, they argue in Mandarin and Japanese, though as we largely discover there are more issues in play, beginning with the fact that their marriage may at least partially have begun as one of convenience. Kenji is not the biological father of their young son Kai. Jane finds herself asking who they are as a couple without him and if she ever really loved Kenji at all. Kenji suggests he married her because he loved her and accepted the child as his own for the same reason, but throughout the film is in an incredibly angry and hostile mood. He appears at times sexist, criticising Jane for not keeping the house tidy while he is “under a lot of pressure” at work and resents “the chaos” of their life. Jane’s mother doesn’t approve of her working either and calls her a bad mother for doing so even while expecting her to mind their convenience while she tries to find a carer to look after her father who is living with advanced dementia and can’t be left alone.

Part of that is likely that they need someone who speaks Mandarin, hinting at the sense of isolation and orphanhood that comes with migration in lacking extended familial support that in this case does not seem to be met by community. Jane too feels isolated and trapped by her role as a mother. She expresses herself only through her puppetry, which is also something denied her by Kenji and her mother. Kenji, meanwhile, feels undervalued at the university where his supervisor seems dismissive of him and his work which he regards as unoriginal. He may have decided to marry Jane in part in search of family having lost of his own in Japan with his mother never having been found after the Kobe earthquake when when he was a teenager, but simultaneously struggles to integrate himself within their family. His loss of Kai who disappears while he was supposed to be taking care of him is then symbolic in reflecting his own frustrated paternity and fear that the biological father will return to take all this away from him.

In many ways, it’s Kenji’s own psyche that’s in ruins informing his academic practice which focuses on abandoned and disused buildings and the effect they have on the surrounding environment. He’s asking himself how to create a new world from the ashes of the old, but doesn’t appear to have done so successfully in his own life and is increasingly unsure if he wants to. Perhaps because of its awkwardness, the film takes on an increasingly surreal quality as Kenji is heckled by irrationally angry guests at his book presentation and basically accused of facilitating urban crime in his praise of disused spaces and then descends into some kind of fugue state chasing the larger-than-life puppet version of Kai from Jane’s play which is also an embodiment of her own frustrated yearning for freedom.

“In the wreckage we find truth,” Kenji answers one of the questioners at his presentation and it may in a sense be true for him but in another perhaps not. It becomes unclear what exactly he experiences as “real” and what not, what a product of his own mythologising and what actually happened, while Jane slips quietly into the background and her sudden acceptance of Kenji whom she previously regarded as “unreliable” and appeared to resent, seems somewhat hollow given that he continues to treat her coldly and is extremely hostile with all around him from the police, who are actually trying to help find his son, to the well-meaning kindergarten teachers, and his employers. In the end, it’s really Kenji who is stranger to himself much more than a stranger in a strange land trying to forge a new identity in a place of psychological ruin.

Dear Stranger was screened as part of this year’s Busan International Film Festival

Trailer (English subtitles)

Post-golden age, Japanese cinema has arguably had a preoccupation with the angry young man. From the ever present tension of the seishun eiga to the frustrations of ‘70s art films and the punk nihilism of the 1980s which only seemed to deepen after the bubble burst, the young men of Japanese cinema have most often gone to war with themselves in violent intensity, prepared to burn the world which they feel holds no place for them. Tetsuya Mariko’s Destruction Babies (ディストラクション・ベイビーズ) is a fine addition to this tradition but also an urgent one. Stepping somehow beyond nihilism, Mariko’s vision of his country’s future is a bleak one in which young, fatherless men inherit the traditions of their ancestors all the while desperately trying to destroy them. Devoid of hope, of purpose, and of human connection the youth of the day get their kicks vicariously, so busy sharing their experiences online that reality has become an obsolete concept and the physical sensation of violence the only remaining truth.

Post-golden age, Japanese cinema has arguably had a preoccupation with the angry young man. From the ever present tension of the seishun eiga to the frustrations of ‘70s art films and the punk nihilism of the 1980s which only seemed to deepen after the bubble burst, the young men of Japanese cinema have most often gone to war with themselves in violent intensity, prepared to burn the world which they feel holds no place for them. Tetsuya Mariko’s Destruction Babies (ディストラクション・ベイビーズ) is a fine addition to this tradition but also an urgent one. Stepping somehow beyond nihilism, Mariko’s vision of his country’s future is a bleak one in which young, fatherless men inherit the traditions of their ancestors all the while desperately trying to destroy them. Devoid of hope, of purpose, and of human connection the youth of the day get their kicks vicariously, so busy sharing their experiences online that reality has become an obsolete concept and the physical sensation of violence the only remaining truth. We don’t move forward in this dance, comments the lady currently being waltzed by a charming lost soul. Don’t worry, he says, that’s not a bad thing. Indeed, Out There, the first independent feature film from director Takehiro Ito exists in a fixed yet liminal space, here and not there as its protagonist finds himself without the proper place to be. Conceived as a way of salvaging some of the material collated for a documentary on the late Taiwanese director Edward Yang, Out There takes more of its cues from Tsai Ming-liang or even Lav Diaz in its preoccupation with the intersection between time, existence, and place. If that all sounds to weighty, there’s a little whimsy in here too, but the intent is a serious one as nationhood (or the lack of it), drifting cultures, love and history all conspire to confuse and distract the course of a young man in search of an identity which is entirely his own.

We don’t move forward in this dance, comments the lady currently being waltzed by a charming lost soul. Don’t worry, he says, that’s not a bad thing. Indeed, Out There, the first independent feature film from director Takehiro Ito exists in a fixed yet liminal space, here and not there as its protagonist finds himself without the proper place to be. Conceived as a way of salvaging some of the material collated for a documentary on the late Taiwanese director Edward Yang, Out There takes more of its cues from Tsai Ming-liang or even Lav Diaz in its preoccupation with the intersection between time, existence, and place. If that all sounds to weighty, there’s a little whimsy in here too, but the intent is a serious one as nationhood (or the lack of it), drifting cultures, love and history all conspire to confuse and distract the course of a young man in search of an identity which is entirely his own.